Simulacra (5)

By:

May 5, 2020

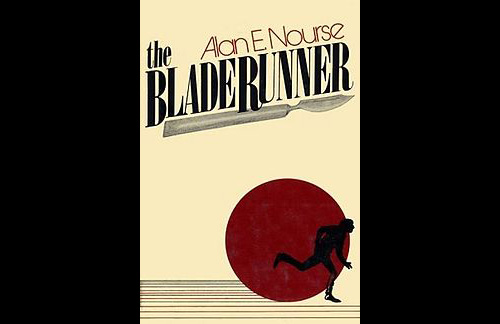

You could be forgiven for thinking the dominant narrative of 2020 is Contagion, Outbreak, or 12 Monkeys. Or Richard Preston’s The Hot Zone. Or even (or especially) John M. Barry’s The Great Influenza, about the 1918 flu. But a closer, and more uncanny, parallax is described in The Bladerunner.

No, not that one.

And not the contributions of William S. Burroughs, either. The text under consideration is The Bladerunner by Alan E. Nourse, a 1974 novel set in a near-future medical dystopia, a place and time otherwise known as “right now”.

[Warning: spoilers ahead.]

Sharing nothing with the Ridley Scott movie except the name (and that through a rather accidental alliteration), The Bladerunner has much more in common with real New York in 2020 than imagined Los Angeles in 2019.

In Nourse’s New York, there is vast inequality. The poor (and notably, uninsured), live literally in the lower city, nearer to the ground. Accessed by a series of soaring Robert Moses-like arterial overpasses and cloverleafs, and a fleet of hover taxis, the upper city hosts the privileged classes, as well as their civilizing institutions, such as universities, city halls, theaters, and hospitals. Further afield are housing projects as well as more affluent suburbs, reached by private ‘copters. In the upper city live and work the doctors, nurses, and various government functionaries. In the lower city live the poor, the gig workers, the unemployed, the precariot — people like Billy Gimp.

Billy is a bladerunner, one of the bike-and-pedestrian messengers who inhabit a grey, and sometimes black, legal area, who interface with illegal bodegas and fences providing antibiotics, syringes, gauze, anesthetic, and everything else that might be needed for DIY operations at home, including the eponymous blades. Billy is an essential, if essentially illegal, worker.

Because what really divides and defines this society is access to health care. If you have enough money, you have insurance and can be treated for any malady. If you don’t, you have the following unappealing options: black market operations, refuse all vaccines — indeed all treatment — for everything (there’s a cult for that), or go to any hospital and be treated — but also be sterilized, so as to prevent, you know, more of your lot. Most, if they could manage it, tried the black market.

And who worked this black market? Many of the same doctors employed by the hospitals, who didn’t believe in policy decisions that restricted health care to the wealthy and forced sterilization on everyone else. And Billy is more than just a ‘runner; he assists his doctors with procedures and is gaining a serious education in practical surgery, and dreams of someday getting a real medical license, although there’s absolutely no avenue by which he could pursue this.

Into this society comes a pandemic.

It moves in subtly at first. It’s winter, and people start experiencing seasonal colds and flu. The symptoms are the usual suspects, manageable, and it’s easy for the poor to avoid either the nuclear hospital option or the black market. After all, it wasn’t too bad and cleared up in about a week.

But Billy, and the doctors and some very few others, have noticed a much worse infection starting to make the rounds. In contrast to the cold, this one comes on strong, collapsing the lungs, stressing the heart, and taking its victims out in just a day or two. It’s brand new. There is no cure, and there’s effective treatment only if it’s caught right at the beginning; once the serious symptoms set in it’s too late. A few cases at first, but then more. And more.

It turns out that the seasonal cold was just the preliminary, highly-contagious first phase of the novel virus. There are thousands, possibly millions, of asymptomatic (actually pre-symptomatic) spreaders. And it’s about to explode.

The exponential projections don’t look survivable, for either individual victims or society at large. The society has a prophylactic anti-viral regimen, and fancy ventilators, but treatment only works if administered before the second-phase, fatal symptoms hit. This means they’re going to have to reach everybody, insured or not (especially not), and fast. But the poor won’t risk certain sterilization, and besides, they don’t believe that the cold is really the first phase of the novel virus. The cultists refuse to believe that they could be vectors. And the rich, the only ones with access to the anti-virals, will be taken out anyway by the sheer scale of the outbreak as the curve arcs up and the hospitals become overwhelmed.

There’s no technological solution, in other words. It is as if Rilke, writ large, is saying to civilization in general: you must change your life.

Meanwhile the top brass is on to the illegal moonlighting of the doctors. The anti-vaxxer protests are becoming bigger, and more violent. Billy has been arrested, and then released, but tracked by the very latest hi-tech surveillance devices — and he’s not feeling too good. Basically, to defeat this virus, they’ve got to solve all their problems of structural, economic, technological, and tiered-biological inequality. And they’ve got to do it in about a week.

Can they do it? Will they make it? I mean, how…? I won’t tell you how it plays out, except to reflect that dystopias are so-called for a reason. Throughout his medical-horror adventure tale, Nourse offers lessons from 1974’s imagined future, lessons that in 2020’s lived reality we would do well to heed.

It would make a great movie.

Alan E. Nourse: The Bladerunner; buy the e-book

John M. Barry: The Great Influenza

William S. Burroughs: Blade Runner (a movie) (a book)

Abraham Reisman: Why is Blade Runner the Title of Blade Runner?

Adi Robertson: How Blade Runner got its name from a dystopian book about health care

Isaac L. Wheeler: The Story Behind Blade Runner’s Title

Ridley Scott: Blade Runner (1982 film)

Philip K. Dick: Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?