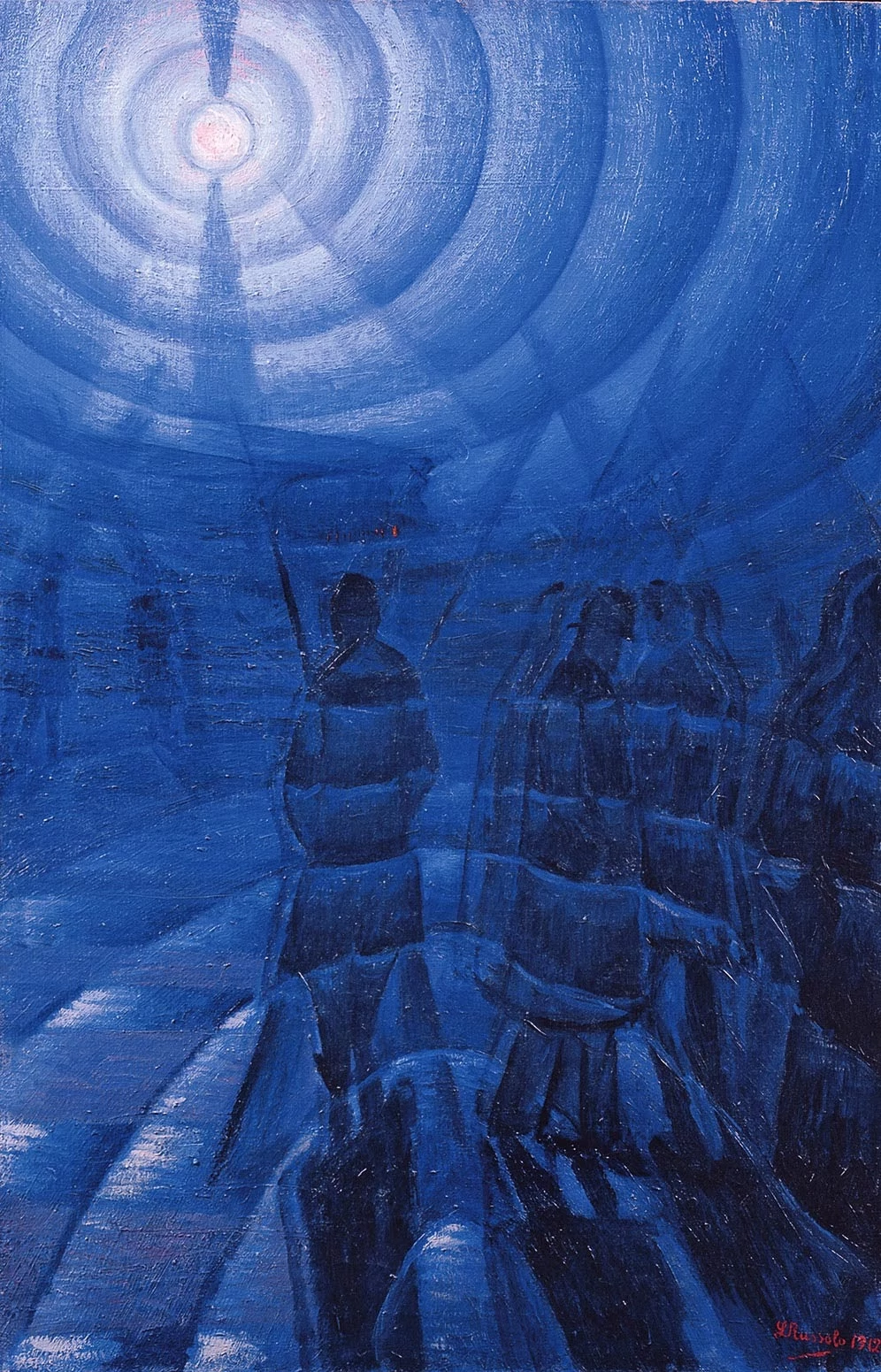

RADIUM AGE ART (1912)

By:

May 5, 2024

A series of notes regarding proto sf-adjacent artwork created during the sf genre’s emergent Radium Age (1900–1935). Very much a work-in-progress. Curation and categorization by Josh Glenn, whose notes are rough-and-ready — and in some cases, no doubt, improperly attributed. Also see these series: RADIUM AGE TIMELINE and RADIUM AGE POETRY.

RADIUM AGE ART: 1900 | 1901 | 1902 | 1903 | 1904 | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | 1908 | 1909 | 1910 | 1911 | 1912 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | 1922 | 1923 | 1924 | 1925 | 1926 | 1927 | 1928 | 1929 | 1930 | 1931 | 1932 | 1933 | 1934 | 1935 | THEMATIC INDEX.

Hilma af Klint, who from 1908–1911 was caring for her blind, widowed mother and had ceased painting, now returns to her project. Amy Sherlock’s Royal Academy essay claims the following: “When Af Klint returned to her brushes, she was less directly influenced by spirit guidance. Crisper geometric forms emerge in the paintings; her palette is less diluted, her symbols more deliberate.”

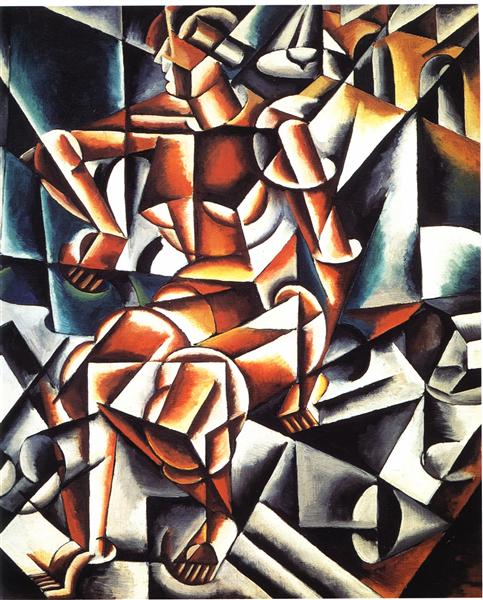

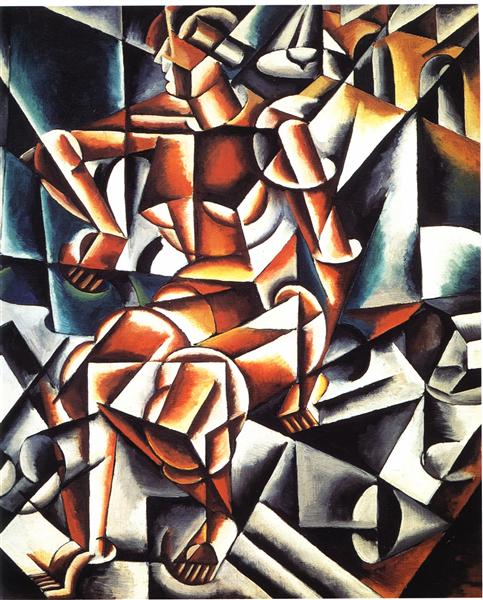

Orphism, Russian Futurism, Cubo-Futurism, Synchromism…

In 1912, Gino Severini persuaded Boccioni and the other Milan-based futurists to visit Paris, where they encountered cubism.

Early on, Robert Delaunay painted in a Neo-Impressionist manner, and from 1909 to 1911, he was briefly associated with Cubism. By 1912, however, he became increasingly preoccupied with the dynamics of color relationships and made his first “disc” painting; he deployed the motif as a symbol for the sun and, ultimately, the universe. Apollinaire described this new style as “Orphism.” See more below.

In 1912, Hugo Ball meets Wassily Kandinsky, Richard Huelsenbeck, Emmy Hennings.

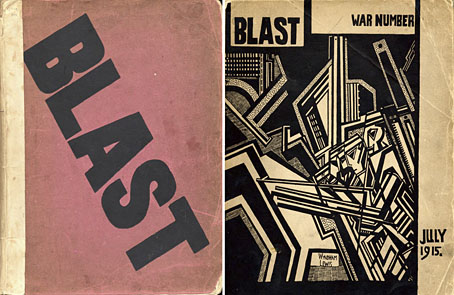

An English artistic movement, the center of which was the journal Blast, Vorticism (like Futurism) relished the advances of the machine age and embraced dynamic change. It is founded c. 1912 by Ezra Pound and the painter Wyndham Lewis.

In 1912, Liubov Popova moves to Paris with fellow painter Nadezhda Udaltsova to study painting at the Académie de la Palette under André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Henri Le Fauconnier, and Jean Metzinger. After returning to Moscow in 1913, she will quickly emerge as one of the primary exponents of Russian Cubo-Futurism.

Marcel Duchamp enters a painting in the Cubists’ 1912 Salon des Indépendants: Nude Descending a Staircase.

In 1912 Duchamp begins writing a (never-completed) book titled A l’Infinitif (also known as The White Box), which references Poincaré’s writings on the fourth dimension, as well as Jouffret’s.

The Salon de la Section d’Or, held October 1912 — the largest and most important public showing of Cubist works prior to World War I — exposed Cubism to a wider audience still. Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, in preparation for the Salon de la Section d’Or, published a major defense of Cubism, resulting in the first theoretical essay on the new movement. In Du Cubisme, Gleizes and Metzinger briefly allude to x rays in their choice of language and in their reference to “Fraunhofer lines,” which were regularly treated in discussions of x-rays and the spectrum. (See AC Doyle’s The Poison Belt, published 1913.) According to Gleizes and Metzinger, Cubism is the product of a new, penetrating mode of vision that utilizes a new kind of revelatory light. The paragraphs following their reference to Fraunhofer rays discuss the new light and color with unmistakable overtones of the expanded vision produced by X rays, claims Henderson.

Du “Cubisme” argues that Cubism is not based on any geometrical theory, but in fact that non-Euclidean geometry corresponded better than classical, or Euclidean geometry, to what the Cubists were doing: “If we wished to relate the space of the [Cubist] painters to geometry, we should have to refer it to the non-Euclidean mathematicians; we should have to study, at some length, certain of Riemann’s theorems.”

It was then that the Cubists taught a new way of imagining light.

According to them, to illuminate is to reveal; to color is to specify the mode of revelation. They call luminous that which strikes the mind, and dark that which the mind has to penetrate. […]

Here are a thousand tints which escape from the prism, and hasten to range themselves in the lucid region forbidden to those who are blinded by the immediate.

This new light, Henderson points out, penetrates like an x ray insread of being reflected from forms (as, e.g., the light of Realism and Impressionism had been).

Apollinaire, writing about the new abstract paintings, in 1912 urges gallery-goers to develop an ability to feel delight in paintings that don’t realistically depict the world. This sort of art can’t be read so easily, perhaps, but one can immerse oneself in it; therefore it stands to painting as we have known it, Apollinaire says, “as music stands to literature.”

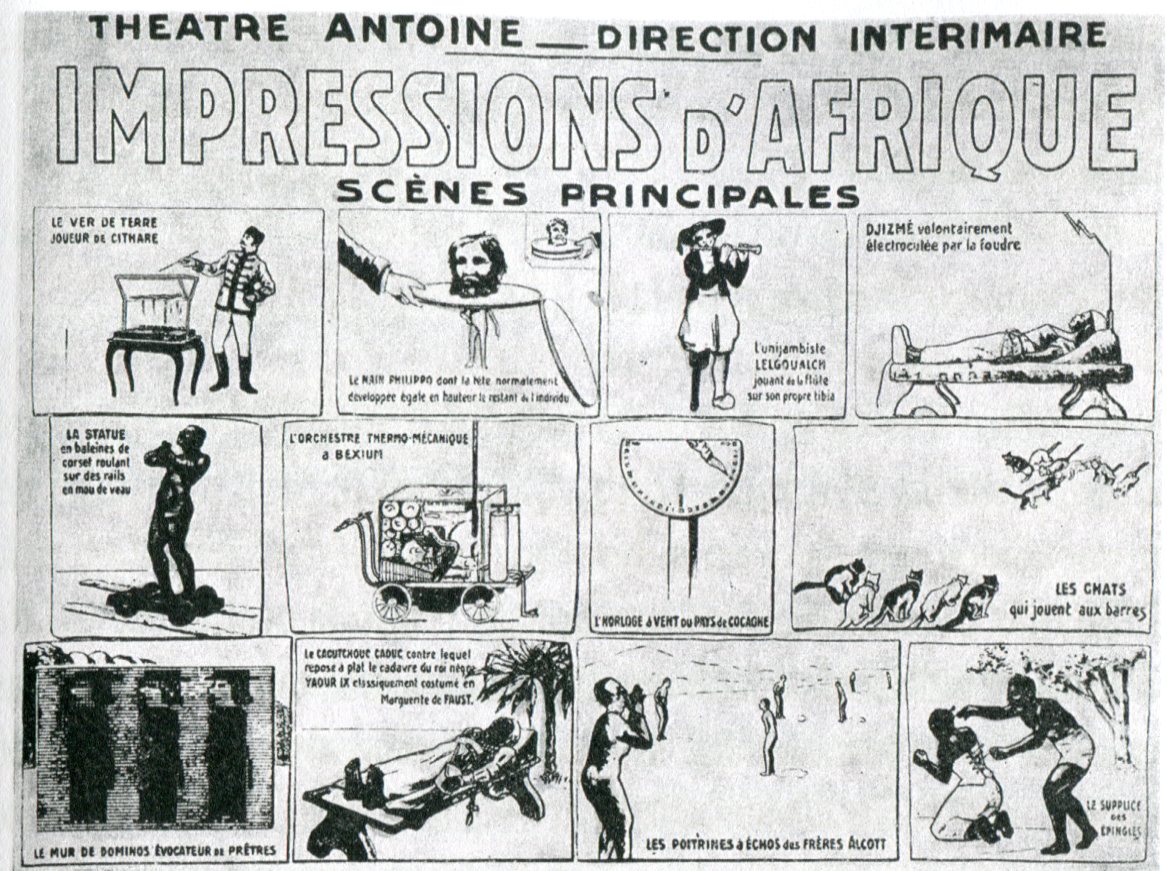

The turning point in Duchamp’s “constant battle to make an exact and complete break” with the techniques and intentions of traditional painting occurs in Paris in 1912, when he attends a performance of Raymond Roussel’s play Impressions d’Afrique (1911–1912, novel version pub;ished 1910) accompanied by Picabia. Roussel’s play includes a number of outré devices, including a “painting machine”. (Cf. Roussel’s proto-sf novel Locus Solus, which also includes an art machine.) Louise Montalescot’s fantastic painting machine in Impressions d’Afrique introduced the concept of a machine that can paint, and consequently the generation of images through chance, which influenced Duchamp, Picabia, Dali and other Surrealist artists.

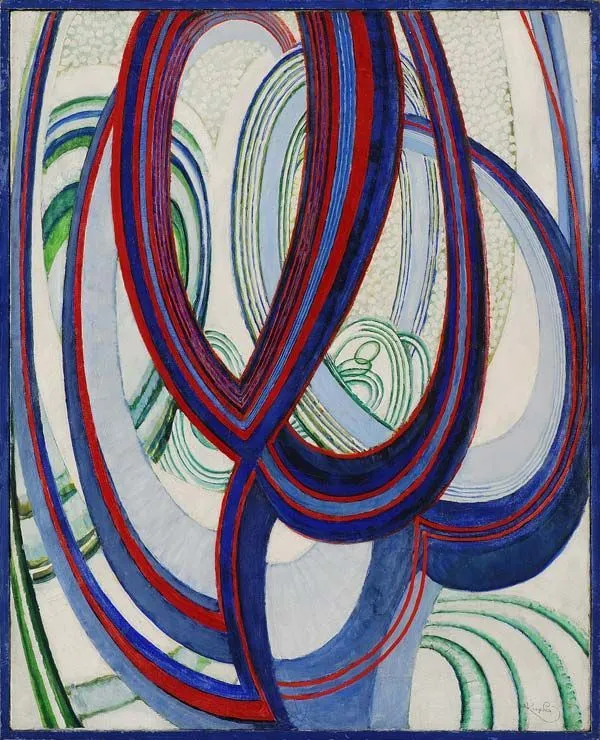

Kupka’s active experimentation with x-ray transparency and the depiction of motion ends in 1912, as he moves towards the realm of total abstraction, painting bold, flat images. See Amorpha, Fugue in Two Colors, below.

See: RADIUM AGE: 1912

Speaking of catastrophe, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land (reissued by the MIT Press’s RADIUM AGE series) appears in 1912.

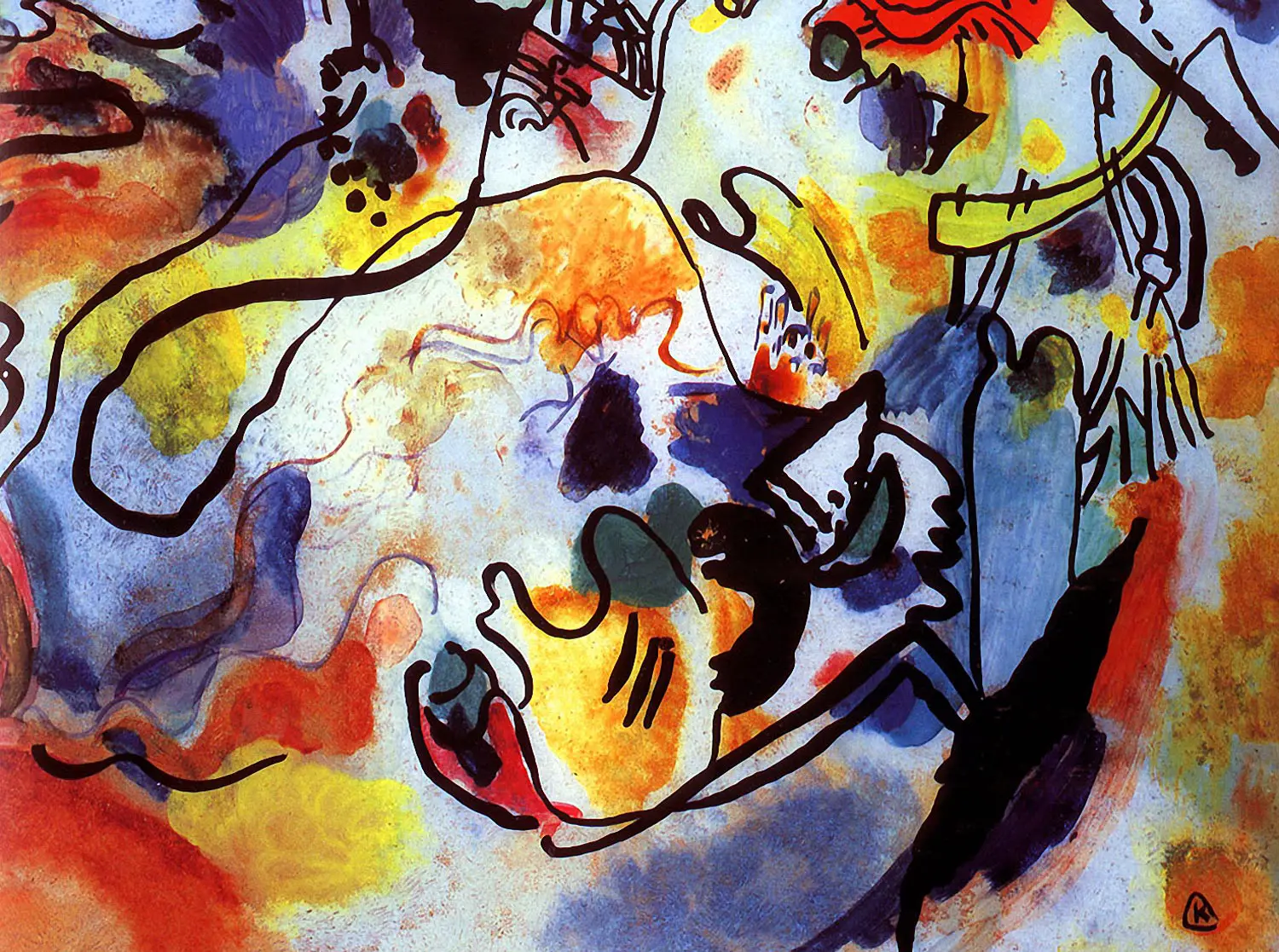

Compare with Kandinsky’s more obviously figurative 1911 painting All Saints Day II. Still detectable (though in a more abstract, and horizontally reversed, fashion) are: the trumpet of an angel in the upper right, the horses pulling the saint’s chariot at upper left, the walls and towers of New Jerusalem on the hilltop. The Leviathan becomes a black blob.

Kandinsky’s “The Last Judgment” returns to the apocalyptic imagery of nineteenth century Romanticism – for examples Turner’s 1800–05 biblical paintings. But Pepe Karmel suggests that Kandinsky’s is joyful apocalypse: “The world is coming to an end, but only so that it can be reborn as an animated cosmos, one in which there is no longer such a thing as dead matter.” A Theosophist, Kandinsky hoped for an immanent cosmic-spiritual transformation.

The devastating scene is one among approximately fifteen paintings from Meidner’s series of apocalyptic landscapes executed between 1912 and 1916.

The subject is taken from the Hebrew Bible, in which God guides the prophet Ezekiel to a valley full of bones and commands him to speak: “There was a noise, and behold a shaking, and the bones came together.” Though Bomberg’s painting style is often associated with vorticism, he didn’t officially join the movement.

Humankind’s confrontation with its own mortality…

From the Guggenheim’s website: “By 1910 many of the artist’s abstract canvases shared a common literary source, the Revelation of Saint John the Divine; the rider [which symbolized Kandinsky’s crusade against conventional aesthetic values and his dream of a better, more spiritual future through the transformative powers of art] came to signify the Horsemen of the Apocalypse, who will bring epic destruction after which the world will be redeemed. In both Sketch for Composition II and Improvisation 28 (second version) Kandinsky depicted — through highly schematized means — cataclysmic events on one side of the canvas and the paradise of spiritual salvation on the other. In the latter painting, for instance, images of a boat and waves (signaling the global deluge), a serpent, and, perhaps, cannons emerge on the left, while an embracing couple, shining sun, and celebratory candles appear on the right.”

Unlike Kupka, Duchamp continues to explore the possible artistic applications of x rays during 1912. The Bride is the culmination of this final phase.

“Duchamp’s Bride is painted in clearly defined, static forms that differ sharply from the fluid, transparent, and often dynamic forms of his X-ray related works of Fall 1911 and Spring 1912. Close to the style of these earlier works is The Passage from Virgin to Bride, which embodies process and fluid motion, as if it were an imaginary x-ray chronophotograph recording internal change and movement (complete with dotted lines)…” (Henderson)

“This is not the realistic interpretation of a bride but my concept of a bride expressed by the juxtaposition of mechanical elements and visceral forms,” Duchamp would later explain. Henderson: “This new preoccupation with the internal organs of the body surely relates to advances in x-ray technology….”

Duchamp’s Bride is reduced to semi-mechanical organs of digestion and reproduction (the gear-toothed womb at lower left).

Duchamp later said that he “first glimpsed the fourth dimension in his work” in his Bride of 1912. Henderson makes the connection to the then-timely notion of clairvoyance: “a four-dimensional being could easily observe the interior of solid, three-dimensional forms, just as x rays had enabled modern man to do.”

Since four-dimensional vision was also frequently linked to “astral vision,” Duchamp’s Bride may unite science and occultism in the quest for invisible reality.

Duchamp’s breakthrough painting La Mariée (Bride) was completed in August 1912. Described by Duchamp as “my concept of a bride expressed by the juxtaposition of mechanical elements and visceral forms,” La Mariée represents a critical step in the growing influence of the machine in Duchamp’s art which would see its ultimate expression in La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (1915-23).

Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, Robert Delaunay, Henri le Fauconnier, Fernand Léger and Marie Laurencin’s 1911 Salon des Indépendants show brought the so-called Section d’Or collective to prominence. The Salon de la Section d’Or, held October 1912, was even more notable… and brought Alexander Archipenko, Joseph Csaky, Roger de La Fresnaye, Juan Gris, and Jean Marchand into their circle. František Kupka and Francis Picabia were in the mix, too, along with the Duchamp brothers, who exhibited under the names of Jacques Villon, Marcel Duchamp and Raymond Duchamp-Villon.

Also see: Hélène Oettingen, Alexander Archipenko, Constantin Brâncuși, Joseph Csaky, Alexandra Exter (or Ekster), Marthe Donas, Pierre Dumont, Natalia Goncharova, Jean Lambert-Rucki, André Lhote, Louis Marcoussis, André Mare, Irène Reno, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, Jeanne Rij-Rousseau, André Dunoyer de Segonzac, Tobeen.

Before its first presentation at the 1912 Salon des Indépendants in Paris, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 was rejected by the Cubists as being too Futurist. (Duchamp would say that his interest in painting it was “closer to the Cubists’ interest in decomposing forms than to the Futurists’ interest in suggesting movement.”) The painting was subsequently shown, and ridiculed, at the 1913 Armory Show in New York City. Dotted lines denote the body’s undulations, and cartoonist’s swirls mark the rhythmic downward tread.

Exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show.

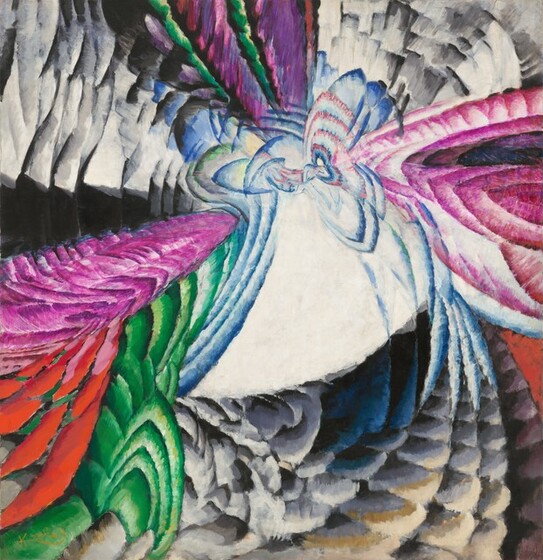

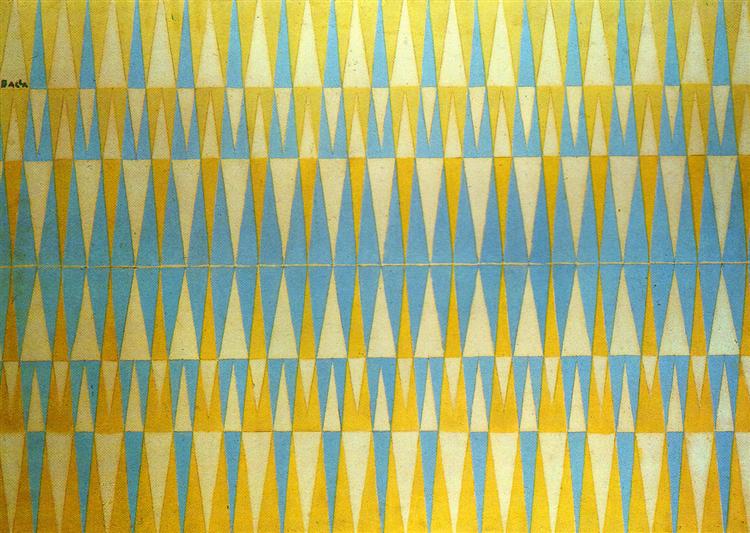

Like Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Kupka wanted his paintings to be the visual equivalent of a type of musical composition in which a short melody is repeated and developed in multi-part counterpoint.

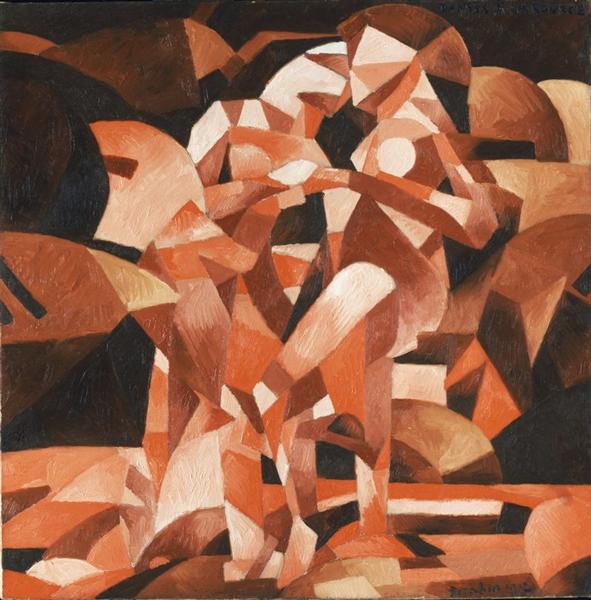

From the book MoMA Highlights: 350 Works from the Museum of Modern Art New York (second edition, 2004), discussing one of several small studies for Amorpha, Fugue in Two Colors:

The painting was exhibited at the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1912, where it provoked general consternation. Whereas Kupka’s original motifs had been inspired by nature, his final gouache studies and the painting itself were totally abstract and distilled to two colors, red and blue. These were intended to represent the interlacing voices of a fugue, in which, as he himself wrote, “the sounds evolve like veritable physical entities, intertwine, come and go.”

Pepe Karmel writes of Amorpha, Fugue in Two Colors that it translates Finnish artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s Ad Astra (1894–96) [shown above], which uses solar-mystical imagery to express a longing for spiritual rebirth, into abstract terms. After noting that the curved blue and red forms derive from Kupka’s 1908–09 studies of a girl with a balloon, Karml argues that here Kupka replaces the solemn adolescent goddess of Ad Astra with “a playful child, juggling planets like toys.”

Apollinaire mentioned the term Orphism in an address at the Salon de la Section d’Or in 1912, referring to Kupka’s Amorpha, as well as to works by Robert Delaunay and others. In his 1913 Les Peintres Cubistes, Méditations Esthétiques Apollinaire described Orphism as “the art of painting new totalities with elements that the artist does not take from visual reality, but creates entirely by himself. […] An Orphic painter’s works should convey an ‘untroubled aesthetic pleasure’, a meaningful structure and sublime significance.”

This website suggests…

Kupka’s “Amorpha” series, painted only a decade after Helge von Koch developed his idea of the snowflake, display a number of features typical to fractal objects. Benoit Mandelbrot himself had observed the fractal nature of Kupka’s work and the very name “Amorpha” is the same word he used 70 years later to describe the objects of his new Geometry. In a 2008 interview to Swiss art curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, Mandelbrot admitted that he became “deeply interested in the paintings of Frantisek Kupka, the first avant – garde Czech painter, because a certain period of his work was clearly “fractal””. A particularly striking example of what Mandelbrot referred to is provided by Kupka’s “Fugue in two colors” (1912), a picture alluding strongly to the connection between music and Mathematics. Here the artist creates an abstract image with regions of increased complexity by repeatedly intertwining roughly elliptic shapes in various scales. The resulting form seems to hint on self similarity and displays, due to some strange coincidence, unmistaken resemblance to regions of the Newton’s fractal described above.

Exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show.

Note from Philadelphia Museum of Art website: “Juan Gris was the only artist included in the 1912 Salon de la Section d’Or who actually used the ideal mathematical proportions of the Golden Section to construct his compositions, as seen in the complex system of grids and geometrical forms that make up this image of a café-terrace dandy. This modern man of taste, complete with top hat and black suit, rests one hand on a chair, while cradling a glass of absinthe in the other. The inclusion of the letters “PIC” and “AP” to the left of the man’s shoulder can be understood as a reference to Picasso, the cocreator of Cubism, and Guillaume Apollinaire, the movement’s fervent critical champion.”

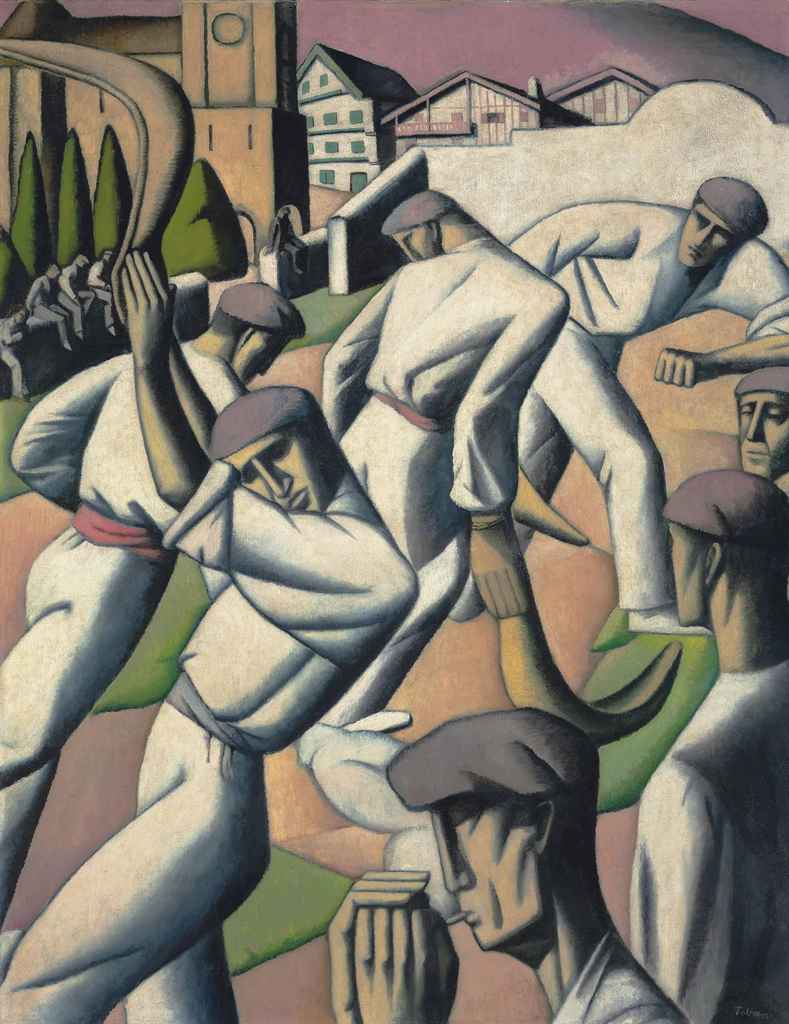

At the Cycle‐Race Track illustrates the final yards of the Paris–Roubaix race, and portrays Charles Crupelandt, the 1912 winner. It’s a photo-finish: a series of frames captured during the final sprint at the end of a race. (One reads that Metzinger’s painting was the first in Modernist art to represent a specific sporting event and its champion. Also see Gleizes’ “Football Players,” 1912–1913; Delauney’s “L’Équipe de Cardiff,” 1913; Boccioni’s “Dynamism of a Cyclist,” 1913; Natalia Goncharova’s “Cyclist,” 1913).

At the Cycle‐Race Track is both a Cubist and a Futurist work. Cubist elements include the reduction of the geometric schema to simplified shapes, and the juxtaposition of rotating planes to define spatial qualities, not to mention printed-paper collage, the incorporation of a granular surface, and multiple perspectives. The choice of a subject in motion (the bicyclist), the suggestion of velocity (motion blur on the wheel spokes), and the fusing of forms in a static picture plane suggest Futurism.

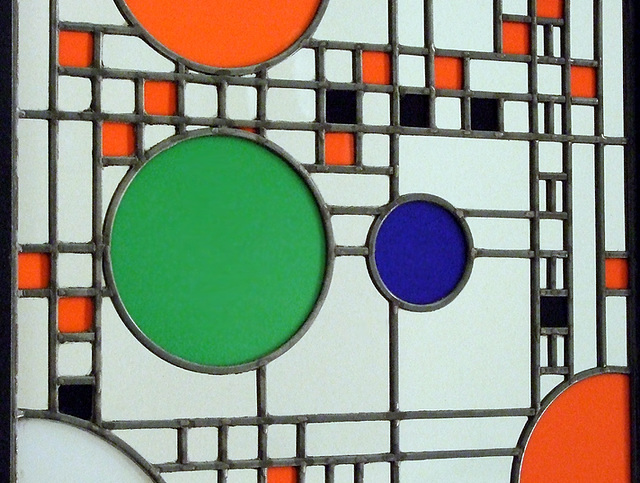

To enliven the interior of a kindergarten he’d architected in the suburbs of Chicago, Frank Lloyd Wright designed stained-glass “clerestory” windows. Each was composed of lively combinations of simple geometric motifs in bright colors. Wright’s belief in the universality of fundamental geometric forms was as much a response to rational methods of modern machine production as an intuitive understanding — shared by many modernist artists – that abstract forms carried shared spiritual values.”

In 1912 Picasso and Braque simplify their orthogonal grid (introduced in 1910) into an open framework of black lines containing isolated patches of color and texture.

See below for an example of this art work used for a science fiction book cover illustration…

Exhibited at the 1913 Armory Show.

Severini combines cubist fragmentation with the curves and colors of Loie Fuller’s abstract dancing.

Picabia’s dance painting — like Severini’s (above) — draws on the formal vocabulary of cubism. But it takes a step further towards abstraction.

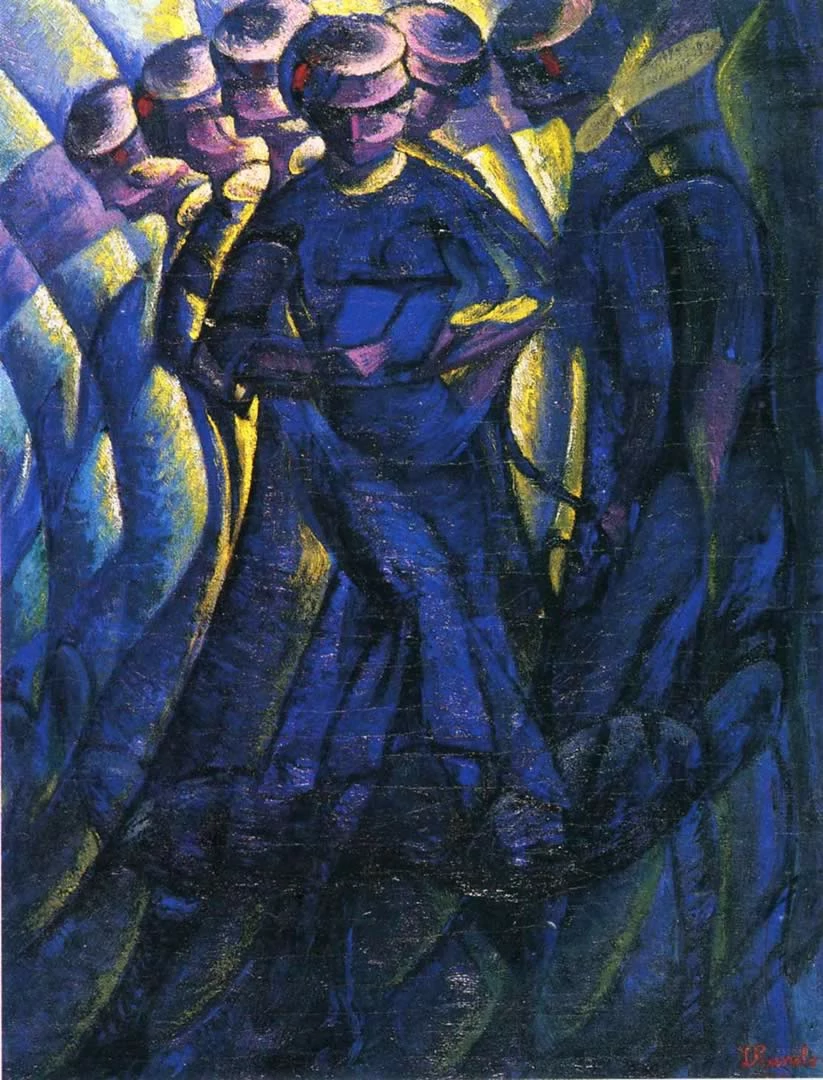

Materia is a portrait of the artist’s mother. The artist merges in a single “simultaneous vision” the optical perception of two distinct subjects, the metropolitan environment and thismother. The profiles of the houses are represented as generating nuclei of wide beams of transparent blue light, which illuminate the “mother” from above.

I’ve also seen it described as a 1911 painting. It showcases the artist’s evolution from a Neoimpressionist style to one more aligned with the ideals of Cubism. The catalog description for “The Street Enters the House” demonstrates Boccioni’s increasing fascination with scientific terminology: It includes lines such as “The principles of Roentgen rays is applied to the work, allowing the personages to be studied from all sides, objects both at the front and the back are in the painter’s memory.”

“Elasticity” depicts a galloping horse through the use of contorted forms, bright colors, and rays of light that create an illusion of speed and motion.

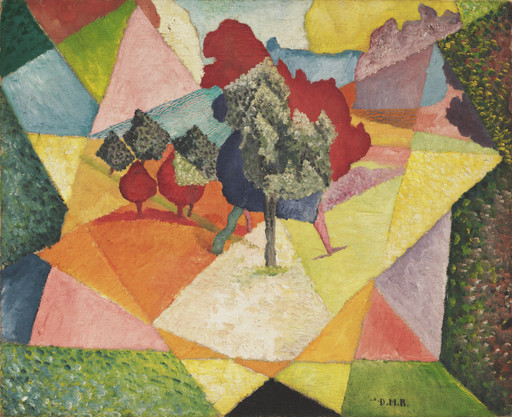

Delaunay’s Simultaneous Windows on the City (1912) is enigmatic… unless you regard it as a Cubist painter’s evolution (or lateral move?) from the Cubists’ analysis of form to an investigation of color and light. The use of chromatic contrast is a primary interest in Simultaneous Windows on the City, and became a central concern of Delaunay’s art. He studied the science of vision and color theory, particularly the writings of M. E. Chevreul and Ogden Rood, which had influenced the Neo-Impressionists in the 19th century. In 1912 he and his wife Sonia developed an approach to painting light by means of color that they called Simultanism.

Absorbing Michel-Eugene Chevreul’s scientific analyses of color — from the 1839 treatise On the Law of the Simultaneous Contrast of Colors — Delauney soon went beyond them into a mystical belief in color, its fusion into unity symbolizing the possibility of harmony in the chaos of the modern world.

From the website Smart History:

The Delaunays were not alone in using the term Simultanism in relation to art. Simultaneity was a popular term with broad significance among avant-garde artists and writers of the time. Generally, it alluded to new concepts of space and time described by early-20th century physicists, such as Einstein, and philosophers, notably Henri Bergson. More specifically, it referred to techniques used by Cubists and Futurists to combine different vantage points into a single “simultaneous” image. Such images were considered a synthesis of memory and perception, and sometimes also a synthesis of many different people’s views.

The Delaunays’ friend, the writer Guillaume Apollinaire, labelled their work “Orphism” or “Orphic Cubism,” and linked it with the work of other artists who were also developing post-cubist styles. Despite Apollinaire’s confusing combination of very different artistic styles and approaches into a single category, the term Orphism has endured. It is sometimes used as a synonym for Simultanism or, more generally, to refer to abstract painting that uses color in a manner comparable to the use of sound and rhythm in music.

The title of this work refers to Sir Isaac Newton, who discovered that the light of the sun is composed of the seven colors of the spectrum: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet. Kupka’s radiant composition incorporates circular bands of vibrating color, including the full range of the spectrum as well as white.

Kupka, as we’ve already seen in this series, ranks as one of the earliest non-representational painters. His series of Newton-Disques (such a sci-fi title) marks the beginning of pure Abstraction. Kupka’s vertical compositions of this date forsake objective forms for what he called “invented elements.”

Kupka was interested in x-ray studies of tissues. It’s been suggested that the transparent, shadow-like forms in his paintings of 1911–1912 may take inspiration from these images (which Theosophists connected with clairvoyant vision) to suggest the interaction of the spiritual and material worlds.

Balla’s nonreferential paintings were informed by his fascination with spiritualism. A fascination he shared with other Italian futurists.

From the Guggenheim: “Delaunay chose the view into the ambulatory of the Parisian Gothic church Saint-Séverin as the subject of his first series of paintings, in which he charted the modulations of light streaming through the stained-glass windows and the resulting perceptual distortion of the architecture. The subdued palette and the patches of color that fracture the smooth surface of the floor point to the influence of Paul Cézanne as well as to the stylistic elements of Georges Braque’s early Cubist landscapes.”

The artist’s attraction to windows and window views, linked to the Symbolists’ use of glass panes as metaphors for the transition from internal to external states, culminated in his Simultaneous Windows series. “One of the artist’s last salutes to representation [the vestigial profile of the Eiffel Tower] before his leap to complete abstraction.”

(The series derives its name from the French scientist Michel-Eugène Chevreul’s theory of simultaneous contrasts of color, which explores how divergent hues are perceived at once.)

NOTES ON ORPHISM

Orphism or Orphic Cubism, a term coined by the French poet Guillaume Apollinaire in 1912, was an offshoot of Cubism that focused on pure abstraction and bright colors, influenced by Fauvism, the theoretical writings of Paul Signac, Charles Henry and the dye chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul. This movement, perceived as key in the transition from Cubism to Abstract art, was pioneered by František Kupka, Robert Delaunay and Sonia Delaunay.

Also known as Simultanism. The Symbolists had used the word orphique in relation to the Greek myth of Orpheus, who they perceived as the ideal artist. For both Apollinaire and the Symbolists who preceded him, Orpheus was associated with mysticism, something that would inspire artistic endeavors. The Orphic metaphor represented the artist’s power to create new structures and color harmonies, in an innovative creative process that combined to form a sensuous experience.

The Orphists were rooted in Cubism but tended towards a pure lyrical abstraction. They saw art as the unification of sensation and color. More concerned with sensation, they began with recognizable subjects, depicted with abstract structures. Orphism aimed to vacate recognizable subject matter by concentrating exclusively on form and color. The movement also strove toward the ideals of Simultanism: endless interrelated states of being.

Francis Picabia and František Kupka also explored Orphism.

From the Guggenheim’s website:

>Orphism emerged in the early 1910s, when the innovations brought about by modern life were radically altering conceptions of time and space. Artists connected to Orphism engaged with ideas of simultaneity in kaleidoscopic compositions, investigating the transformative possibilities of color, form, and motion. Artists include: Robert Delaunay, Sonia Delaunay, Marcel Duchamp, Mainie Jellett, František Kupka, Francis Picabia, and Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso, and by the Synchromists Stanton Macdonald-Wright and Morgan Russell.

We read at WikiArt:

The decomposition of spectral light expressed in Neo-Impressionist color theory of Paul Signac and Charles Henry played an important role in the formulation of Orphism. Robert Delaunay, Albert Gleizes, and Gino Severini, all knew Henry personally. Charles Henry, a mathematician, inventor, esthetician, and intimate friend of the Symbolist writers Félix Fénéon and Gustave Kahn, met Seurat, Signac and Pissarro during the last Impressionist exhibition in 1886. Henry would take the final step in bringing emotional associational theory into the world of artistic sensation: something that would influence greatly the Neo-Impressionists. Henry and Seurat were in agreement that the basic elements of art—the line, particle of color, like words—could be treated autonomously, each possessing an abstract value independent of one another, if so chose the artist. “Seurat knows well” wrote Fénéton in 1889, “that the line, independent of its topographical role, possesses an assessable abstract value” in addition, of course, to the particles of color, and the relation of both to the observer’s emotion. The underlying theory behind Neo-Impressionsim would have a lasting effect on the works produced in the coming years by the likes of Robert Delaunay. Indeed, the Neo-Impressionists had succeeded in establishing an objective scientific basis for their painting in the domain of color. The Cubists were to do so in both the domain of form and dynamics, and the Orphists would do so with color too.

MORE NOTES ON THE FOURTH DIMENSION

In a 1949 essay quoted in Linda Dalrymple Henderson’s “X Rays and the Quest for Invisible Reality in the Art of Kupka, Duchamp, and the Cubists” (1988), Gabrielle Buffet-Picabia recalls the years before WWI as a time characterized by “exploration beyond the realm of the visible and the rational.”

One aspect of the nonperceptible reality that Buffet-Picabia references, writes Dalrymple, is the fourth dimension — i.e., “the popular idea that the three-dimensional world of perception was merely a section of a truer four-dimensional realm, a higher reality to be discovered by sensitive artists or by those possessed of some kind of ‘cosmic consciousness.'” Dalrymple is interested in the influence of fourth-dimensional thinking on modernist art — but also in the influence of Wilhelm Conrad Rontgen’s 1895 discovery of X-rays. In the early years of the century, the fourth dimension and x-rays were linked together in the popular imagination.

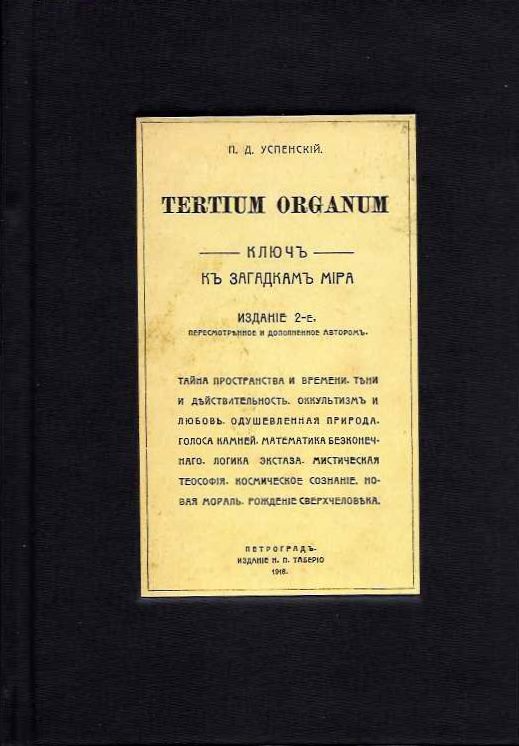

P.D. Ouspensky’s Tertium Organum: The Third Canon of Thought, a Key to the Enigmas of the World, which denies the ultimate reality of space and time and negates Aristotle’s Logical Formula of Identification of “A is A,” published this year also. Architect Claude Bragdon, who was fascinated by fourth dimension theories, would translate the book into English and publish it to acclaim. The book is a pretentious millenarian compendium of occultist clichés of the previous thirty years; however, to many artists, not just Cubists but Surrealists as well, the concept of the fourth dimension symbolized freedom from the stifling constraints of capitalist reality.

Tertium Organum purports to present a new epistomology and a new ontology in accordance with Einstein’s theory of a four-dimensional time continuum. Ouspensky opens his argument by reiterating Kant’s proof that ultimate realities cannot be apprehended by an empirical perception. (Kant had proved that basic phenomena like time and space were only extensions of the individual consciousness.) Assuming that a noumenal world exists, how can we, asks Ouspensky, perceive these ultimate realities? His solution is to turn to consciousness itself, to the intuitive faculty of the mind, for the means whereby these ultimate truths may be perceived. Such reasoning as this only confirmed what Frank himself had decided earlier – that Scientific truth, because it was relative, was inferior to Religious truth, and that scientific or empirical reasoning, when pursued as an end in itself, became destructive and analytical, breaking down the traditional integers of belief and producing nothing to take their place.

Although Ouspensky admits that, as the creatures in Plato’s cave, mortal man can never hope to fully comprehend the world of ultimate reality — “inexpressibility is the sign of truth” — he does make some tentative deductions about this world by a series of analogies. For one thing, it is a world composed of three dimensions plus the fourth dimension. Just as a dog, when he walks past a three-dimensional object, perceives its third dimension (depth) as something fleeting and transitory, so man perceives the fourth dimension (time) as something fleeting and transitory. The fourth dimension is time itself, but since it is a dimension, it is therefore static. Thus the noumenal world is a world of the Eternal Now of Hindu philosophy, a world without past or future. Since there is no duration in such a world, there is no action. And since there is no action, there can be no cause and effect. Likewise, three-dimensional qualities like size and position are nonexistent, and are replaced by subjective feelings of affinity and remoteness. There is no death in this world: everything participates in eternal life. Likewise, there is no individuation, and all share a common self: “Everything is the whole.” Contrary to traditional Platonism, the material world is not illusory — it is only the noumenal world represented imperfectly to our senses. As was previously mentioned, Ouspensky believed that the nature of this noumenal world could be known through mysticism. Any type of mysticism would suffice, he thought, from the extreme asceticism of Yoga to the ecstatic trance of the Dionysian, just as long as the conventional perception of phenomena was disrupted and “an expansion of consciousness” took place.

The book was familiar to many writers in the twenties. Philip Horton reports that the 1923 literary clique — Hart Crane, Gorham Munson, and Jean Toomer — of which Waldo Frank served as patriarch, professedly considered Ouspensky’s book to be their “bible.”

Tertium Organum describes four stages of spiritual development. These are characterized in part by the ability to perceive each of the four spatial dimensions. He described the perception of the fourth and highest stage: “A feeling of four-dimensional space. A new sense of time. The live universe. Cosmic consciousness. Reality of the infinite. A feeling of communality with everyone. The unity of everything. The sensation of world harmony. A new morality. The birth of a superman.”

ALSO

MORE RADIUM AGE SCI FI ON HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SERIES from THE MIT PRESS: In-depth info on each book in the series; a sneak peek at what’s coming in the months ahead; the secret identity of the series’ advisory panel; and more. | RADIUM AGE: TIMELINE: Notes on proto-sf publications and related events from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE POETRY: Proto-sf and science-related poetry from 1900–1935. | RADIUM AGE 100: A list (now somewhat outdated) of Josh’s 100 favorite proto-sf novels from the genre’s emergent Radium Age | SISTERS OF THE RADIUM AGE: A resource compiled by Lisa Yaszek.