RADIUM AGE ART (1922)

By:

August 15, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

In a 1922 letter, Mondrian insists that his abstract “Neoplastic” work “is purely a theosophical art.” Although affected by Cubism, Mondrian’s thinking predated his encounter with Cubism, and is ultimately rooted in esoteric doctrines of mathematics. Mondrian was painting semiotic graphs — attempting to express general, not specific, truths.

In Japan, Harue Koga assists in the formation of the avant-garde art group “Action.”

The Grupo Montparnasse was an organization of Chilean artists who had joined the gathering of great artists in the Montparnasse Quarter of Paris, France, in the early part of the 20th century. Founding members, Luis Vargas Rosas and Camilo Mori among others, exhibit in the Salon d’Automne of 1920 in Paris where they meet Juan Gris, Pablo Picasso and other artists experimenting in the new trends of the time like cubism and expressionism. The group’s first exhibition was organized by Luis Vargas Rosas in Santiago in 1923.

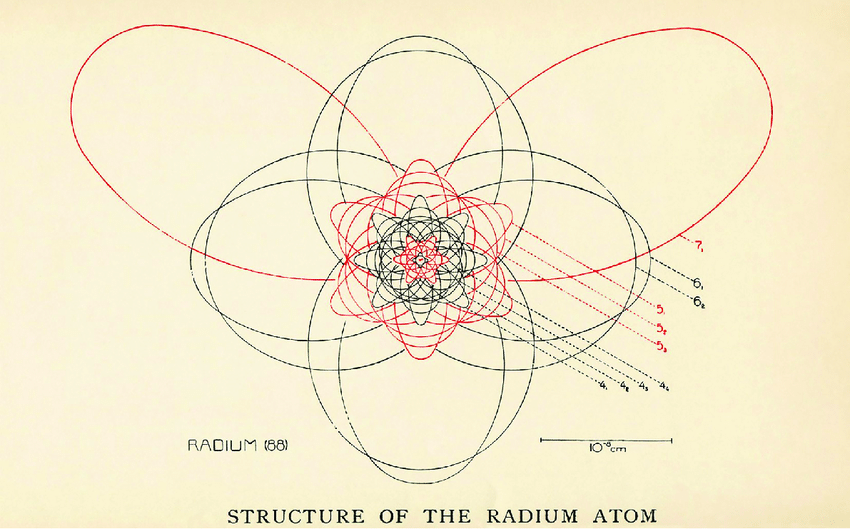

Bohr wins Nobel for investigations into atomic structure and radiation.

The world’s first regular wireless broadcasts for entertainment begin transmission from a hut at the Marconi Company laboratories in England.

Mussolini forms Fascist government.

Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” Joyce’s Ulysses. See Susan Sutliff Brown’s 1987 thesis “The Geometry of James Joyce’s Ulysses: From Pythagoras to Poincaré: Joyce’s Use of Geometry for Structure, Metaphor, and Theme.” Excerpt:

Throughout Ulysses Joyce weaves the image of parallel lines first in Euclidean and then in non-Euclidean geometry, of a persecuted visionary who momentarily transcends three dimensional space (Bloom in “Circe”), and of a protagonist whose most profound philosophical debate is linked to new theories of vision and visual perception when he “sees flat” and “thinks distance.” Joyce critics, however, have failed to identify these as the most significant and familiar images of the post -Newtonian version of the physics revolution; thus, they have failed to comprehend the scientific and epistemological context in which Ulysses was written and to recognize Joyce’s scientific/metaphysical setting for the events of June 16, 1904. Once Joyce’s geometric images are identified as references to the post -Newtonian revolution in physics, the themes of Ulysses can be evaluated in their proper historical context.

Carnap seeks to provide a logical basis for a theory of space and time in physics in his doctoral thesis Der Raum (Space).

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1922.

Speaking of catastrophe, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage (reissued by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series) appears in 1922.

Witkiewicz was a Polish writer, painter, philosopher, theorist, playwright, novelist, and photographer. He committed Suicide just after the Nazi invasion of his country when he learned that Soviet armies had attacked from the east, the direction in which he was fleeing.

Much of his work, some eerily prophetic, deals darkly and humorously with the theme of a conservative world suddenly subjected to change, the clash of cultures, future totalitarianisms and apocalypse. Set in the twenty-first century, his 1930 novel Nienasycenie shows a fractured, ersatz West, a consumer society subject to a growing appetite for novelty, being taken over by Chinese Communists and Eastern mysticism, whose purveyors also provide happy pills.

Crotti and his wife Suzanne Duchamp developed Tabu, an offshoot of Dada distinguished, according to The New York Times critic Holland Cotter, “by its rejection of the negative, anti-art aspects of the original.”

While the style proved short-lived, Nocturne (1922) — three large, overlapping spheres punctuated by smaller black and white circles — is a particularly fine example, its planetary forms representing the birth and death of the universe, a subject that engrossed Crotti.

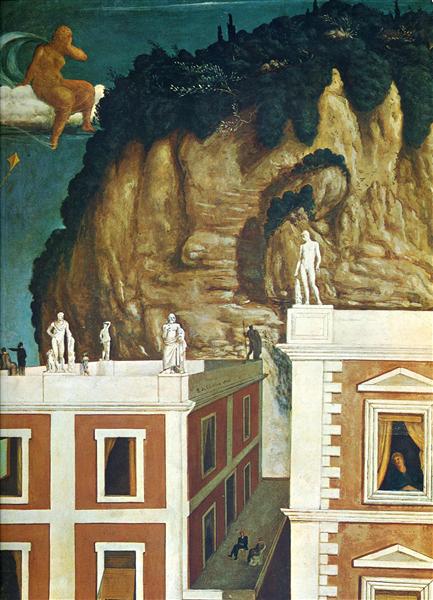

Completed in 1922 as de Chirico was in transition from the Metaphysical style of his earlier works to the neoclassicism he essayed in the 1920s.

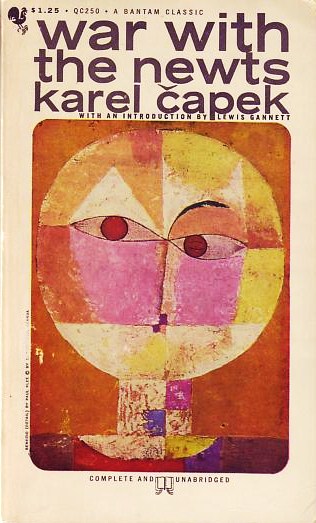

See below for an example of this artwork used as an sf cover illustration.

Léger’s boldly simplified treatment of modern subject matter has caused him to be regarded as a forerunner of pop art. The Card Players (1917) marked the beginning of his “mechanical period”, during which the figures and objects he painted were characterized by sleekly rendered tubular and machine-like forms. The “mechanical” works he painted in the 1920s, in their formal clarity as well as in their subject matter — the mother and child, the female nude, figures in an ordered landscape — are typical of the postwar “return to order” in the arts. They also share traits with the work of Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant who together had founded Purism, a style intended as a rational, mathematically based corrective to the impulsiveness of cubism.

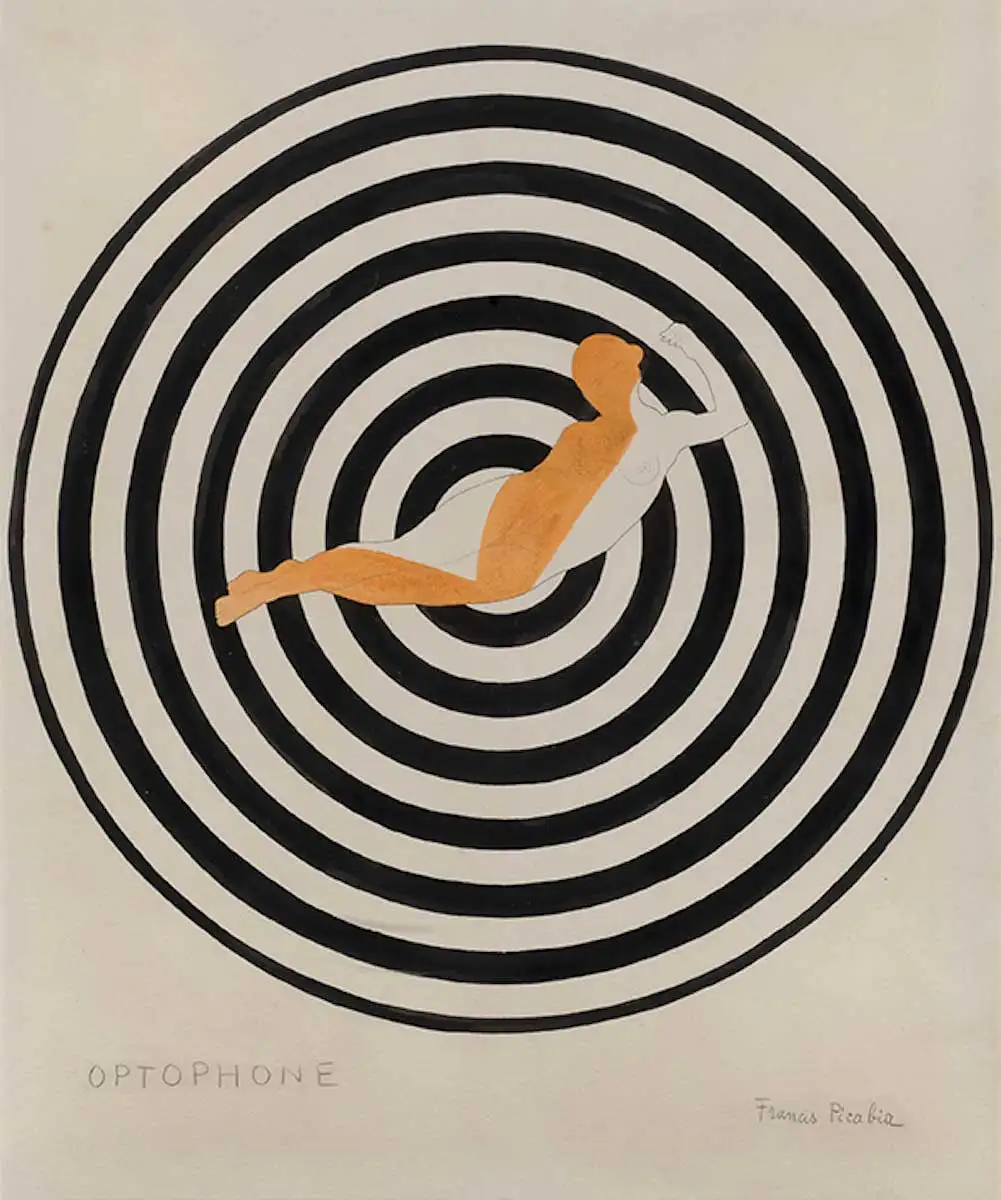

Picabia’s 1922 piece Optophone I represents the height of his Dada period. By the time he made this striking collage piece, the artist had befriended prominent figures like Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray. His art heavily featured elements of collage, mechanistic imagery, and Dadaist themes.

Demuth was a principal member of the Precisionist movement that emphasized sharp lines and clear geometric shapes. Pictured in the center of this composition is the steeple of the old Center Methodist Episcopal Church in Provincetown, Massachusetts (now the Provincetown Public Library).

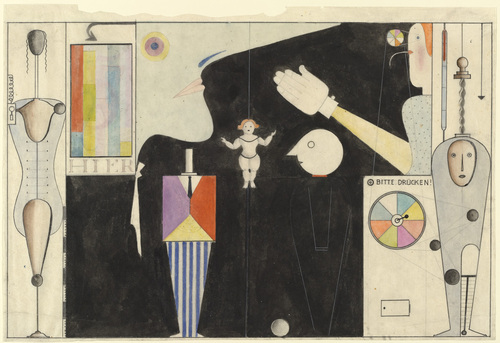

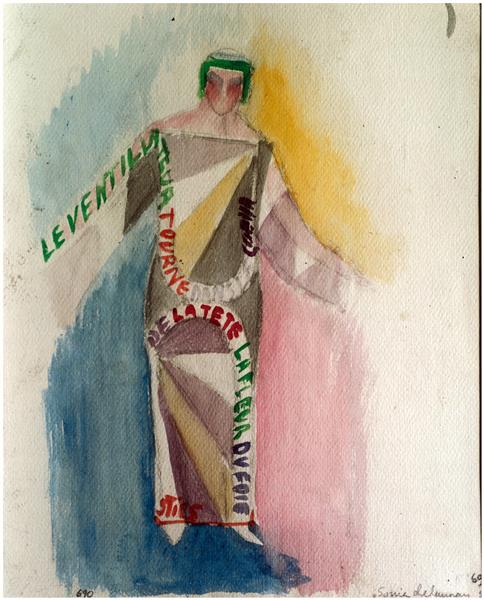

Schlemmer saw ballet and pantomime as free from the historical baggage of theatre and opera and thus able to present his ideas of choreographed geometry, man as dancer, transformed by costume, moving in space. His consideration of the human form (the abstract geometry of the body e.g. a cylinder for the neck, a circle for head and eyes) led to the all important costume design, to create what he called his ‘figurine’. The music followed and finally the dance movements were decided.

Schlemmer saw the modern world driven by two main currents, the mechanised (man as machine and the body as a mechanism) and the primordial impulses (the depths of creative urges). He claimed that the choreographed geometry of dance offered a synthesis, the Dionysian and emotional origins of dance, becomes strict and Apollonian in its final form.

The Belgian abstract painter Servranckx produces here, Pepe Karmel suggests in Abstract Art: A Global History, “a vivid impression of a mechanical universe” and “an ecstatic experience of sensory overload.”

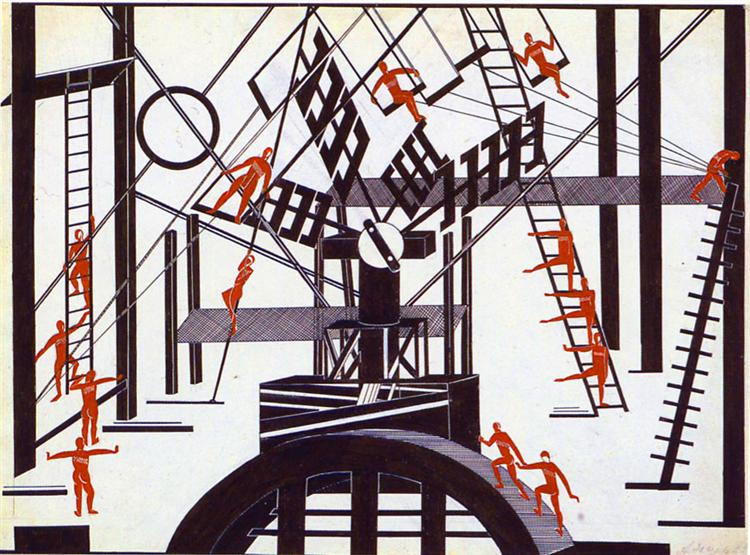

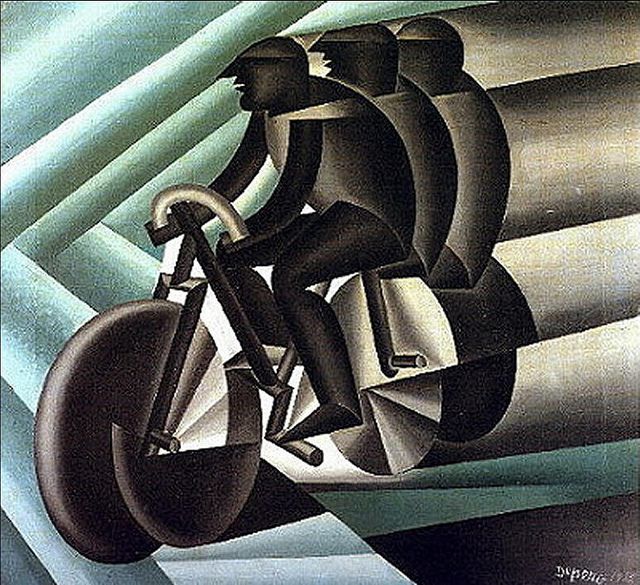

Following World War I, Futurism gained new members and assumed different formal qualities, including those of arte meccanica (machine aesthetics). While mechanized figures and forms had appeared earlier (in the art of Fortunato Depero, for example), Ivo Pannaggi and Vinicio Paladini articulated the principles of this idiom in their 1922 “Manifesto of Futurist Mechanical Art.” Enrico Prampolini also adopted a mechanical language at this time, and he subsequently expanded and signed the manifesto, publishing it in his journal Noi in 1923.

Pannaggi’s Speeding Train (1922) demonstrates the Futurists’ sustained interest in the locomotive as a symbol of modernity, motion, and the machine. Later, Pannaggi’s interest in machine aesthetics led him to integrate Constructivist elements such as beams, cubes, cylinders, and three-dimensional letters into his work.

From The Charnel House

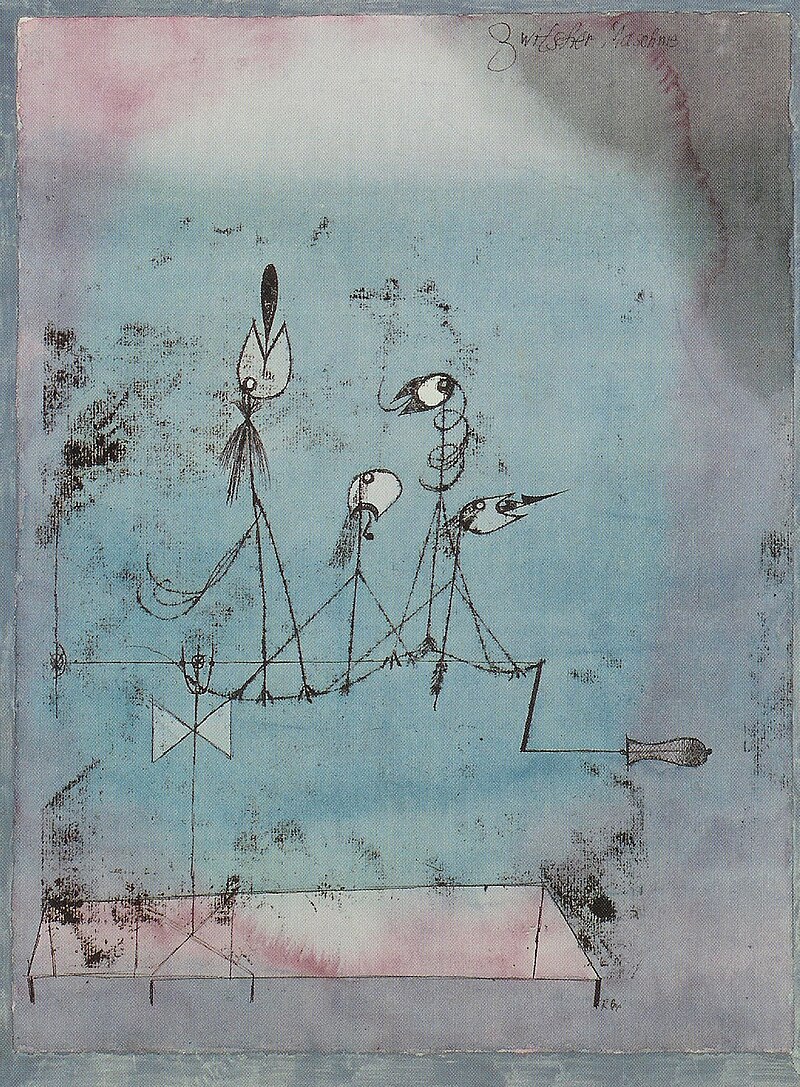

Like other artworks by Klee, it blends biology and machinery, depicting a loosely sketched group of birds on a wire or branch connected to a hand-crank. Interpretations of the work vary widely: it has been perceived as perhaps a nightmarish lure for the viewer or a depiction of the helplessness of the artist, but also perhaps as a triumph of nature over mechanical pursuits. Klee taught at the Bauhaus but he was indifferent to its machine aesthetic. This work seems like a parody of their celebrations of industrial machinery.

Originally displayed in Germany, the image was declared “degenerate art” by the Nazis in 1933.

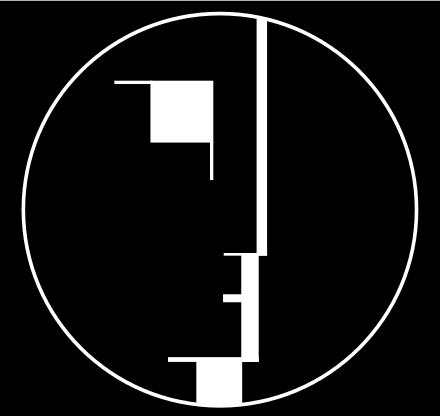

The flat geometric squares within the circle resemble a mask or the patches of a harlequin, hence the title’s reference to the artist-performer Senecio.

Man Ray made his “rayographs” without a camera by placing objects directly on a sheet of photosensitized paper and exposing it to light. Man Ray had photographed everyday objects before, but these unique, visionary images immediately put the photographer on par with the avant-garde painters of the day. Hovering between the abstract and the representational, the rayographs revealed a new way of seeing that delighted the Dadaist poets who championed his work, and that pointed the way to the dreamlike visions of the Surrealist writers and painters who followed.

Kandinsky’s “Small Worlds I” was used as the cover illustration for a 1963 edition of More Penguin Science Fiction edited by Brian W. Aldiss.

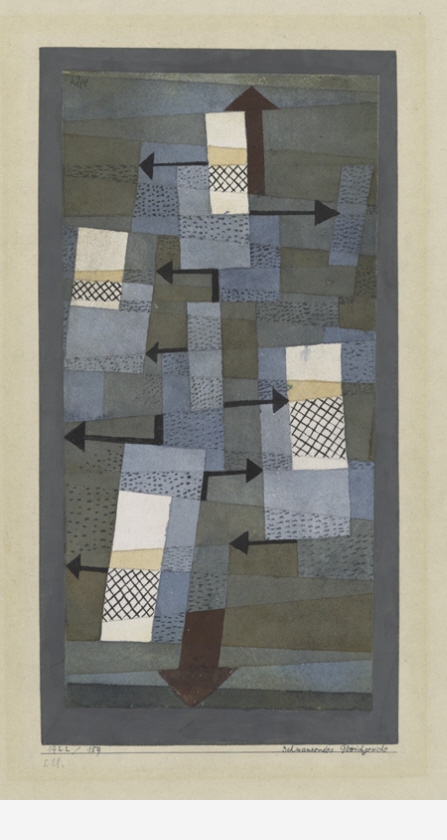

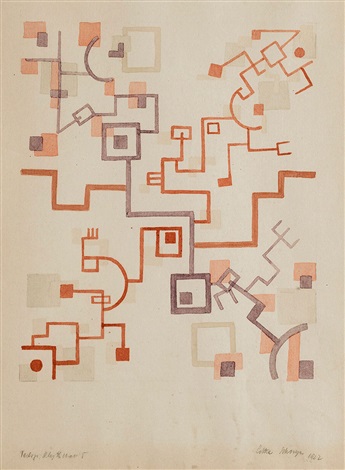

Netzwerk oder Geflecht (1922)

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Lightning at Sea (1922). One of a group of maritime paintings and pastels inspired by the artist’s 1922 visit to Maine. While many of these works are dominated by curving organic shapes, “Lightning at Sea” is unusually angular and schematic in its composition. The hard-edged linear quality of the lightning bolt and the sun rays at its center demonstrates O’Keeffe’s awareness, of and willingness to experiment with, modernist styles that were more geometric in nature.

Lajos Kassák was a Hungarian poet, novelist, painter, essayist, editor, and theoretician of the avant-garde. He believed that engineering exactness — the straight and curved lines of non-objective painting — prefigured a collective civilization and a collective culture. The elimination of spatial depth and the resulting unified picture plane reflected, Kassák claimed, the not-yet that awaited concretion, while the exclusion of figuration proclaimed the end of bourgeois particularism and instilled a desire for communal life. In his opinion, his work acted as a pledge for a better world. Its images of oneness contributed to the evolution of men and women into “collective individuals,” into subjects who identified with other members of all social classes and fully integrated into the masses.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.