Pixel Sworcery

By:

April 8, 2010

In the mainstream game industry, studios compete to develop ever-more uncanny cinematic cut scenes and spectacular splatter effects. But in the world of indie game developers, different expectations apply. The “art games” created by such independent designers often take aim at the concept of gaming itself, seeking to transcend the borders of skill and simulated violence. To make a game that poses questions of the human condition is one thing; making such a game playable and entertaining is another. That’s what’s so enticing about the “painterly pixel world” that comes alive in Sword and Sworcery, the forthcoming iPhone game by the Canadian artist Craig Adams (aka Superbrothers), in collaboration with audio designer and composer Jim Guthrie and independent game studio Capy.

S:S&S EP: “sworcery” @ GDC 2010 from Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery on Vimeo.

With its subtle palette, enigmatic characters, and gameplay that takes full advantage of the iPhone’s unique capabilities, Sword and Sworcery feels utterly up-to-date. And yet in one quite obvious respect, it’s a conscious throwback to a bygone era. Like much of Craig Adams’ work, Sworcery’s graphic signature is the pixel — an artistic medium with a longer pedigree than it’s typically given credit for.

While pointilism and the pixel share certain salient features — and use the same neurological machinery to achieve realistic effects — the pixel evokes its own wealth of specific (and obvious) cultural markers.

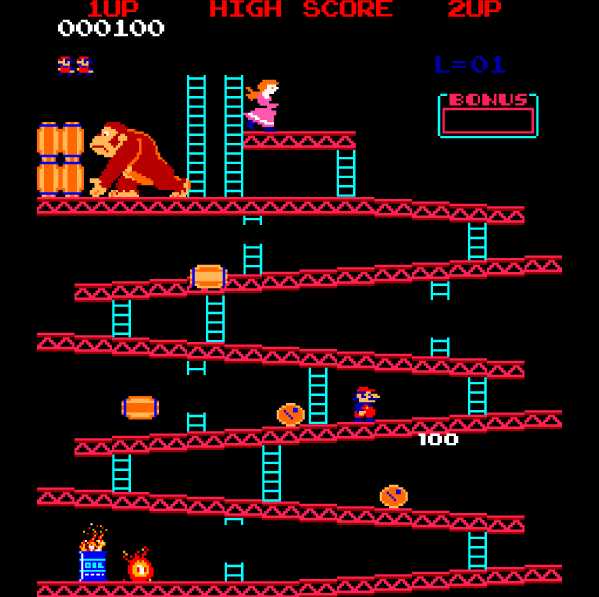

The medium of 8-bit graphics in which the first console video games were rendered, the pixel is an artistic medium to which members of the Reconstructionist generation (born 1964-1973) are especially sensitive. In fact, it’s a member of that generation: the term “pixel,” a contraction of “picture” and “element,” first appeared in 1964 in articles published by Jet Propulson Lab scientist Fred Billingsley, who worked on digital imaging technology for NASA’s Mariner missions to Mars. But Donkey Kong and Pole Position aren’t the pixel’s only references.

The ubiquitous Lego paved the way for the pixel. The blocky, iterative quality of Lego’s visual style, the discrete nature of the blocks — perhaps these markers helped to lay down pixel-friendly pathways in the brains of those born after the mid-1960s. But something else — something structural — unites Lego and the pixel: both are “universal” systems. They’re extensible; and in each case, the one implies the many, the all. Building with Lego blocks is a little bit like programming; by playing with the lock-together blocks, you join a virtual community — one of rich invention and endless creativity, and yet beholden to a system, a godlike corporate entity.

Sword and Sworcery is hardly the only art game to play with pixels. Jason Rohrer’s highly influential game Passage depicts a hyperpixelate world, where bright, blocky characters play out their lives quixotically searching for meaning in a world that is a supersaturated, ever-shifting tapestry of pixels.

Passage’s sprite sheet (a file that serves as a resource for character animation) shows the utter simplicity of Rohrer’s characters. And yet they seem to have a rich life — for in fact it’s our own rich life that we see reflected through their radically particulate avatars. Rohrer’s next game, Sleep is Death, is billed as a “storytelling game,” in which two players vie to create and fracture a tale of their own telling. Its gameplay promises to be unique, even transformative. But as in his earlier work, Rohrer will rely on the rich, dazzling, deceptively simple pixel as the foundation of his game’s graphic design.

The pixel-born characters of games, typically called sprites, evoke a chiming association with another world — the realm of faerie. Pixies — wee, uncanny spirits, perfectly wild, which haunt the broken world of folklore — seem to have lent not only their name, but a bit of their glamor, to the picture elements of electronic imagery. What is the pixel? It’s a place, a discrete spot on a screen. It’s a particle, a quantum entity capable of subtle phase-shifts and transformations. The pixel turned the optical game of pointilism into a kind of visual particle physics. It’s also a fey, winking ghost in the machine — beckoning us to partake of its magic — reminding us that cyberspace, too, is a faerie realm.

Despite advancing technology and the dizzying logic of Moore’s implacable law, the pixel’s power to fascinate remains undiminished.