RADIUM AGE ART (1901)

By:

January 12, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

Please note that in my periodization schema, the years 1900–1903 are an interregnum of sorts, during which the seeds of science fiction’s Radium Age were planted. Thus, while artwork from this year (1901) may hint at the Radium Age proto-sf adjacent artwork to come, it may not exactly be something I’d want to describe with certainty as “Radium Age art.”

1901 is considered the final year of the Aesthetic movement.

A showing of 71 Vincent van Gogh paintings in Paris, 10 years after his death, creates a sensation.

Picasso, an avid admirer of Gauguin, whose works he first encountered while visiting Paris in 1901, will enthusiastically embrace Symbolism during his formative years in Barcelona. (Picasso’s first exhibit — at age 19 — in Paris this year.)

While the word expressionist was used in the modern sense as early as 1850, its origin is sometimes traced to paintings exhibited in 1901 in Paris by the otherwise obscure artist Julien–Auguste Hervé; he called his exhibit Expressionismes.

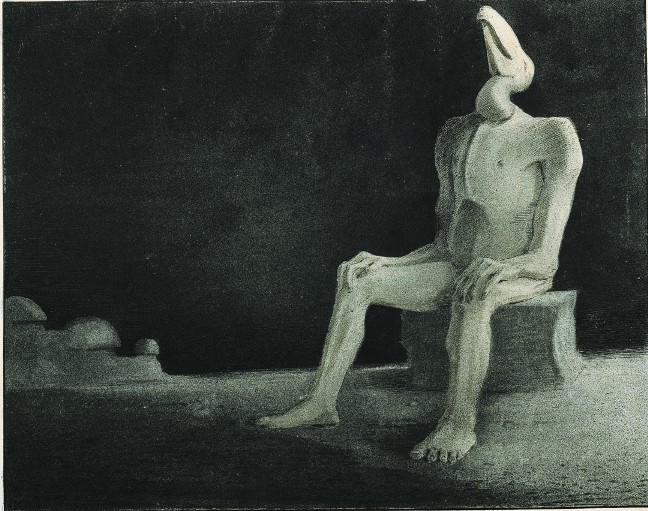

The Swiss Symbolist Arnold Böcklin dies in 1901. His reputation declines rapidly; however, his work was a significant influence on Giorgio de Chirico – who said “Each of Böcklin’s works is a shock.” Later he’d be admired by Surrealist painters such as Max Ernst and Salvador Dalí.

At the age of 35, Kandinsky quits his painting class at the Munich Academy and founds the Phalanx, a group whose purpoise is to organize exhibits informing the public about the “art of tomorrow.”

Oliver Lodge, the eminent British physicist involved in the development of, and holder of key patents for, radio, becomes president of the London-based Society for Psychical Research from 1901 to 1903. (William James was president in 1894–1895; Henri Bergson would become president in 1913; Camille Flammarion in 1923. The physicist William Crookes, president from 1896–1899, invented the Crookes tube — via which cathode rays (streams of negatively charged particles later named electrons) were first discovered. At the time, atoms were the smallest particles known and were believed to be indivisible, the electron was unknown, and what carried electric currents was a mystery. Electrons were the first subatomic particles to be discovered. In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen would discover X-rays emanating from Crookes tubes.) Scientific work on electromagnetic radiation convinced Lodge that an ether existed and that it filled the entire universe. Lodge came to believe that the spirit world existed in the ether.

Marconi receives the first trans-Atlantic radio signal.

Death of Queen Victoria.

See: RADIUM AGE: 1901

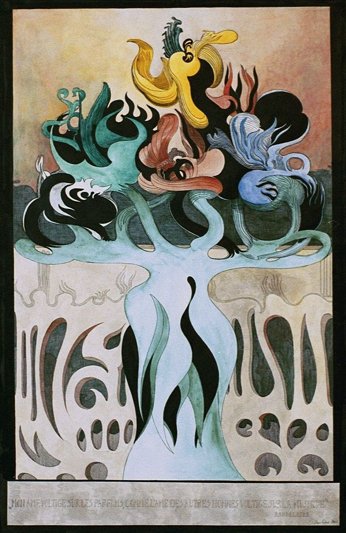

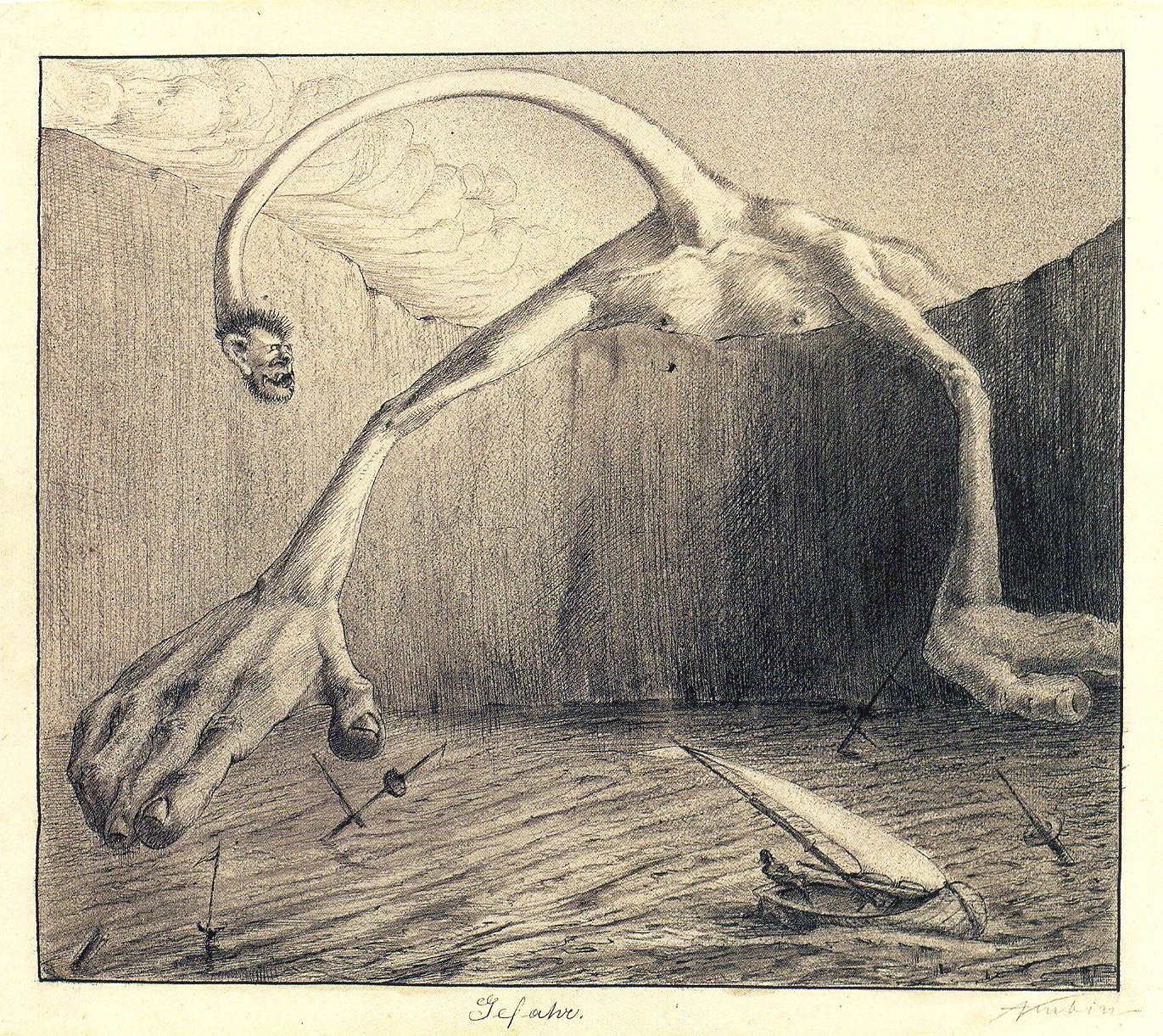

For fifteen years Vrubel produced works inspired by Lermontov’s The Demon. In Vrúbel’s work the demon evolves from a being of superhuman beauty to a crushed and desperate being. Dubbed the Russian Cézanne by Naum Gabo, Vrubel’s work influenced Malevich and Kandinsky.

Also see Lund’s “Flower of the Night” (1898).

Olbrich was a central figure in the revolutionary modern art movements that took place in Vienna at the end of the 19th century. He was a founding member of the Vienna Secession in 1897. He exhibited this anthropomorphic and now iconic design for a candlestick at the Saint Louis World’s Fair in 1904.

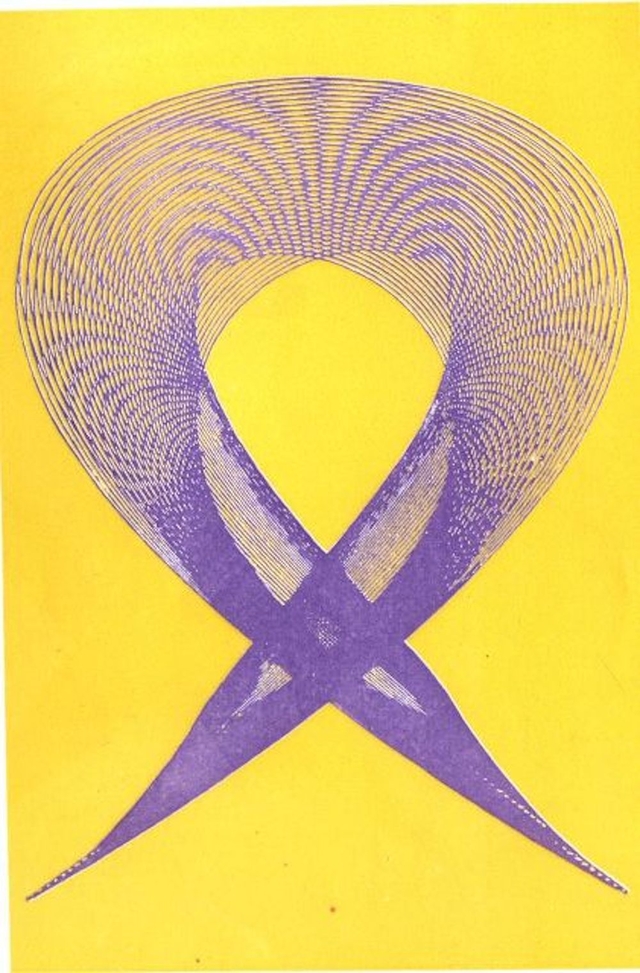

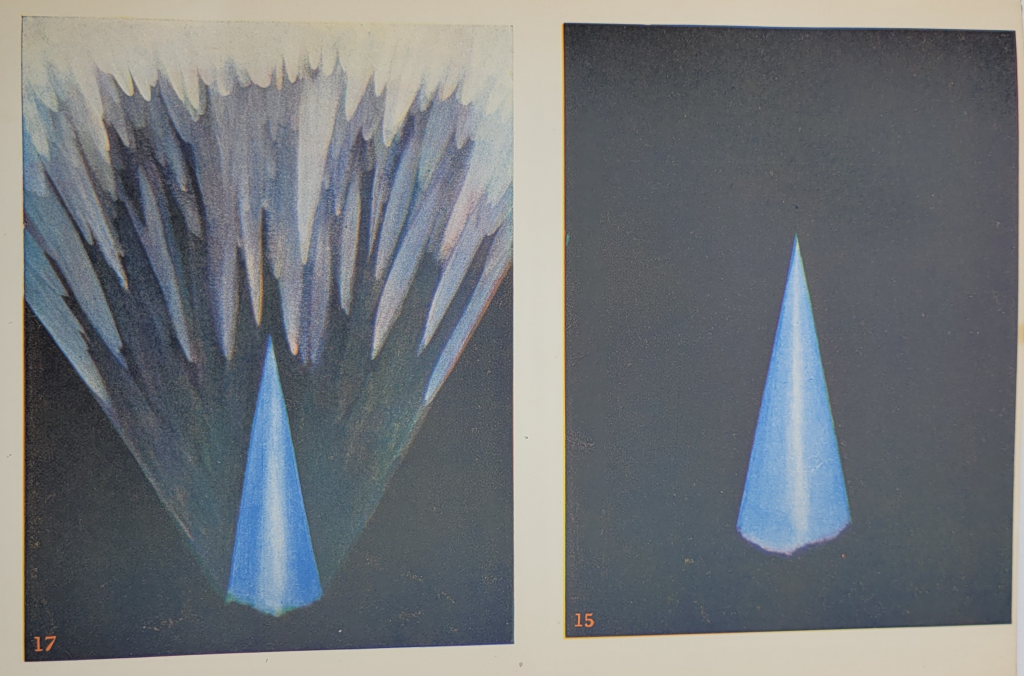

As an example of the supersensible vibrations of the electromagnetic spectrum, X rays offered contemporary occultists a scientific rationale for phenomena such as clairvoyance as well as telepathy. Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater cited x rays in the introduction to Thought Forms (1901), in which they focused on vibrations as the means for transferring thought patterns from one individual to another. (Leadbeater had dealt more extensively with x rays in his 1899 Clairvoyance, which was translated into French and published in Paris in 1910. See 1910.)

Besant and Leadbeater claim, in the introduction to Thought-Forms: A Record of Clairvoyant Investigation, that Curie’s discovery of radium and Röntgen’s X-ray photos (which had caused a global sensation in 1896) had “revolutionized the concept of matter and are leading science into the astral world.”

Theosophists believe there to be several occult “planes of existence” (the astral plane is only one of them!), each characterized by particular rates of vibrational energy. Thoughts and feelings, too, create vibrations — we read in Besant and Leadbeater’s Thought-Forms. Though imperceptible to the untrained eye or ear, these vibrations manifest as various shapes, colors, and sounds that can be “read” — surfaced and dimensionalized — by the initiated. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again; this is also what Saussure claims about signifiers.

Excerpts from Thought-Forms here.

Thought-Forms, even more so than other Theosophical texts (by Blavatsky, Annie Besant, and Rudolf Steiner in particular), circulated widely among artists in the first decades of the twentieth century. By the 1920s and ’30s, it was quite normal for those involved in artistic experimentation to also dabble in esoteric spirituality… which is not the same thing as saying that modern artists were spiritualists.

See more below about Theosophy.

NOTES ON THEOSOPHY AND MODERNIST ART

See this Wikipedia page.

Radical developments in science and technology helped pave the way for a perceptual and representational revolution in the arts during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The proto-sf that emerged during the era’s 1900–1935 Radium Age shared these same influences. I think these claims are uncontroversial. However, secularism and disenchantment were not the only options available. We’ve only recently begun to grapple with another key influence on the development of modernist art: Occult and spiritualist thought. Which also plays an important role in the genesis and evolution of Radium Age proto-sf.

In the years since LACMA’s 1986 exhibition The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890–1985, and the publication of the multi-authored exhibition catalog of that title, art museums and art historians have begun to pay attention to the connections between modernism, modernist abstraction in particular, and occult movements including but not limited to Theosophy. (The explosion of interest in Hilma af Klint’s work c. 2013–2014 helped in this regard.) Contra what we’d learned, for decades, from formalist historiography of modernist art, spiritual interests had something to do with the initial development of abstract art, during a time period that closely corresponds to science fiction’s 1900–1935 Radium Age.

In their introduction to Enchanted Modernities: Theosophy, the Arts and the American West (2019), Christopher M. Scheer, Sarah Victoria Turner, and James G. Mansell write of “the vast seam of research still to be done in order to fully chart and understand the widespread and manifold connections between modern art and Theosophy….”

The genius of Helena Blavatsky in pioneering Theosophy (the Theosophical Society was founded in 1875) — “a scientific religion and a religious science,” in the words of William Quan Judge (in 1893) — was to argue that scientific and spiritual approaches to developing knowledge and finding meaning were not actually at odds. Her major books supplemented scientific theories about creation, matter and energy with speculations about the origins of the cosmos drawn from ancient philosophies. Note that this was pre-Radium Age science. Thomas Edison joined the Theosophical Society in 1878, at which point Blavatsky began to connect occultism with the scientific phenomena of electromagnetism, color and sound waves, and telegraphy.

Spiritual but unhappy with organized religion? Enquiring but unhappy with the cold empiricism of science? In her texts Isis Unveiled (1877) and The Secret Doctrine (1888), she argued persuasively that science and religion alike were remnants — fragmentary and corrupted remnants — of a lost knowledge of the truth of existence. The modern person’s experience of spiritual belief and scientific method alike offered glimpses, but nothing more than glimpses, of this lost “Divine Wisdom.”

Gauri Viswanathan writes that Theosophy’s phenomenal growth in the late 19th century was a function of its location in the era’s religion–science debate. Blavatsky wrote against the current trends of materialism and science “in order to stake a claim for the prevalence of spirit and consciousness.” At the same time, however, she railed against religious orthodoxies. Theosophy itself was not a religion, its adherents (like C.W. Leadbeater and Annie Besant) insisted; it was the truth behind the world’s great religions; and it was a science too. Signifiers of the lost wisdom could be surfaced from Eastern religions, as well as from occult and esoteric traditions in Western culture. “Blavatsky steered a middle course between the polarities of science and religion — one that preserved science’s quest for knowledge while insisting that true scientific understanding extended beyond matter to include supersensible phenomena,” which is to say those phenomena of nature that are not reducible to scientific laws not can be apprehended by the immediate senses. — Gauri Viswanathan

Blavatsky, who as a teenager made a study of Rosicrucianism, Freemasonry, and Hermeticism, among other esoteric philosophies, “interrupted the construction of world religions by critiquing orthodox systems of thought as corruptions of religion’s true nature, as a corrective to which she resurrected the heterodoxies that had either been banished or marginalized by mainstream religion.” — Gauri Viswanathans “The World of Helena P. Blavatsky” (in Enchanted Modernities: Theosophy, the Arts and the American West). Blavatsky’s disciple Annie Besant argues in her 1901 book Esoteric Christianity that the era’ agnosticism was not so much a rejection of faith and morality as a search for the hidden meanings of Christianity. Blavatsky sought to identify a core knowledge of esoteric truth — running as a common thread through all world religions — which she called “Theosophy.”

“What united artists interested in Theosophical ideas was a belief in occult forces at work in the natural world that, although they might not be immediately apparent to the spiritually untrained observer, could be revealed in, or through, music or art.” — from the introduction to Enchanted Modernities: Theosophy, the Arts and the American West.

They were attracted by the Theosophical concept of a “universal harmony underlying the apparent chaos” of the physical world. — Ann Davis, “Theosophy” entry, Grove Art Online. In an 1875 letter quoted in Gauri Viswanathan’s essay, we discover Blavatsky talking about the very shape of the universe: Without the structural underpinnings revealed by Spiritualism (confusingly, she calls the structural underpinnings themselves “Spiritualism”), she writes, “the Macrocosmos would soon go topsy-turvy, as a thing that popped out without any fundamental basis under it — a result without any reasonable cause for it — or a frolic of blind force and matter…” Fascinating!

Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society “opened doors for the exploration of psychic and spiritual states that defied rational, positivist comprehension and upheld the value of the creative imagination.” (Gauri Viswanathan)

Occult notions of “astral sight” or “four-dimensional vision” — which surpass the merely material, illusory world of the senses and give access to permanent transcendental realities — were now, occultists and psychical researchers exulted, scientifically proven.

Besant and Leadbeater encouraged visual artists to aid the process of communal spiritual evolution by attempting to depict, no matter how imperfectly, such imperceptible vibrations. In doing so, artists would act as a conduit conveying spiritual insight to the viewer.

Theosophy, Gauri Viswanathan writes, contains insights and inspiration that helped artists “move far beyond the limiting Kantian categories of time, space and causality. From such images they developed non-representational art forms to convey spiritual and psychic realities that remained unseen and unknown.” Blavatasky’s “greatest influence may have been on art rather than the history of ideas…”

NOTES ON ANTHROPOSOPHY

Rudolph Steiner during this period begins lecturing about what will become anthroposophy — a new religious movement that aims to study the spiritual world with comparable precision and clarity to that obtained by scientists investigating the physical world. Published in 1901: Steiner’s Mysticism at the Dawn of the Modern Age.

In his unfinished autobiography, Steiner would relate that even as a child, he’d felt “that one must carry the knowledge of the spiritual world within oneself after the fashion of geometry … [for here] one is permitted to know something which the mind alone, through its own power, experiences. In this feeling I found the justification for the spiritual world that I experienced … I confirmed for myself by means of geometry the feeling that I must speak of a world ‘which is not seen’.”

Anthroposophy is an occult science built on an assumption of exact parallelism between the microcosm and the macrocosm.

Also…

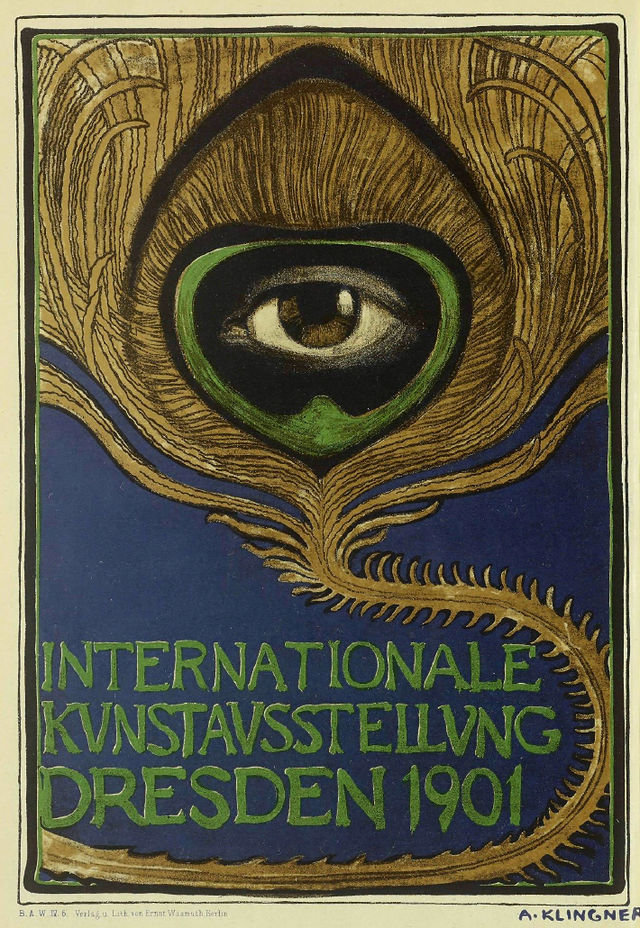

Edel was a Berlin-based painter and illustrator known for his distinctive poster art.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.