Memento Mortensen

By:

March 18, 2011

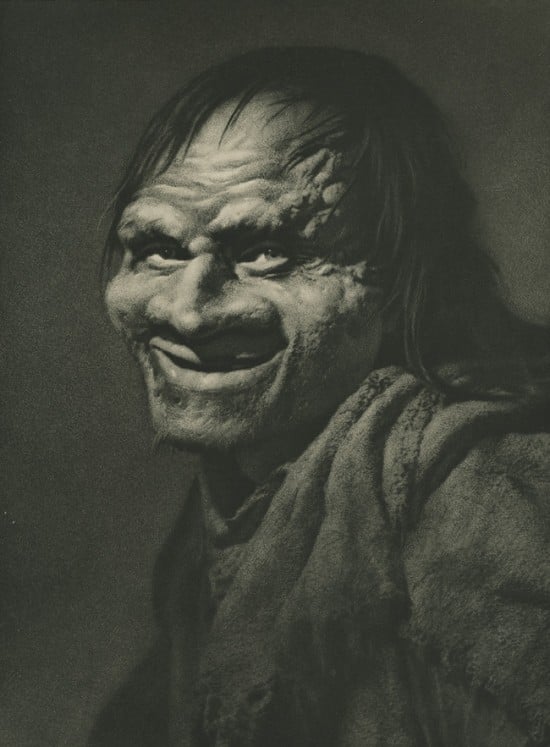

The all-but-forgotten early twentieth-century photographer William Mortensen (1897–1965) gets another look at 50Watts, the new project of A Journey Round My Skull blogger Will Schofield. In a guest post called Monsters and Madonnas: Looking at William Mortensen, Cary Loren of the fascinating Detroit-area book shop The Book Beat discusses the heavily-worked, romantic grotesques that make up Mortensen’s most compelling work.

Mortensen saw duality at work in the process of all artistic production. The technical, mechanical, and scientific were entwined yet at odds within the creative impulse. This duality was even more concentrated in photography, a process obsessed by the technical and mechanical “Monster.” Mortensen saw the scientific “Threat of the Machine” — The Monster — standing beside its ancient antithesis, The Madonna — “a symbol of fruitfulness and growth, of life and creative energy.”

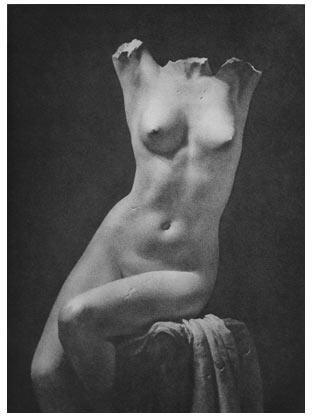

Back in 2001, The Scream Online posted a thorough feature on Mortensen, focusing on the photographer’s nudes — like this astonishing image, a heavily-worked study of the photographer’s wife, Myrdith Monaghan:

Mortensen physically and chemically ravaged his image, carving away the arms and head with solution of permanganate and scarring the emulsion with a razor to turn his model’s supple living body into a broken classical statue. It’s a vivid, provoking meditation on the nature of art, the eye, and the violence of history.

Working in Hollywood, Mortensen partook of the movies’ heavy blending of sex, sentiment, and technical expertise. His pictorialist proclivities were deprecated by the modernist photographers that followed him — particularly by Ansel Adams, who called him the anti-Christ. Adams’ sharp-focus studies of natural form were at odds with Mortensen’s turbid romantic vision. Of course, Adams’ images are every bit as figured as Mortensen’s; his vast depths of field in particular, contrived by precision optics and far beyond the capacity of the human eye, fashion invisible, valley-wide crystal palaces vaguely totalitarian in their assumption of infinitude.

Although they’re sought after by collectors, Mortensen’s books and images remain a backwater compared to the tide of Ansel Adams volumes, calendars, and tote bags. And yet today we take the plastic nature of the photographic image for granted; late in the Photoshop era, Mortensen’s pictures may yet find a receptive audience.