RADIUM AGE ART (1915)

By:

June 6, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

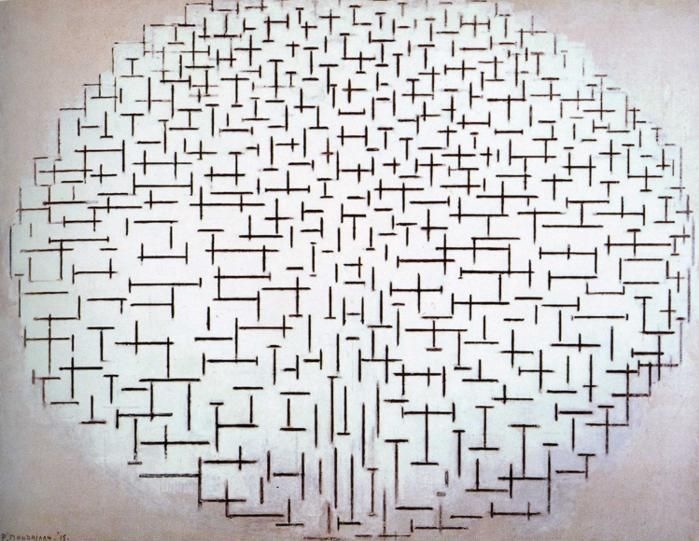

When some of Mondrian’s new compositions are exhibited in Amsterdam in 1915, they attract the attention of art critic (for a spiritualist publication) Theo van Doesburg. His review enthuses that Mondrian’s work creates an impression of “pure spirituality… the stillness of the soul.” The two begin to correspond — which in 1917 will lead to the formation of De Stijl.

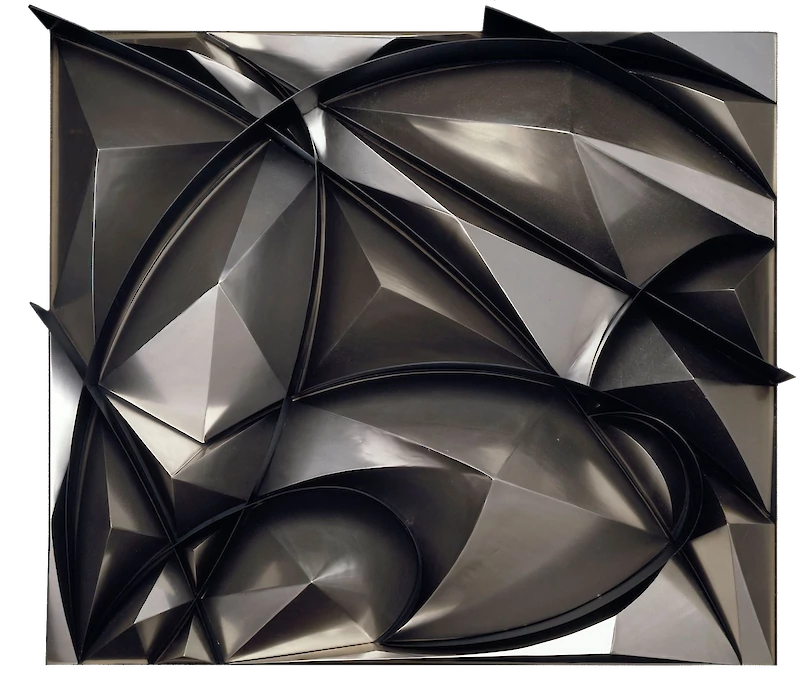

As Cubism and Futurism spread to Russia at the end of the 1910s, they were absorbed into the utopian spirit of the October Revolution, thus creating a new art movement known as Constructivism — which claimed that art should be “constructed” from modern industrial materials such as plastic, steel, and glass. The year 1915 is often given as the movement’s start date.

Rodchenko continues his artistic training at the Stroganov Institute in Moscow, where he creates his first abstract drawings, influenced by the Suprematism of Kazimir Malevich, in 1915. He used a compass and ruler in creating his paintings, with the goal of eliminating expressive brushwork.

Often credited with serving as the impetus for Constructivism is Vladimir Tatlin, who while studying in Paris in 1913, was influenced by Picasso’s geometric constructions. After migrating back to Russia, he, along with Antoine Pevsner and Naum Gabo, would publish the Realist Manifesto in 1920, which declared an admiration of machines and technology.

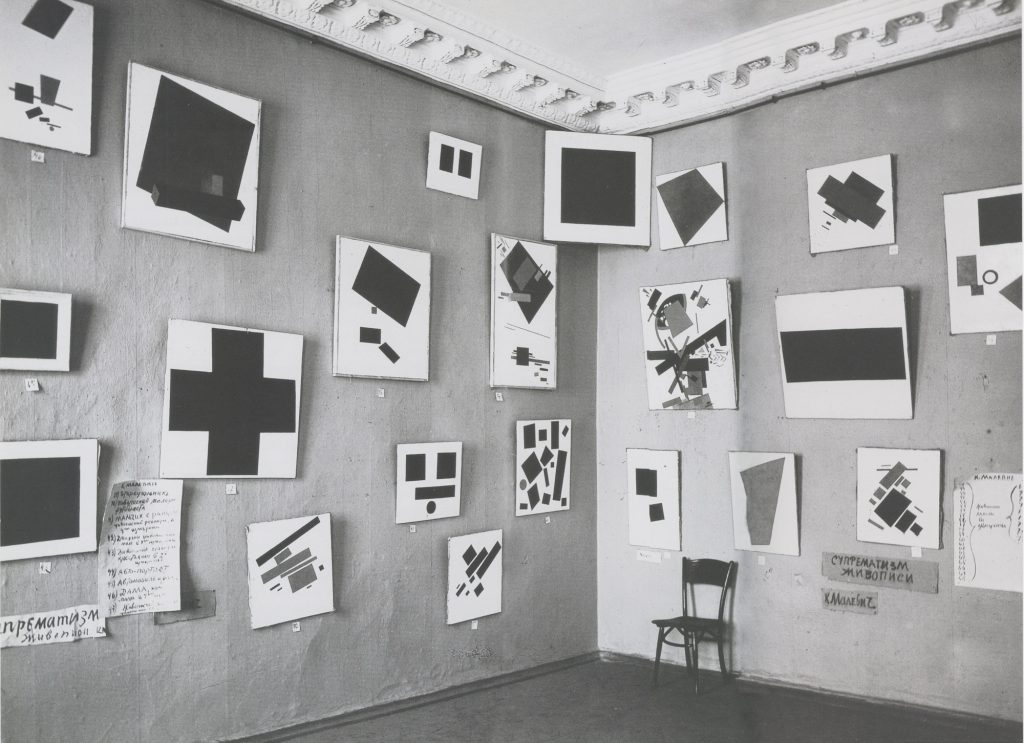

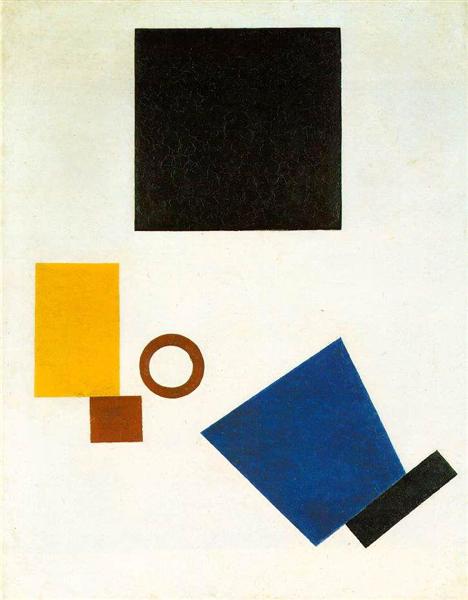

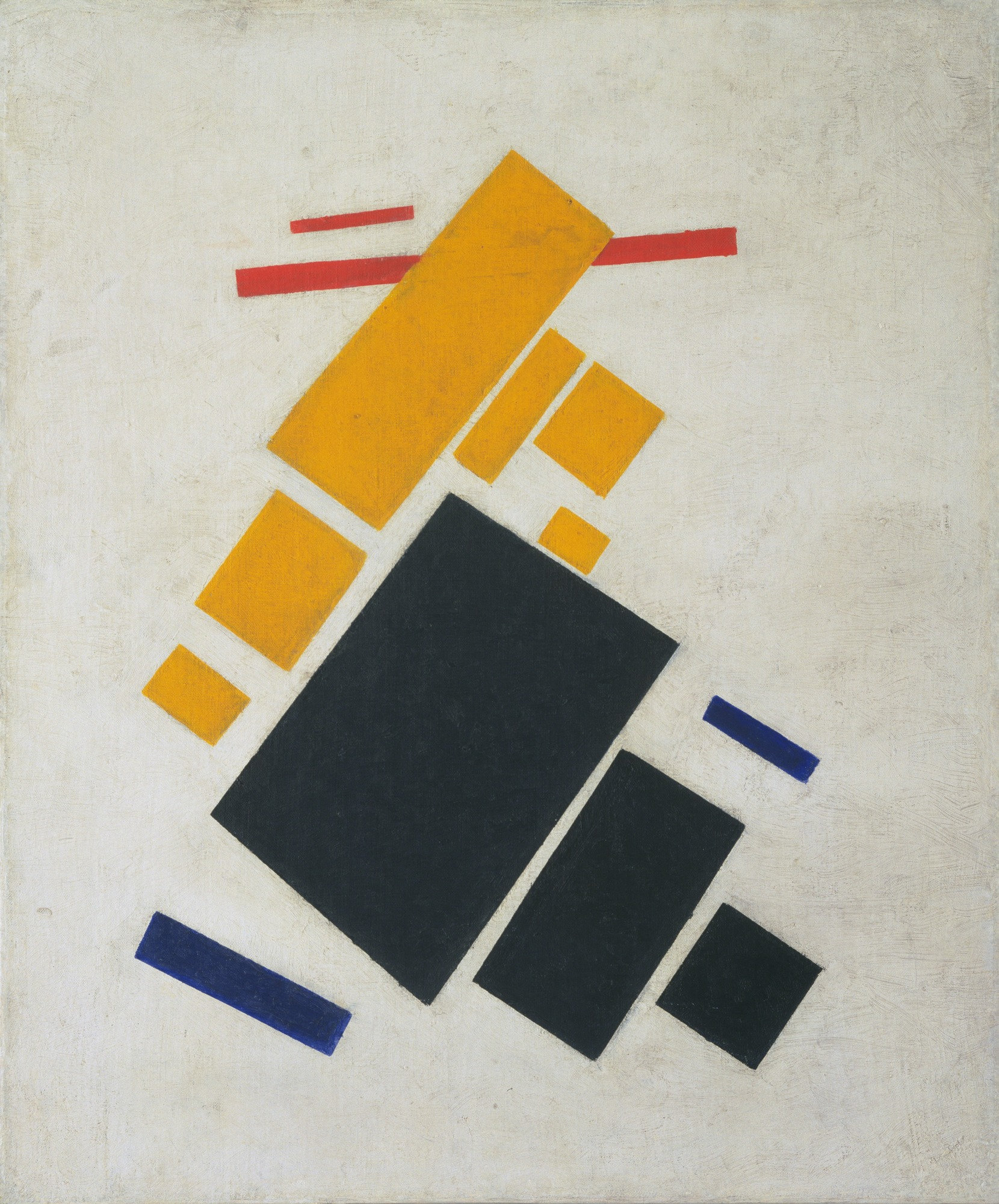

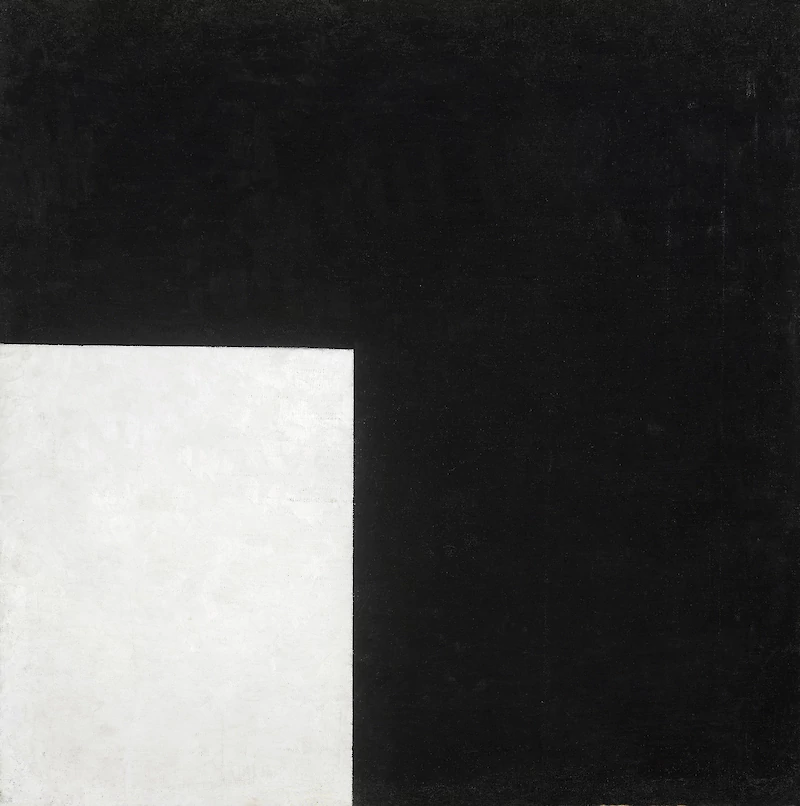

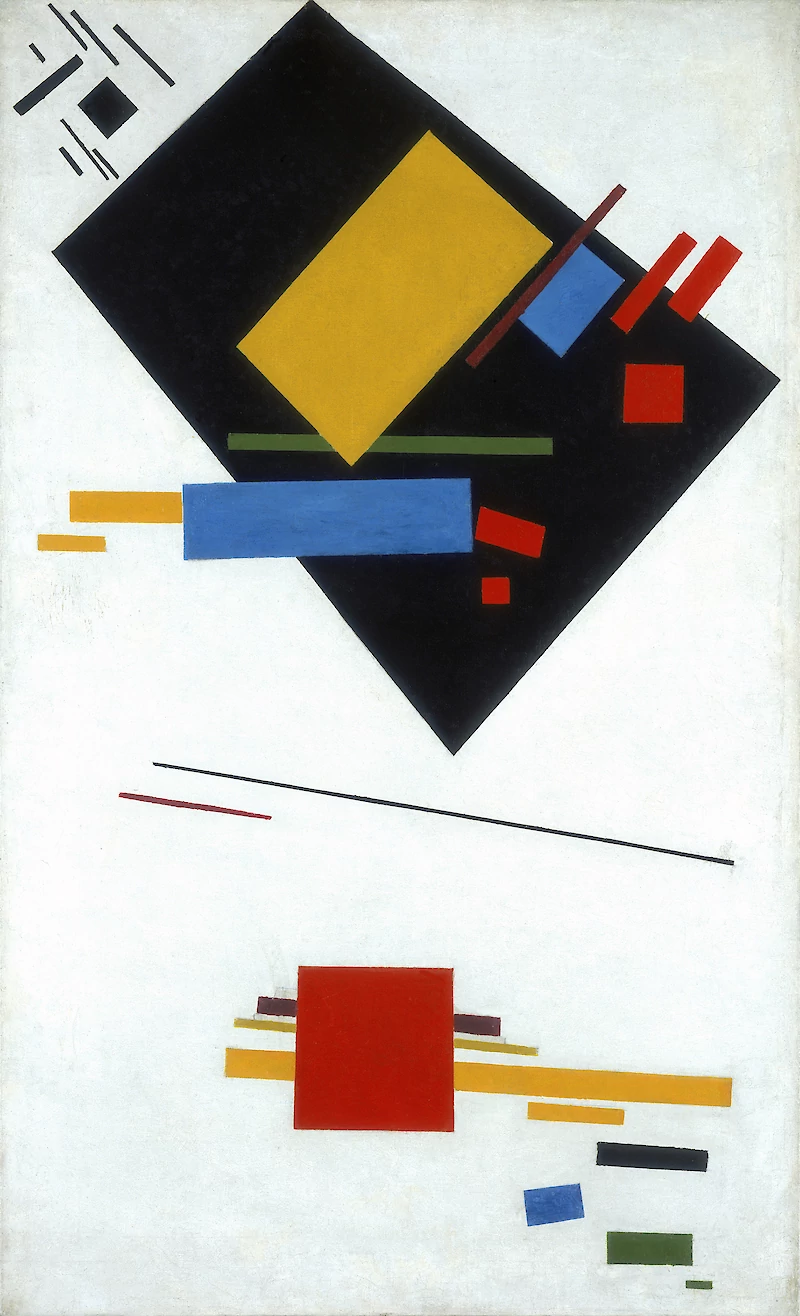

1915 is the first year of Suprematism. Malevich has left behind the complex structures of Portrait of Ivan Kliun (1913) for arrangements of simple geometric shapes. Each shape was painted in a single flat color, with the aray as a whole silhouetted against a textured white or greyish background. “I transformed myself in the zero of form,” Malevich’s manifesto read. The blank ground of Malevich’s suprematist compositions was read as a pre-revolutionary allegory: Russia’s slate needed to be wiped clean; the Czarist regime was arbitrary, inefficient, corrupt, irrational.

Started conjointly with Constructivism, though with a stronger emphasis on abstraction, from 1915 we also find Suprematism. Malevich is viewed as its founder; he coauthored the Suprematist manifesto, which calls on artists to utilize pure geometrical abstraction in painting. (The movement’s name originated from a quote of Malevich’s, in which he stated that the movement would inspire the “supremacy of pure feeling or perception in the pictorial arts.”) His central goal was to break art down to basic shapes, as well as primary and neutral colors. In 1915, Malevich stages the “0.10” Exhibition (aka The Last Futurist Exhibition).

Suprematism was imbued with spiritual and mystic undertones. Malevich was particularly interested in the mystical geometry of Peter Ouspensky (author of The Fourth Dimension, 1909), who believed artists were able to see beyond material reality and communicate their visions to others. In a pamphlet written for The Last Futurist Exhibition, Malevich echoes this conception of the artist: “I transformed myself in the zero of form… I destroyed the ring of the horizon and escaped from the circle of things, from the horizon-ring that confines the artist and the forms of nature.”

During the First World War, Jean Metzinger would co-found the second phase of the Cubist movement, referred to as Crystal Cubism. He recognized the importance of mathematics in art, through a radical geometrization of form as an underlying architectural basis for his wartime compositions.

The only contemporary Vorticist exhibition will open in London during 1915.

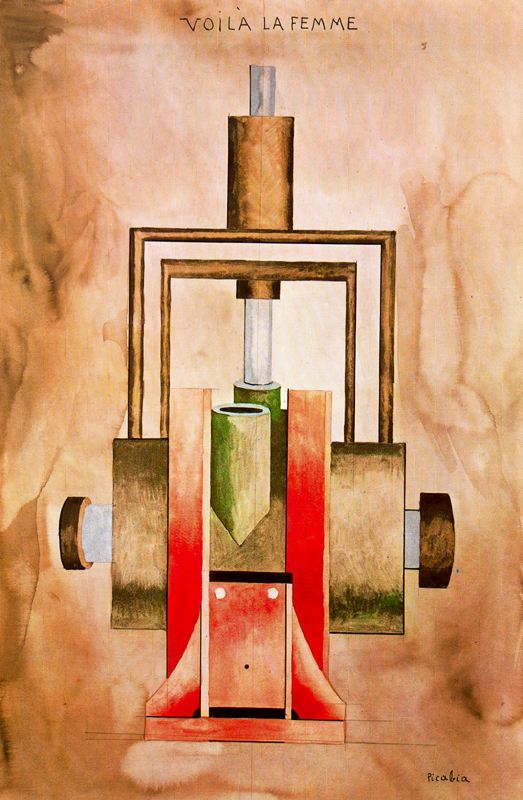

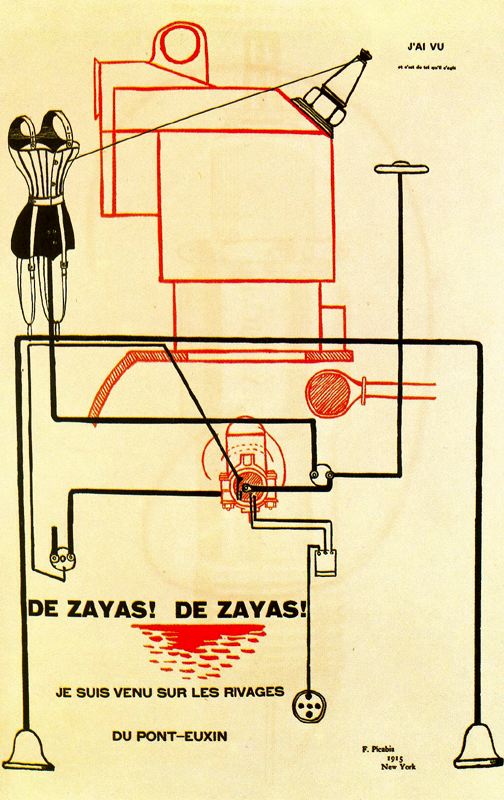

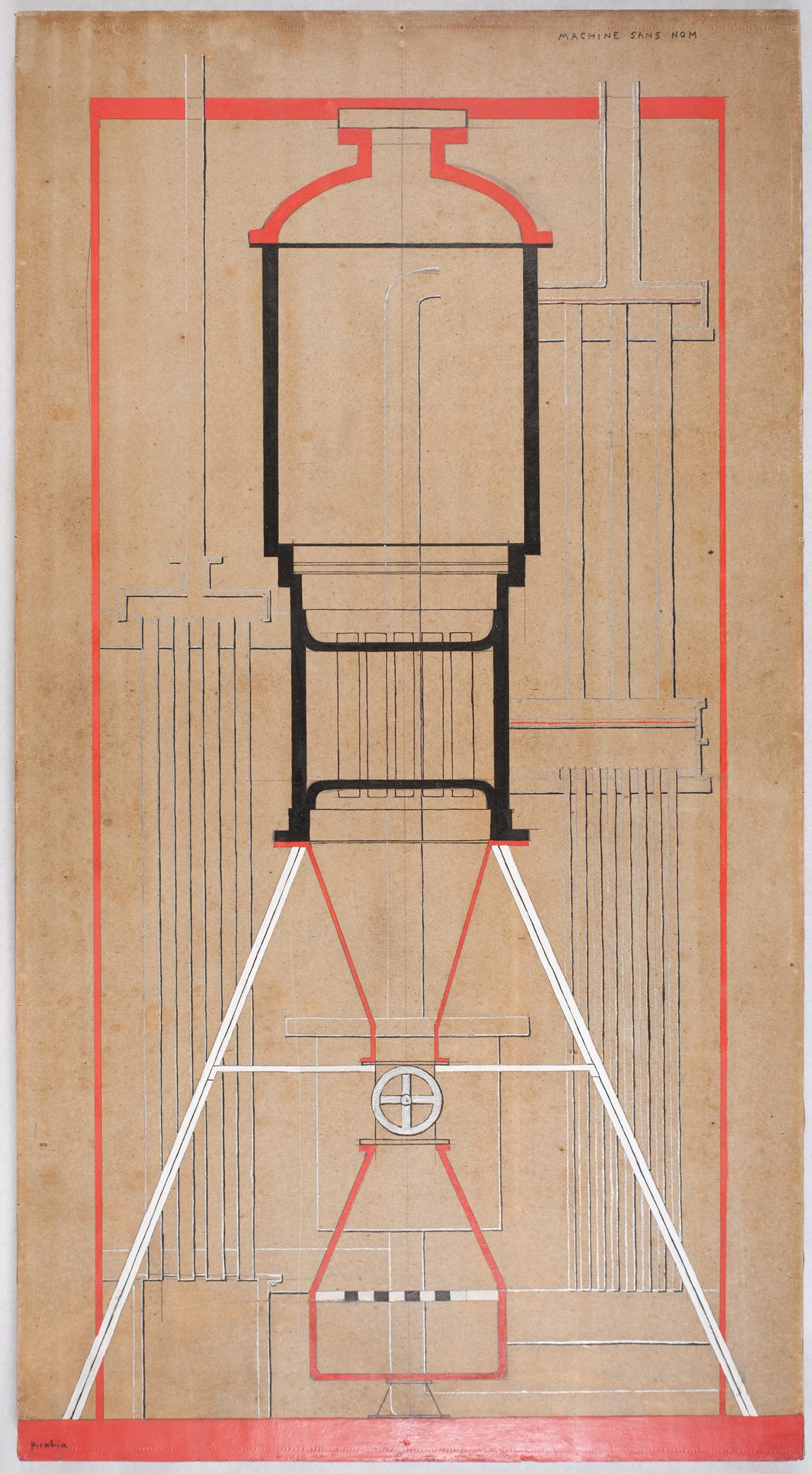

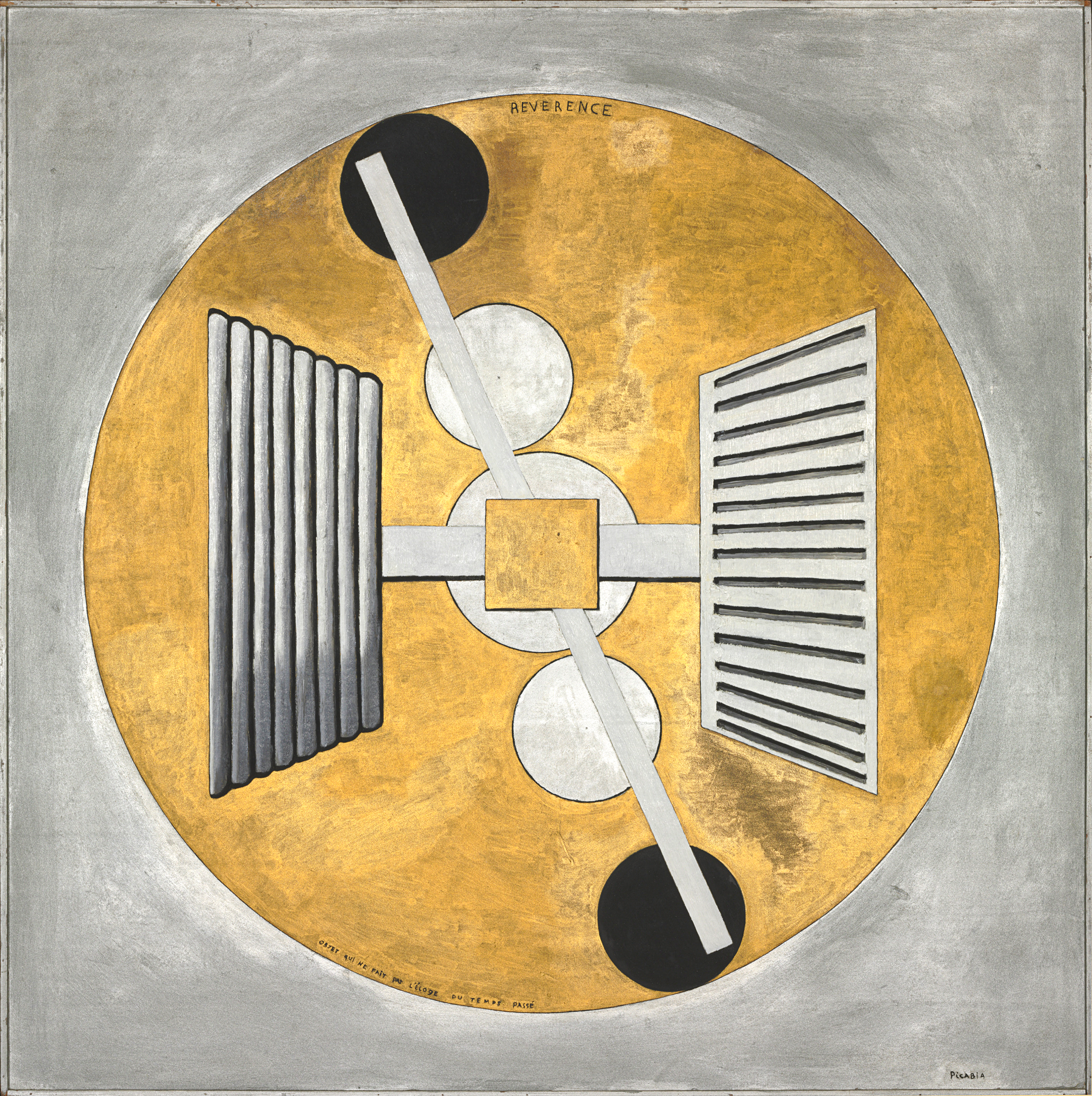

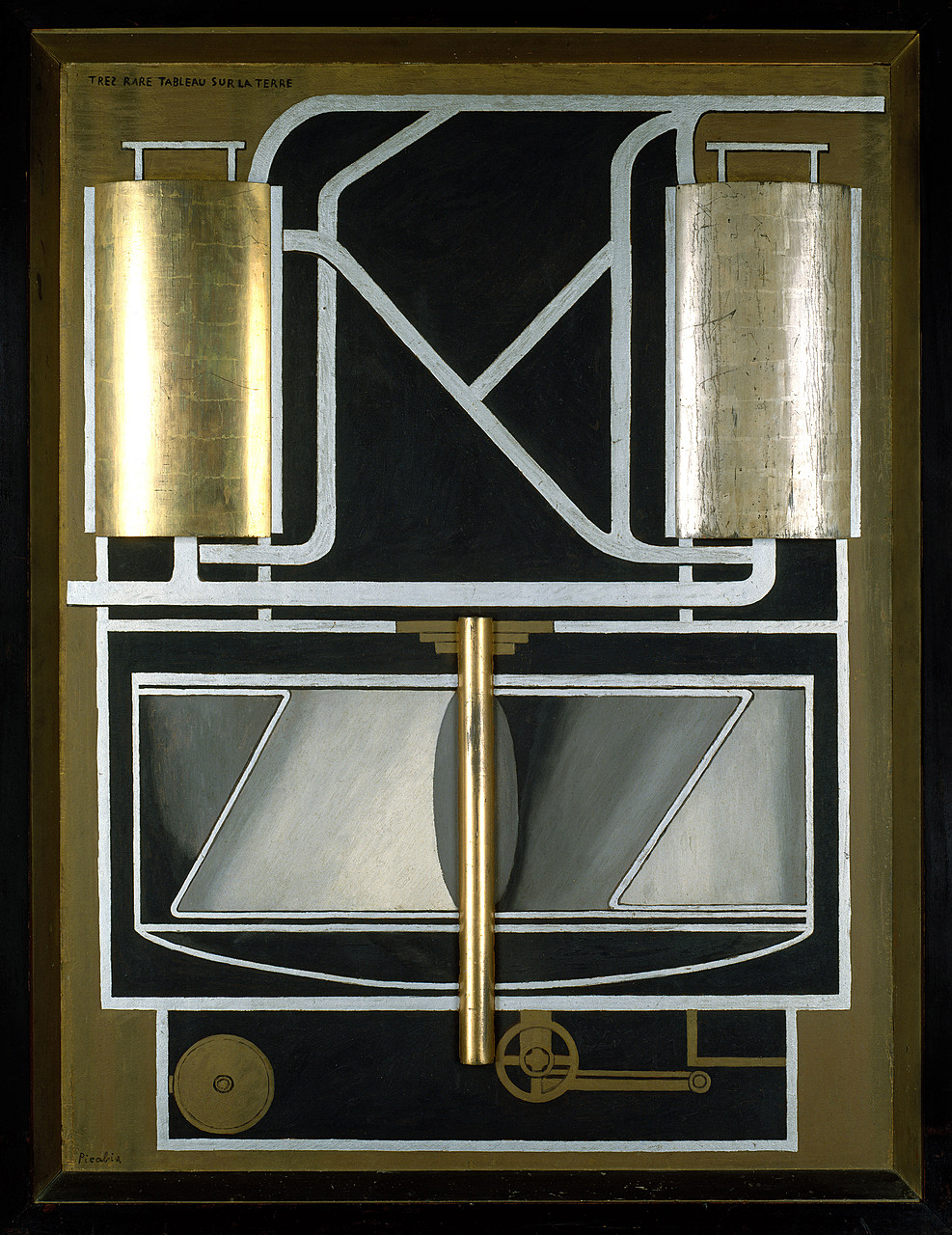

In 1915 Francis Picabia abandons his exploration of abstract form and color to adopt a new machinist idiom that he’ll use until about 1922. Unlike Robert Delaunay or Fernand Léger, who saw the machine as an emblem of a new age, he was attracted to machine shapes for their intrinsic visual and functional qualities. As can be seen below, he’ll often use “mechanomorphic” images humorously as substitutes for human beings.

Robert Innes discovers Proxima Centauri, the closest star to Earth after the Sun.

Alfred Wegener publishes his theory of Pangea, which he calls Urkontinent. (He was the first to suggest, in 1912, that the continents are slowly drifting around the Earth.) A prime example of the deeply destabilizing scientific breakthroughs of this era.

Ada Hitchins’ experimental results indicating that radium is formed by the decay of uranium are published.

Georges Claude patents the neon discharge tube for use in advertising.

The first prototype military tank (“Little Willie”) is produced. They first modern fragmentation grenades (the “Mills bomb”) also developed this year.

Also see: RADIUM AGE: 1915.

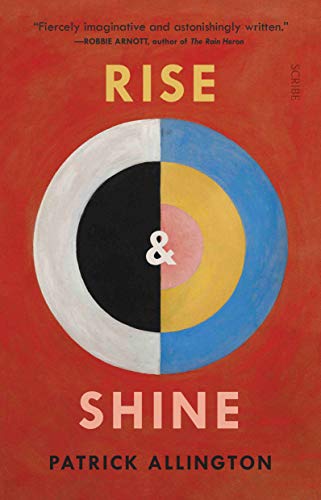

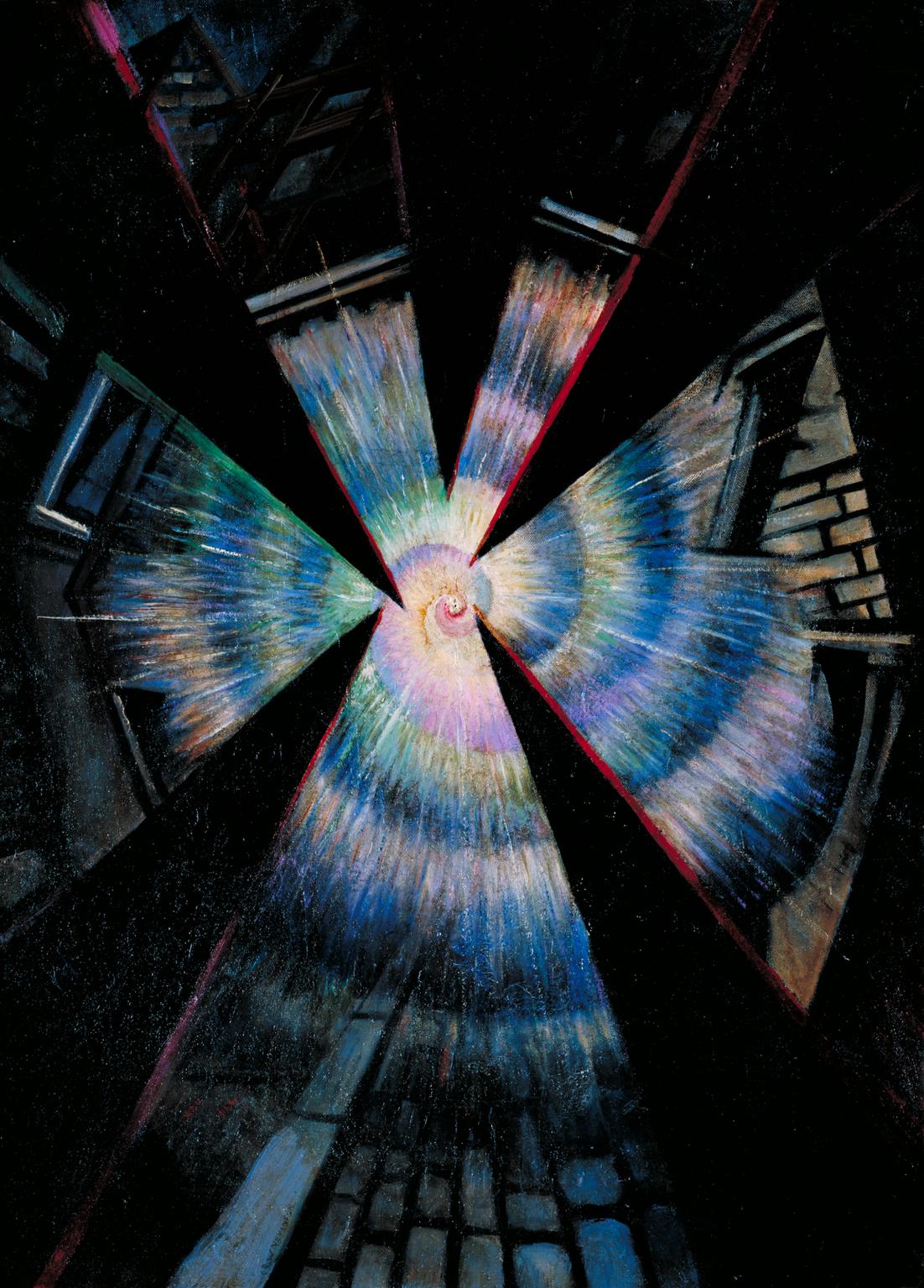

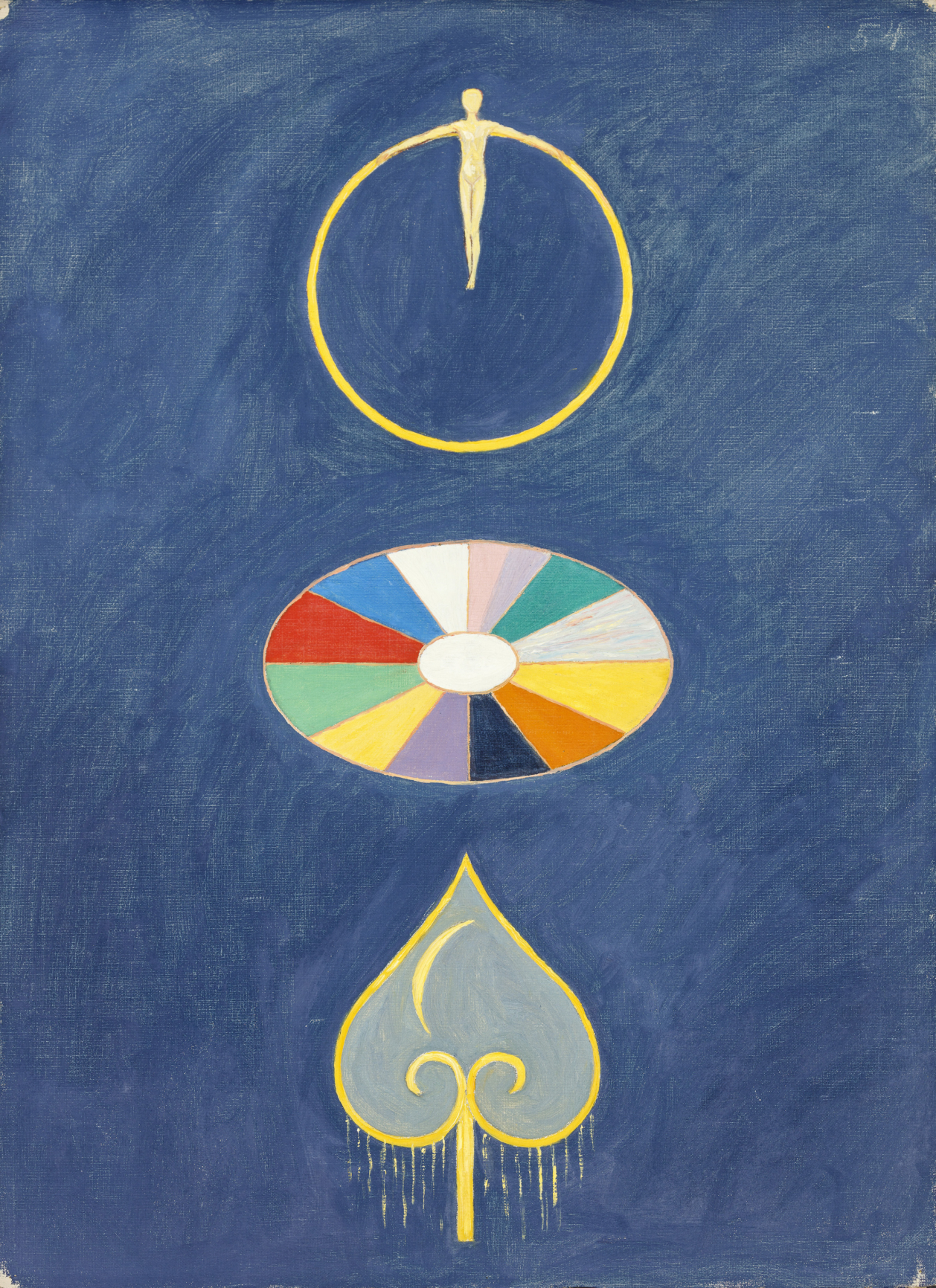

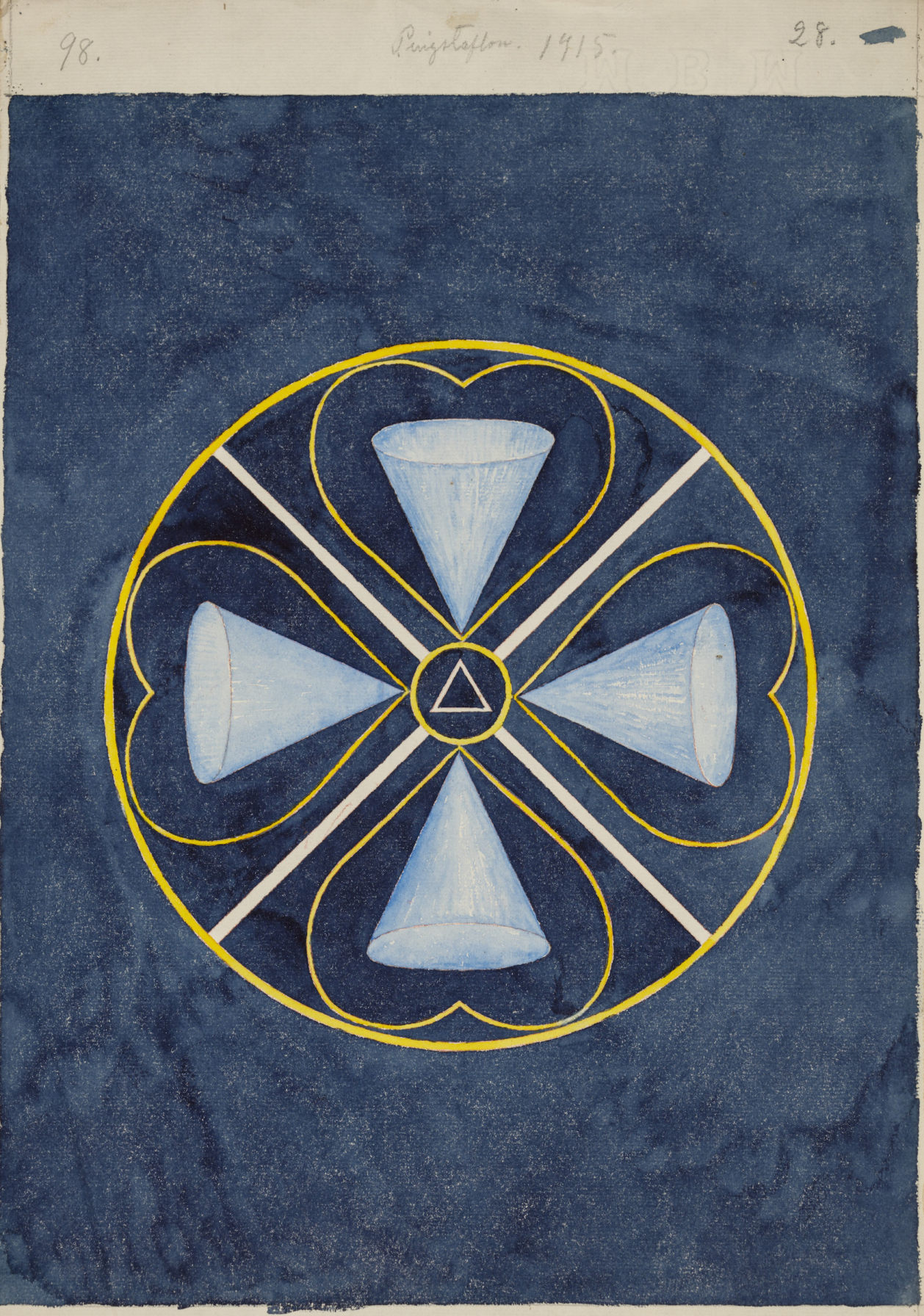

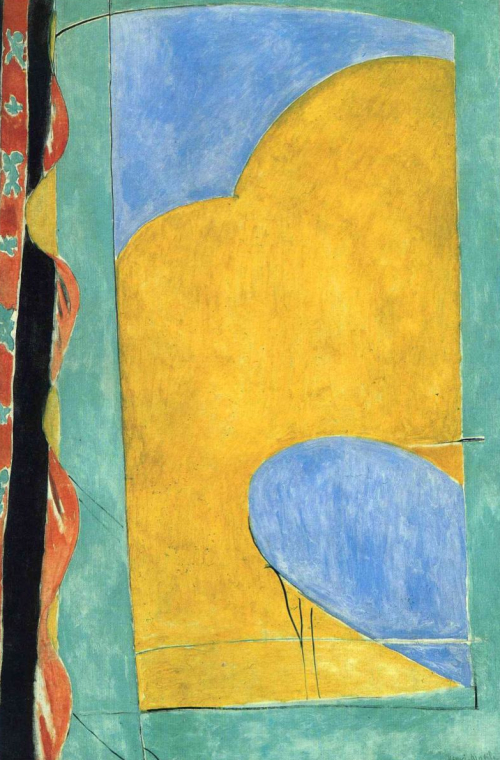

After returning to her painting, Klint’s compositions were organized around circles, triangles, and cubes. At the same time she painted pictures of white and black swans, arranged in mirror-image patterns of superimposed in the act of mating, expressing her Platonic belief that the very polarity of being points towards its need for oneness. This painting belongs tp her Swan series, though its imagery seems “unremittingly abstract,” as Pepe Karmel puts it. We have here a solar disk that points to the black/white swan motif, but also depicts the union of yellow (male, in her system) and blue (female).

PS: Klint’s “The Swan, No. 17” was used as the cover art for Patrick Allington’s 2020 post-apocalyptic sf novel Rise & Shine. (He wrote an essay about the painting here.) See below.

Excerpt from Allington’s essay:

Af Klint’s world extended beyond what we can see with the naked eye to the microscopic and invisible world. She reckoned with science as well as spirits—X-rays as well as seances. What fun she could have had with nanotechnology, with big data, with watching an egg explode in a microwave oven. In 2021, or so I happen to believe, much of the world remains hidden, to our collective detriment. Way too often, we seem content with, or resigned to, this state of affairs—we go out of our way to promote hiddenness.

Created soon after his arrival in New York in 1915, “Intervention d’une femme au moyen d’une machine” marks the abrupt progression in Picabia’s work from the Udnie series of Cubist-style paintings of 1913-14 to the mechanical portraits and “mechanomorphs” of 1915-16 which would form the defining principles of his art throughout the Dada period until the early ’20s.

Picabia appropriated a diagram of a railway machine and remade the image by painting in a background of gold, thus covering up unwanted portions of the original image. He also added areas of green gouache to the remaining visible aspects of a flywheel and shaft. The resulting collage-like image exemplifies Picabia’s interest in the metaphors of machines and sexuality: as the flywheel turns, the shaft moves up and down replicating the mechanics of sexual intercourse. Further, the idea of a girl born without a mother is a reverse ‘virgin birth’, of an entity ‘born’ of the male, industrialized world.

This work depicts a symmetrical ‘female’ machine, iconic rather than functional. The central double cylinders, and the blue piston shaft that penetrates one of them, suggest a sexual theme.

Picabia’s first machine drawings, published in the summer 1915 issue of Stieglitz’s “291,” were allegorical portraits of people in his circle. Careful inspection reveals this line drawing to be based on an electric diagram of an automobile, with two headlights at the bottom corners and a spark plug just right of center at the top. There are a number of schematic electro-mechanical components and wiring that attaches to the crotch and left breast of an empty woman’s corset.

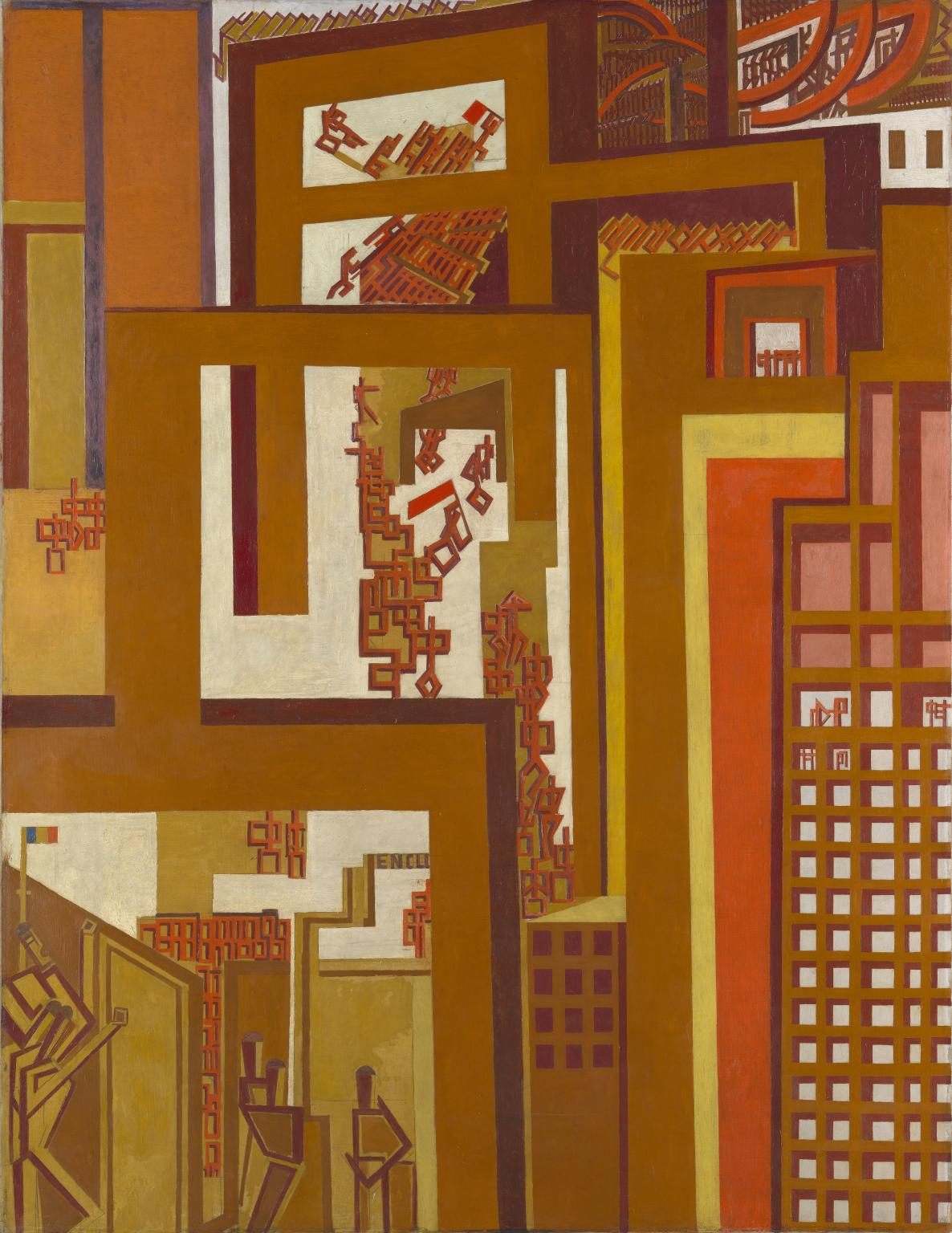

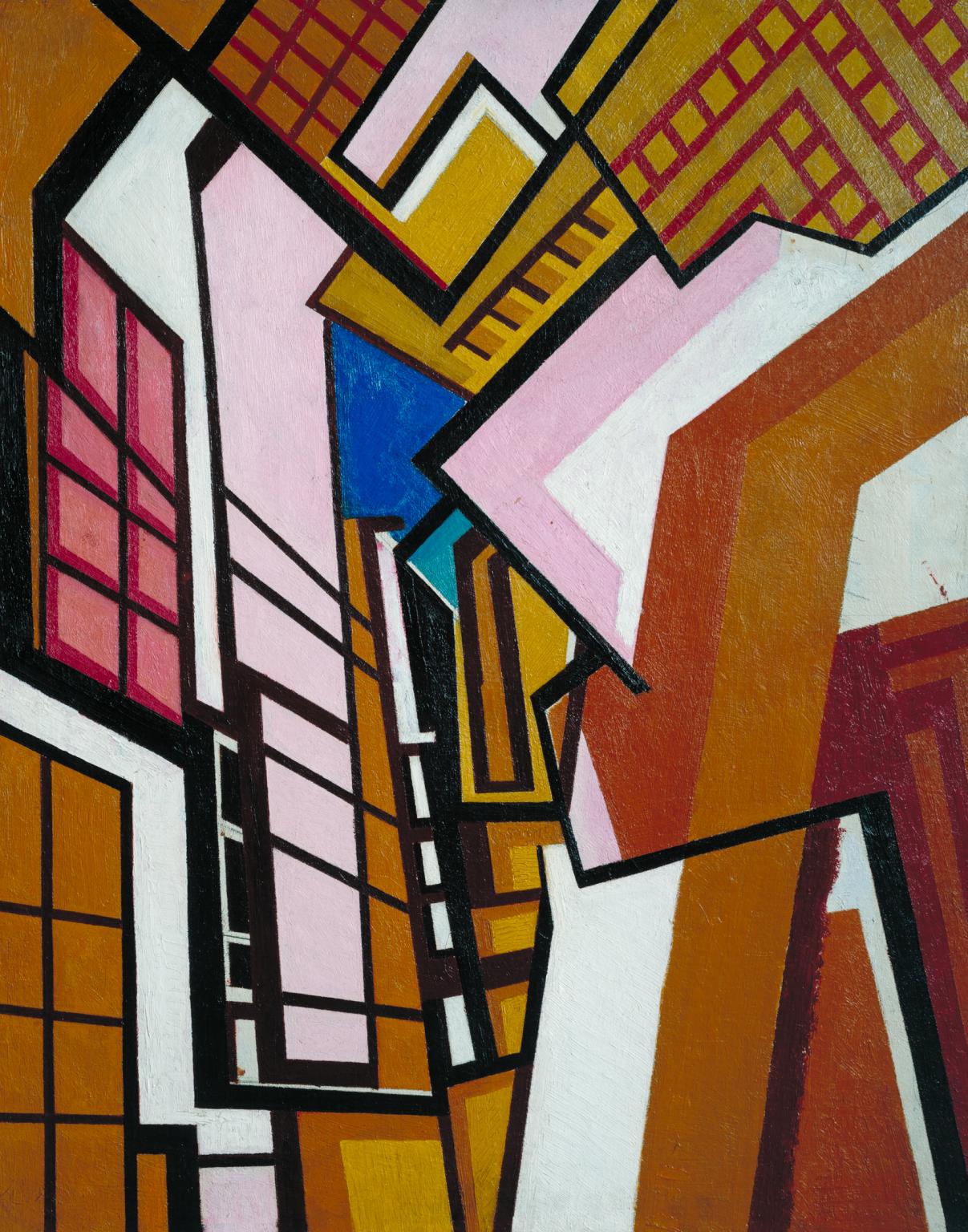

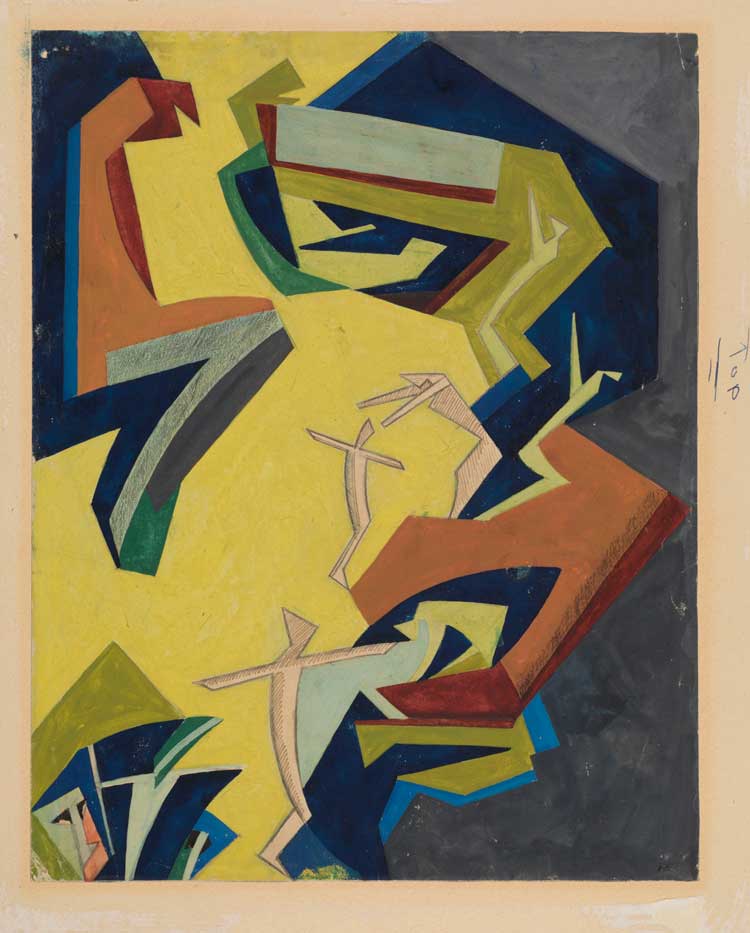

Wyndham Lewis painted the Vorticist composition The Crowd in 1914 or 1915. The motif was inspired by the outbreak of World War I, which made Lewis think about power and crowd manipulation. This was the subject of an article he wrote for the second issue of the Vorticist magazine Blast, published in July 1915, titled “The Crowd Master, 1914, London, July”.

The Crowd presents an abstract city with high-rise buildings and small, heavily stylized human figures. At the top right is a group of structures reminiscent of industrial buildings. People scattered around the picture appear to climb upwards, away from the geometrical enclosure of the city, and towards the structures at the top. At the bottom left is a small group of larger although also stylized figures holding a flag.

Michael Prodger of the New Statesman wrote that The Crowd is one of Lewis’ three most important works and called it “the purest example of his vorticism”. Prodger compared it to the film Metropolis.

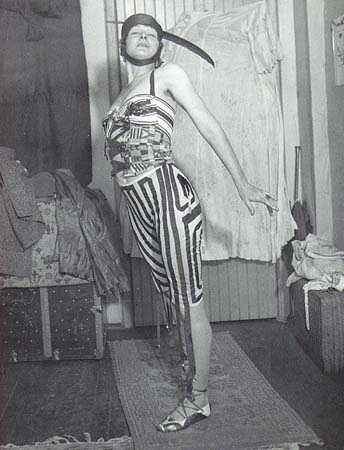

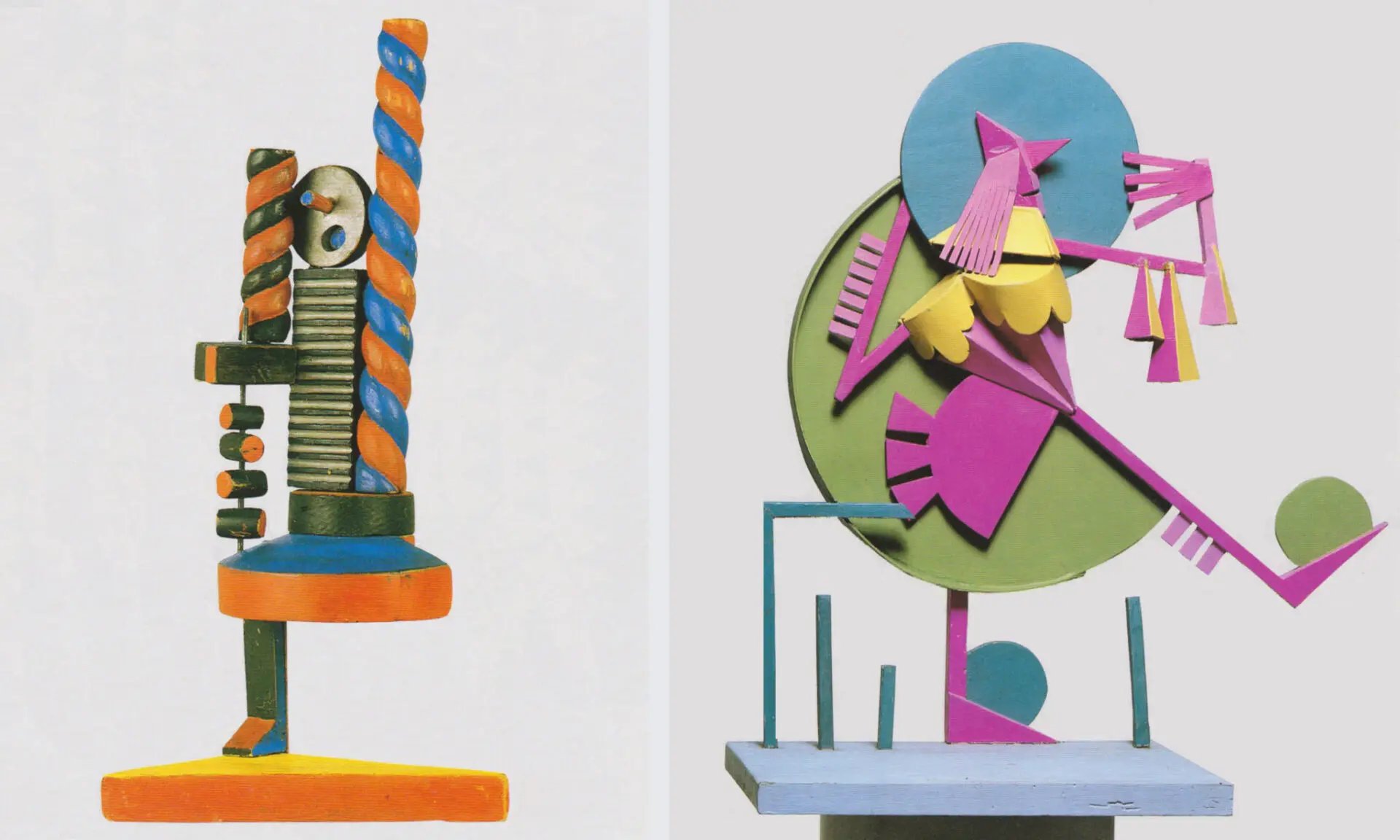

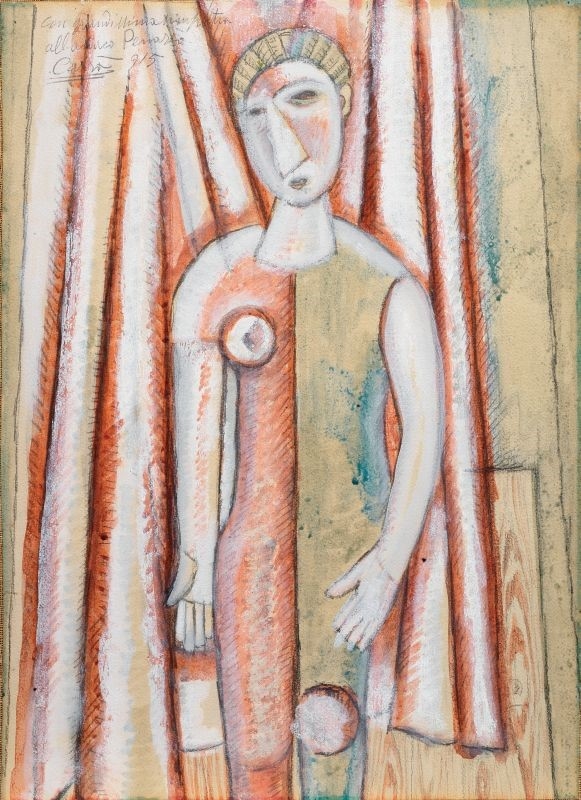

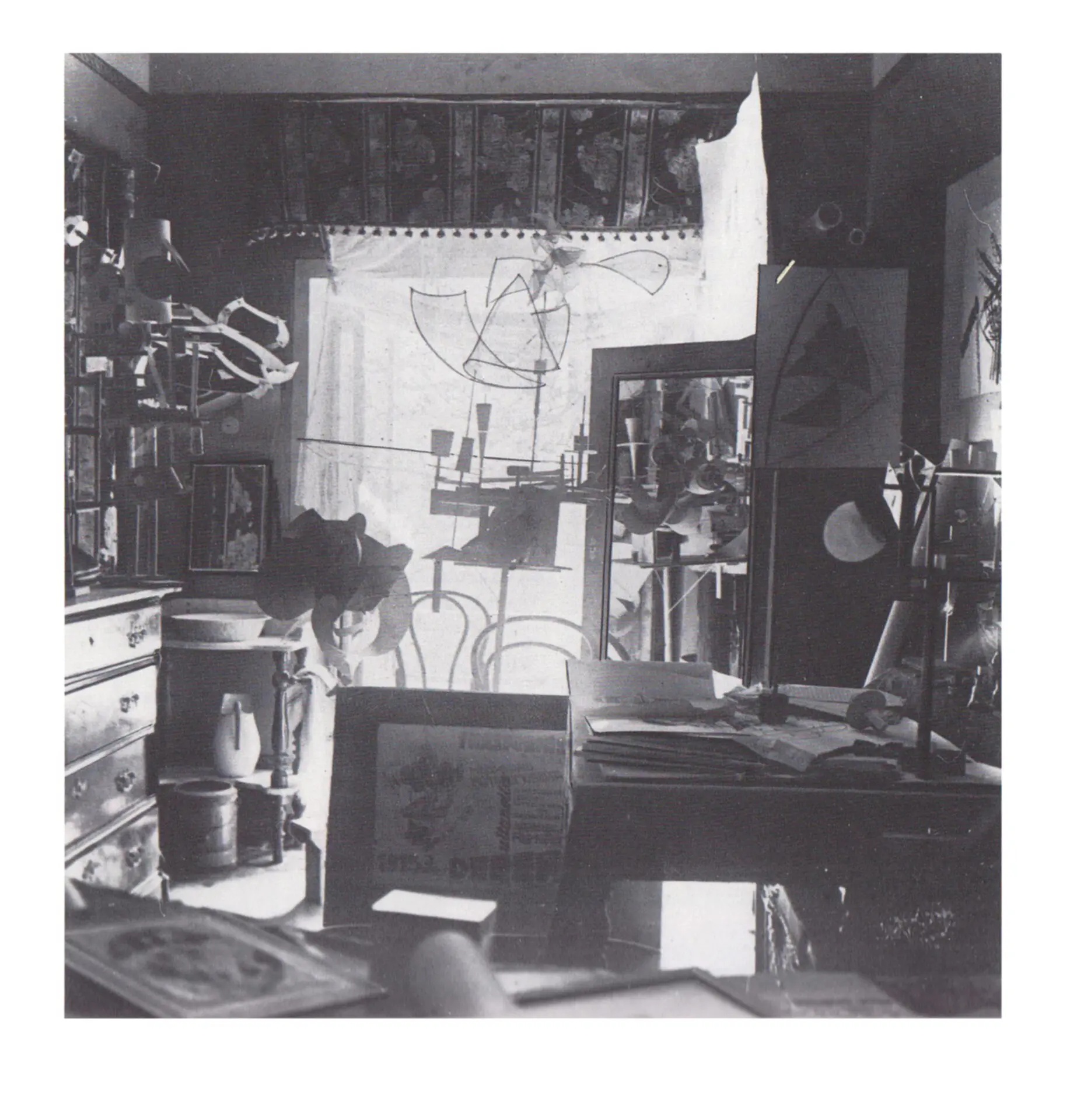

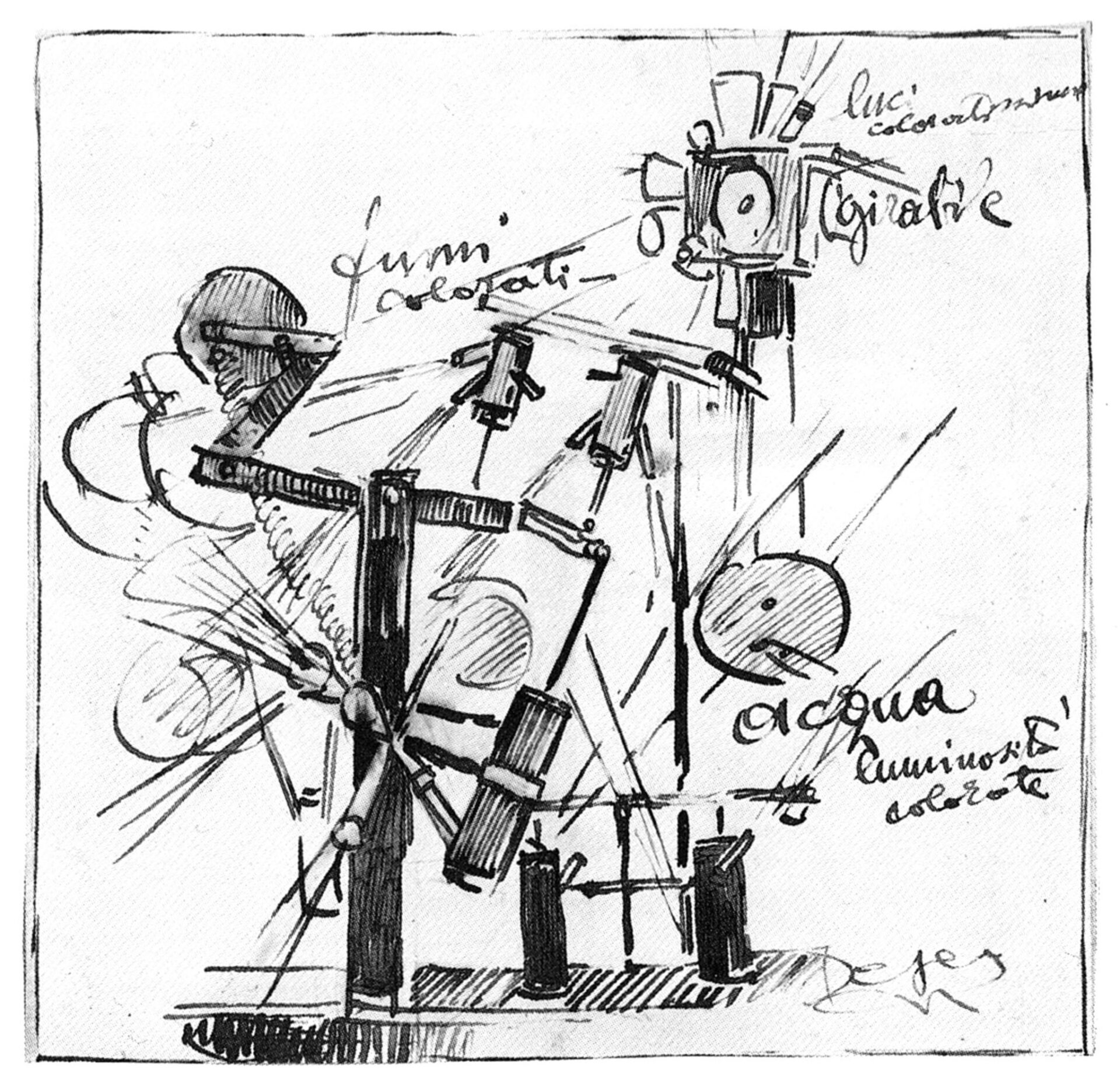

Fortunato Depero’s noisy, movable, polymaterial sculptures of 1913–1915 were a complement to a marionette he called essere vivente artificiale (Artificial Living Being). This organism was designed to operate as an actor in a scenic environment with “rhythmically vibrating elements, from which will emerge and disappear animals and clouds, open and close doors, windows, eyes and mouths.” The innocence and playfulness of these constructions ensured that they would stimulate in the audience a sense of wonder, amazement, fascination, and joy.

Info from the Center for Modern Italian Art.

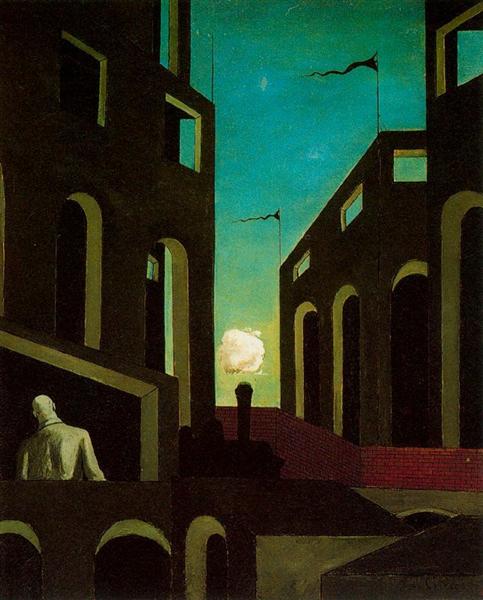

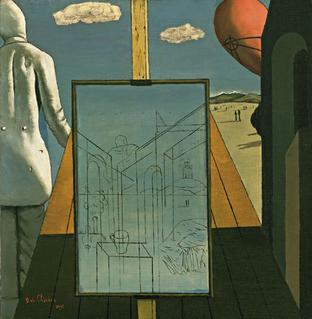

The painting depicts apparently related but separate scenes. The scene on the left shows a statue of a man in a frock-coat from behind. The statue appears to be staring contemplatively into an open sky. The two scenes are separated in the middle by a wooden beam, perhaps part of an easel. Near the base of the beam is a blueprint drawing of an interior, in which large arches and a window open onto a landscape including the stick-like figures of two men meeting, and distant mountains. The scene on the right appears to be looking down on the same landscape from a slightly different angle. Above the landscape is the shape of the head of a tailor’s dummy.

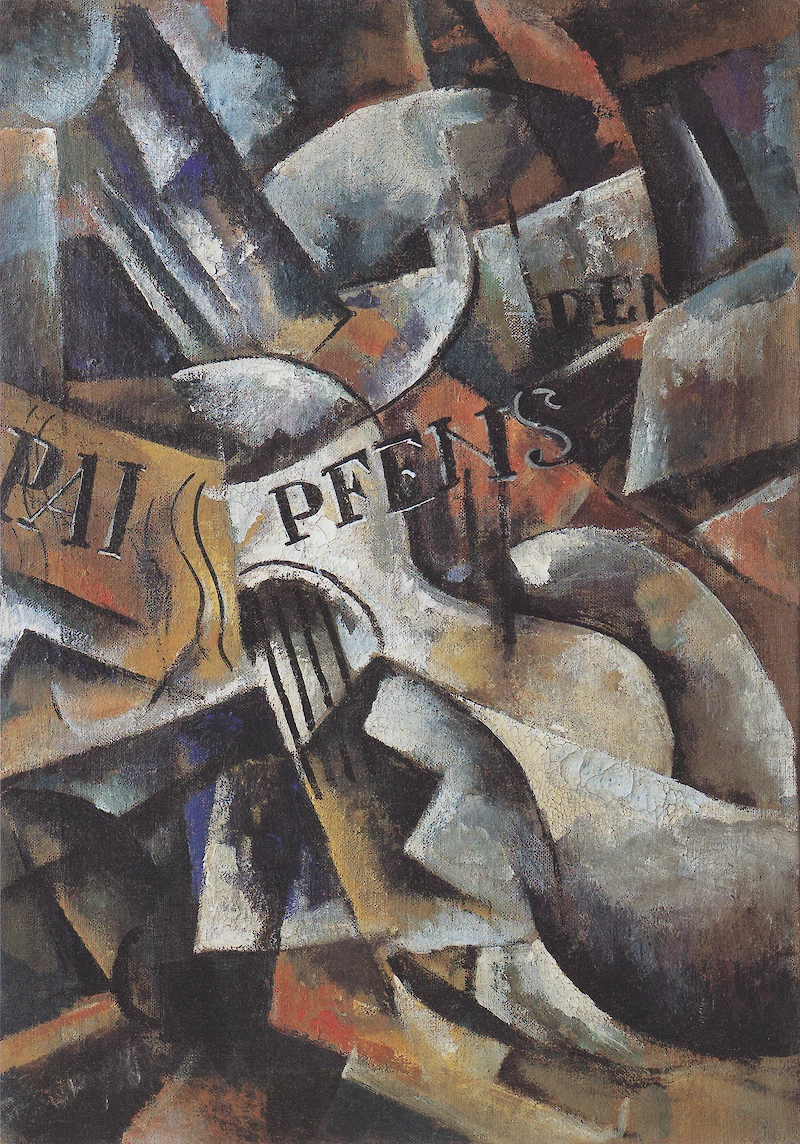

Arranged on a table painted to imitate wood graining are a newspaper (with the masthead “Le Journal”), a bottle of Médoc wine, a fruit dish, a glass, and a carafe. Objects appear refracted by shafts of colored light in daring combinations entering through the window.

Tom Gibbons associates x-rays with the transparent overlays in Gris’s painting. (See Linda Dalrymple Henderson.) Also see Tom H. Gibbons’s “Cubism and ‘The Fourth Dimension’ in the Context of the Late Nineteenth-Century and Early Twentieth-Century Revival of Occult Idealism” (1981).

Pepe Karmel suggests, in Abstract Art: A Global History that what we’re seeing here is a face, deconstructed and flattened into simple shapes, then rearranged. Malevich wants the viewer to respond to the pictorial quality of each of the painting’s elements before (or instead of) asking about its possible figurative value. It’s not a “pure” abstraction, in other words; in fact, its subliminal resemblance to a face creates in the viewer an anticipation of symmetry. Karmel claims that the painting functions as an allegorical narrative of social destruction and reconstruction.

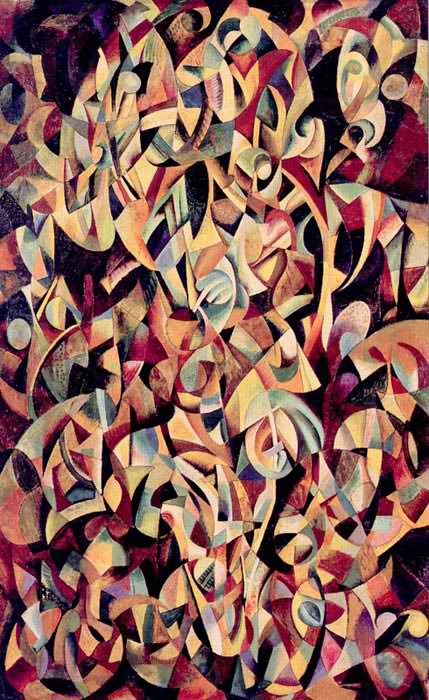

From the Whitney’s website: “Max Weber, himself an immigrant, sought to capture the hustle-and-bustle and ornate décor typical of New York’s Chinese restaurants. He achieved these effects by assimilating the lessons of French Cubism, evident in the kaleidoscopic composition of fragmented forms, fractured planes, and patterned sections that recall the wallpaper often incorporated in Cubist collage.”

While serving as a medical orderly during World War I in Sainte-Menehould, France, Metzinger bore witness to the ravages of war firsthand. Rather than depicting such horrors, Metzinger chose to represent a poilu sitting at a game of chess, smoking a cigarette. The military subject of this painting is possibly a self-portrait.

This distilled form of Cubism, soon to be known as Crystal Cubism, is consistent with Metzinger’s shift, between 1914 and 1916, towards a strong emphasis on large, flat surface activity, with overlapping geometric planes. The manifest primacy of the underlying architectonics of the composition, entrenched in the abstract, controls practically all of the elements of the painting. (Note the structuralist parallels here — the underlying structure determines but does not entirely decide the other elements.)

See 1913 and 1914 installments for more on Hartley’s war paintings.

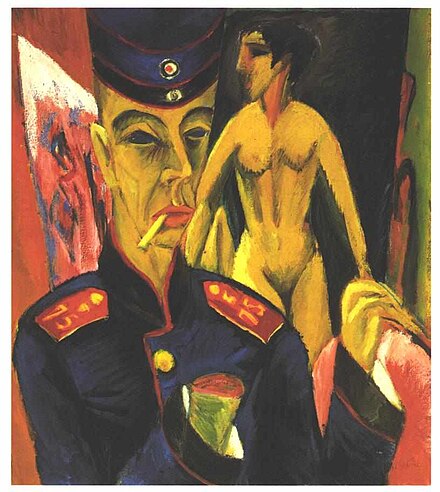

At the onset of the First World War in September 1914, Kirchner volunteered for military service. In July 1915 he was sent to Halle an der Saale to train as a driver in the reserve unit of the 75th Mansfeld Field Artillery Regiment. Kirchner’s riding instructor arranged for Kirchner to be discharged after a mental breakdown. Kirchner then returned to Berlin and continued to work, producing many paintings including Self-Portrait as a Soldier (1915).

The subjects are abstracted into angular geometric blocks of colour, becoming dehumanised components in a machine of death. Nevinson later wrote: “To me the soldier going to be dominated by the machine … I was the first man to express this feeling on canvas.”

Made in 1915 while the artist was on honeymoon leave from service as an ambulance driver with the RAMC on the Western Front in the First World War. In an article in 1916, artist Walter Sickert called the work “the most authoritative and concentrated utterance on the war in the history of painting.”

From Smarthistory (the center for public art history):

Kazimir Malevich’s Airplane Flying: Suprematist Composition does not depict an airplane. Instead, it was intended to convey the sensation of mechanical flight using thirteen rectangles in black, yellow, red, and blue placed in dynamic relationships on a white ground. Movement is created by the diagonal orientation of the rectangles in relation to the edges of the canvas. Groups of individual colors suggest distinct objects shown at varying distances as they increase or diminish in scale. Ascension is implied by the point of the yellow rectangle centered at the top of the composition, while the bright yellow and red rectangles float above the heavier dark blue and black rectangles.

A self-generating, almost symmetrical machine is presented frontally, clearly silhouetted against a flat, impassive background. Some critics see in it the evocation of a sexual event in mechanical terms. Certainly, this dispassionate view of sex is consonant with the antisentimental attitudes that were to characterize Dada. The work has also been interpreted as representing an alchemical processor, in part because of the coating of the two upper cylinders with gold and silver leaf respectively.

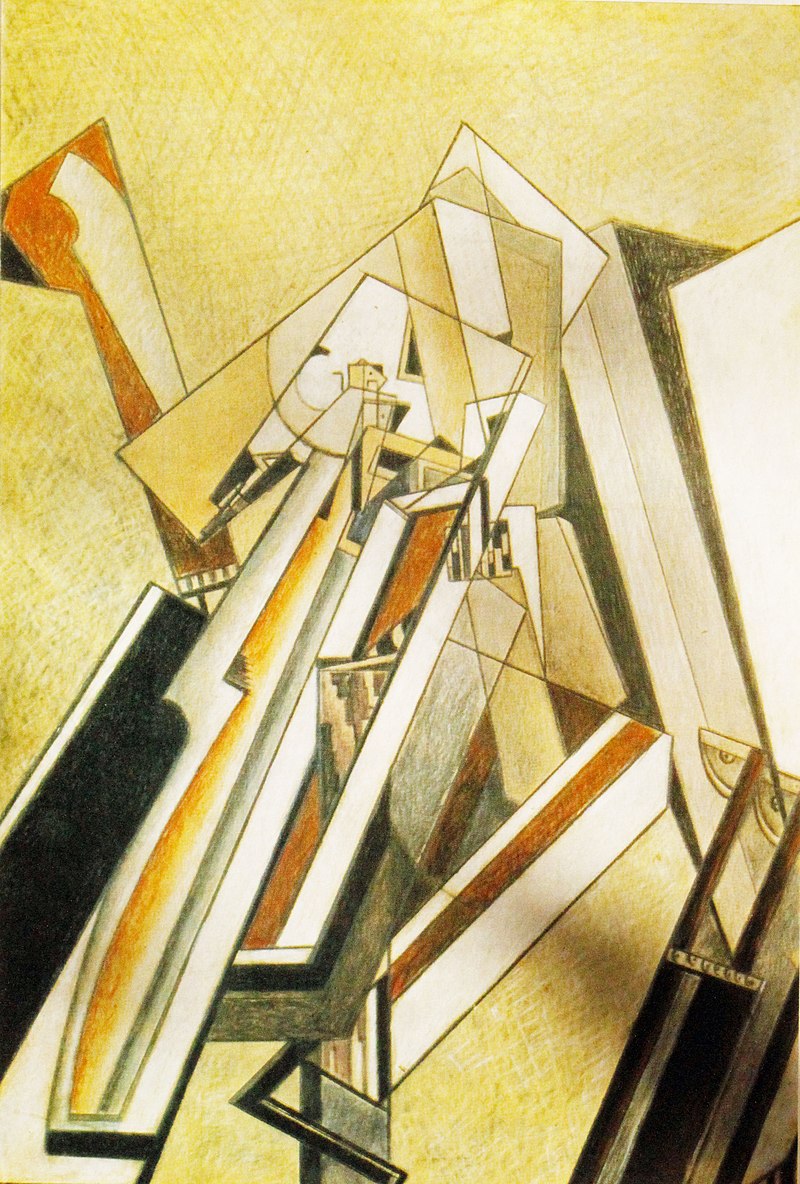

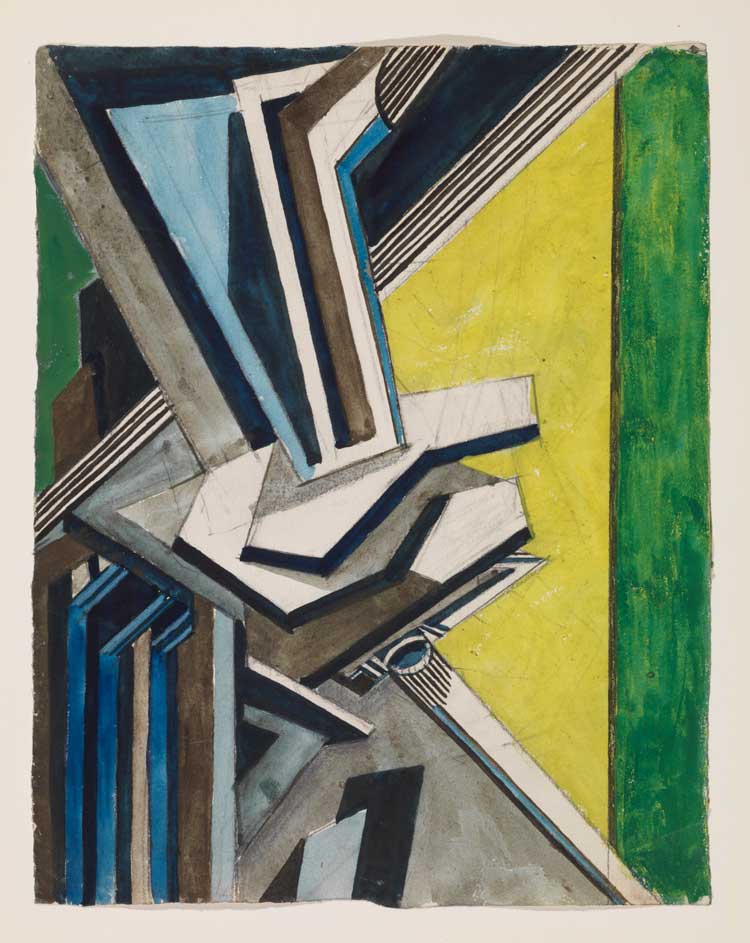

Lyubov Popova’s “Cubist construction (Portrait of a philosopher)” (1915)

The first version was completed in 1915 and was described by the artist as his breakthrough work and the inception for the launch of the Suprematist art movement (1915–1919). In his manifesto for the Suprematist movement, Malevich said the works were intended as “desperate struggle to free art from the ballast of the objective world” by focusing only on pure form.

The original Black Square was first shown at The Last Futurist Exhibition 0,10 in 1915. It is often described as the “zero point of painting,: given its groundbreaking, paradoxical monumental and reductive approach, which remains today a huge influence on minimalist art.

Malevich himself described Black Square as ”the first step of pure creation in art” and “the embryo of all potentials.”

A note about Black Trapezium and Red Square — it’s a version of a 1913 sketch that Malevich did for the play Victory Over the Sun. In the original sketch, which was titled “Interplanetary Travel,” one finds three conical spaceships flying in different directions; they are not represented in this abstraction.

Malevich’s concept of Suprematism sought to develop a form of expression that moved as far as possible from the world of natural forms (objectivity) and subject matter in order to access “the supremacy of pure feeling” and spirituality.

Malevich sought a form of art that was free from previous conceptions of color, shape and perspective. He believed that the purely pictorial aspect of painting was superior to all other elements in painting, and needed to be liberated from recognizable representations of reality. Suprematism was influenced by Russian Cubo-Futurism. Principal elements were movement, simultaneity and cosmic insights.

Early on, Malevich worked in a variety of styles, quickly assimilating the movements of Impressionism, Symbolism and Fauvism and, after visiting Paris in 1912, Cubism. Gradually simplifying his style, he developed an approach with key works consisting of pure geometric forms and their relationships to one another, set against minimal grounds. In addition to his paintings, Malevich laid down his theories in writing, such as “From Cubism and Futurism to Suprematism” (1915).

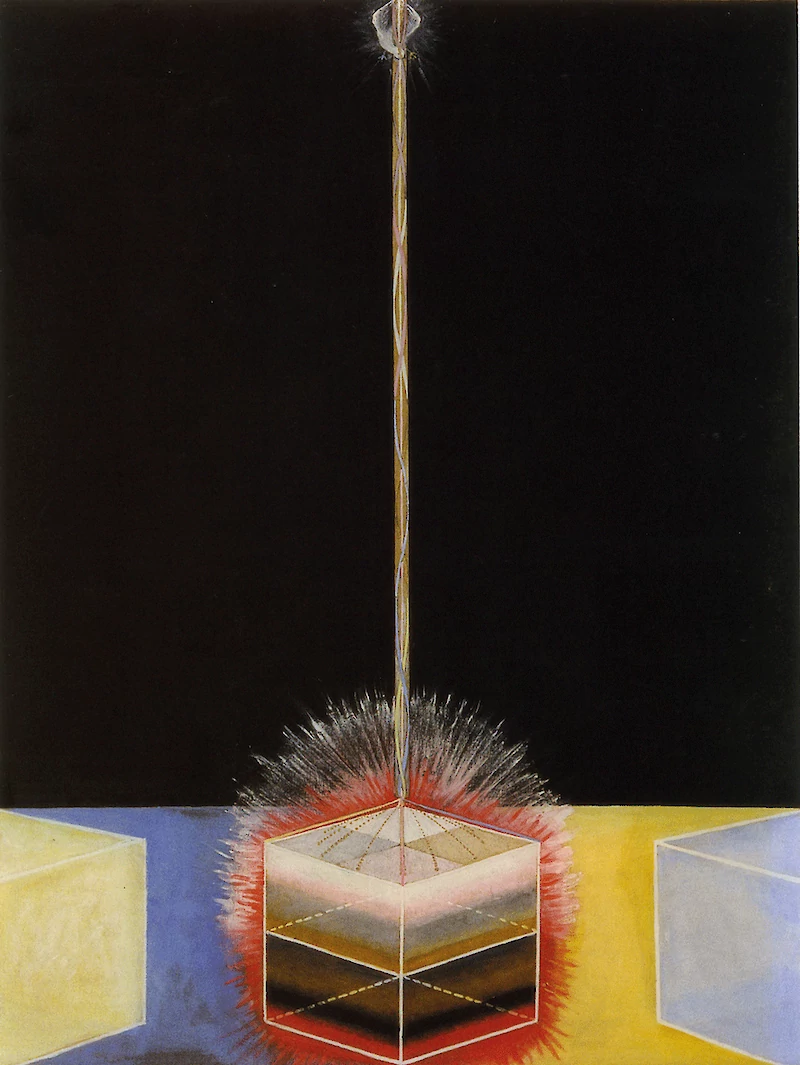

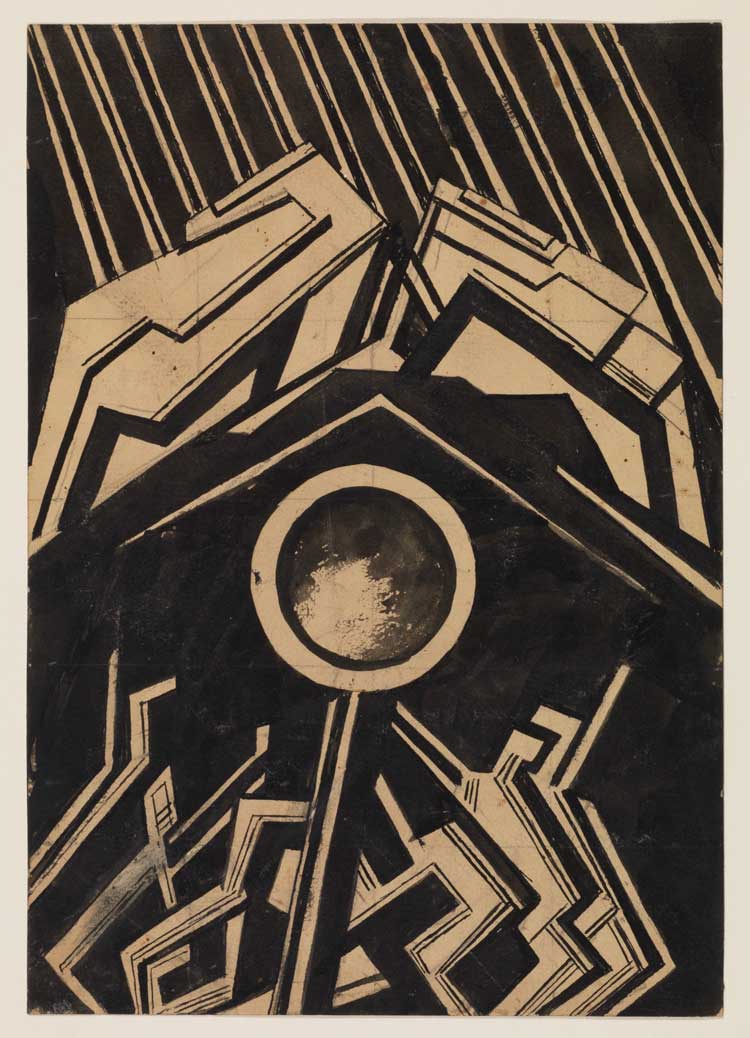

Af Klint’s “Paintings for the Temple” culminate with the large “Altarpiece” trio. Two of these depict stepped equilateral triangles, one pointing upwards, the other standing on its apex; they flank a central panel containing a gilded orb whose thick black outline, like a protective membrane, almost touches the edges of the canvas. The theosophist’s six-pointed star, surrounded by a circle, looks out from the centre. The physical world aspires upwards, towards the ethereal rays of light; the spirit world descends, becoming darkened by form.

A pyramid representing spiritual growth, topped by a circular sun of mystical illumination.

Amy Sherlock’s Royal Academy essay, from which the description above is drawn, claims the following: “When Af Klint returned to her brushes [in 1912, after spending several years cring for her mother], she was less directly influenced by spirit guidance. Crisper geometric forms emerge in the paintings; her palette is less diluted, her symbols more deliberate.”

As a sculptor, Fortunato Depero was indebted to Giacomo Balla’s research into movement, abstract line-forces, light, and pictorial equivalents to sound impressions. Consequently, he moved away from conventional static constructions and began to work on kinetic assemblages, which he called Complessi plastici (Ensembles Plastiques). Further inspiration was provided by Carlo Carrà’s manifesto La pittura dei suoni, rumori, odori (The Painting of Sounds, Noises and Smells) of August 1913, which similarly discussed insiemi plastici astratti (abstract plastic wholes) as “corresponding not to our sight but to the sensations which derive from sounds, noises, and smells.”

Depero pursued a trajectory that led progressively from polymaterial sculpture to plastic architecture to “colorful compounds in motion,” in which he tried to give expression to “mobility and the magic sense of transformation” as well as “our mechanical, electro-speedy, magically artificial and ultra-noisy sensibility.”

Info from the Center for Modern Italian Art.

Dismorr and Atkinson were Vorticists…

According to The Met:

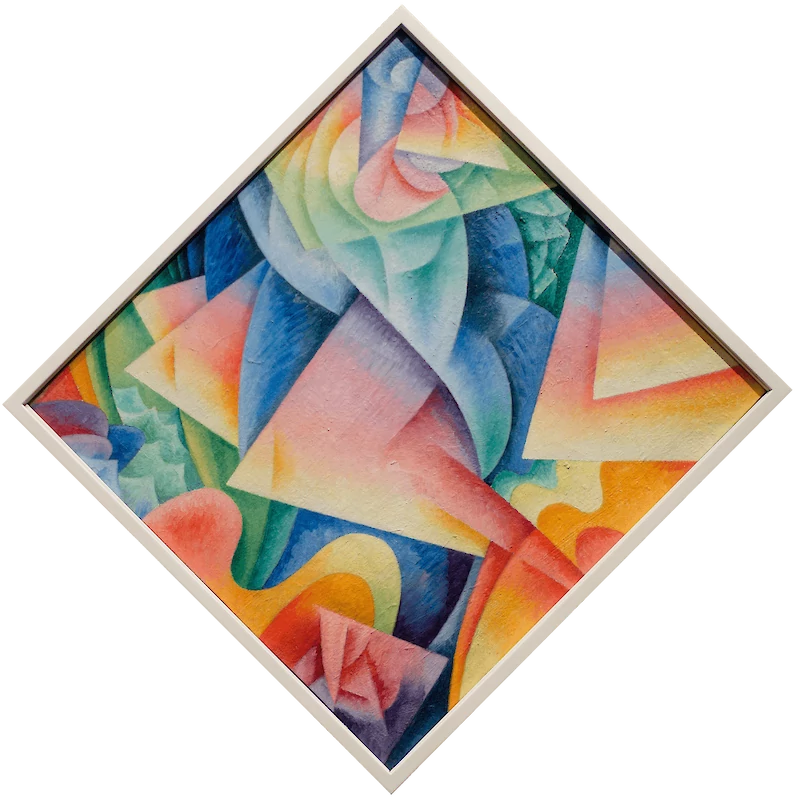

Like other artists associated with Italian Futurism, Severini was fascinated by the interactions of movement and matter and the dynamic speeds of the modern world. In his manifesto […] he describes the sensory and visual “analogies” that resonate across seemingly unrelated objects, from a dancing girl to a rushing express train to abstract forms.

Here, he uses the same shapes and colors to convey the movements of a dancer, a spinning airplane propeller, and the rolling sea. The painting’s unusual diamond shape — the only example in Severini’s oeuvre — enhances the disorienting effect of simultaneous motion.

Matisse’s original title for the painting, Composition, draws attention to its abstract quality. Interviewed in 1931, Matisse explained that the painting represents a view from a curtained window in his home at Issy-les-Moulineaux.

NOTES ON “CRYSTAL CUBISM”

Crystal Cubism (French: Cubisme cristal or Cubisme de cristal) is a distilled form of Cubism consistent with a shift, between 1915 and 1916, towards a strong emphasis on flat surface activity and large overlapping geometric planes. The primacy of the underlying geometric structure, rooted in the abstract, controls practically all of the elements of the artwork.

NOTES ON DUCHAMP’s “READYMADES”

Duchamp’s “readymades” are ordinary manufactured objects that the artist selected and modified, as an antidote to what he called “retinal art.” By simply choosing the object (or objects) and repositioning or joining, titling and signing it, the found object became art.

He selected the pieces on the basis of “visual indifference,” and the selections reflect his sense of irony, humor and ambiguity: he said “it was always the idea that came first, not the visual example … a form of denying the possibility of defining art.”

Pulled at 4 pins, 1915. An unpainted chimney ventilator that turns in the wind. The title is a literal translation of the French phrase, “tiré à quatre épingles”, roughly equivalent to the English phrase “dressed to the nines”. Duchamp liked that the literal translation meant nothing in English and had no relation to the object.

In Advance of the Broken Arm (En prévision du bras cassé), 1915. Snow shovel on which Duchamp carefully painted its title. The first piece the artist called a “readymade”. New to America, Duchamp had never seen a snow shovel not manufactured in France. With fellow Frenchman Jean Crotti he purchased it from a stack of them, took it to their shared studio, painted the title and “from Marcel Duchamp 1915” on it, and hung it from a wire in the studio. It was eventually lost. Many years later, a replica of the piece is said to have been mistaken for an ordinary snow shovel and used to move snow off the sidewalks of Chicago.

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.