THE THIRD DRUG (8)

By:

October 12, 2021

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize E. Nesbit’s 1908 proto-sf story “The Third Drug” for HILOBROW’s readers. (Originally published as by “E. Bland.”) For more Nesbit favorites, visit this page.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8.

“I am alone in the house,” the doctor had said. “No one comes here but me.”

No one would come. He would die there — he, Roger Wroxham — “poor old Roger Wroxham, who was no one’s enemy but his own.” Tears pricked his eyes. He shook his head impatiently and they fell from his lashes.

“You fool,” he said, “can’t you die like a man either?”

Then he set his teeth and made himself lie still. It seemed to him that now Despair laid her hand on his heart. But, to speak truth, it was Hope whose hand lay there. This was so much more than a man should be called on to bear — it could not be true. It was an evil dream. He would awake presently. Or if it were, indeed, real — then someone would come, someone must come. God could not let nobody come to save him.

And late at night, when heart and brain had been stretched almost to the point where both break and let in the sea of madness, someone came.

The interminable day had worn itself out. Roger had screamed, yelled, shouted till his throat was dried up, his lips baked and cracked. No one heard. How should they? The twilight had thickened and thickened till at last it made a shroud for the dead man on the floor by the chair. And there were other dead men in that house; and as Roger ceased to see the one he saw the others — the quiet, awful faces, the lean hands, the straight, stiff limbs laid out one beyond another in the room of death. They at least were not bound. If they should rise in their white wrappings and, crossing that empty sleeping chamber very softly, come slowly up the stairs ——

A stair creaked.

His ears, strained with hours of listening, thought themselves befooled. But his cowering heart knew better.

Again a stair creaked. There was a hand on the door.

“Then it is all over,” said Roger in the darkness, “and I am mad.”

The door opened very slowly, very cautiously. There was no light. Only the sound of soft feet and draperies that rustled. Then suddenly a match spurted — light struck at his eyes; a flicker of lit candlewick steadying to flame. And the things that had come were not those quiet people creeping up to match their death with his death in life, but human creatures, alive, breathing, with eyes that moved and glittered, lips that breathed and spoke.

“He must be here,” one said. “Lisette watched all day; he never came out. He must be here — there is nowhere else.”

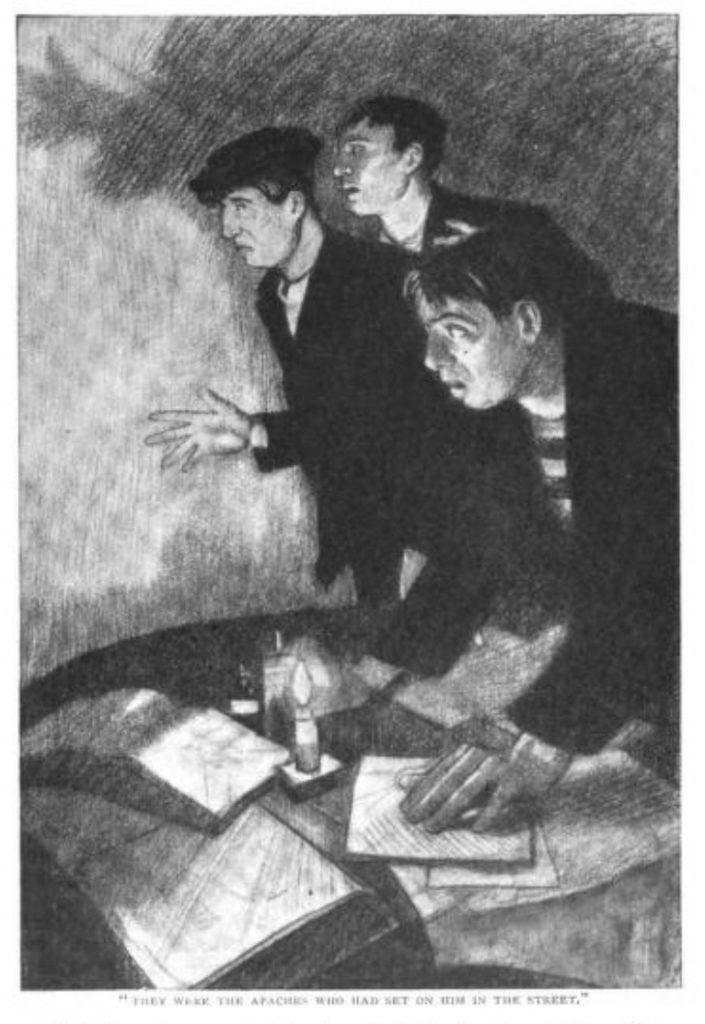

Then they set up the candle-end on the table, and he saw their faces. They were the Apaches who had set on him in that lonely street, and who had sought him here — to set on him again.

He sucked his dry tongue, licked his dry lips, and cried aloud: —

“Here I am! Oh, kill me! For the love of Heaven, brothers, kill me now!”

And even before he spoke they had seen him, and seen what lay on the floor.

“He died this morning. I am bound. Kill me, brothers; I cannot die slowly here alone. Oh, kill me, for pity’s sake!”

But already the three were pressing on each other at a doorway suddenly grown too narrow. They could kill a living man, but they could not face death, quiet, enthroned.

“For the love of Heaven,” Roger screamed, “have pity! Kill me outright! Come back — come back!”

And then, since even Apaches are human, they did come back. One of them caught up the candle and bent over Roger, knife in hand.

“Make sure!” said Roger, through set teeth.

“Nom d’un nom,” said the Apache, with worse words, and cut the bandages here, and here, and here again, and there, and lower, to the very feet.

Then this good Samaritan helped Roger to rise, and when he could not stand, the Samaritan half pulled, half carried him down those many steps, till they came upon the others putting on their boots at the stair-foot.

Then between them the three men carried the other out and slammed the outer door, and presently set him against a gate-post in another street, and went their wicked ways.

And after a time a girl with furtive eyes brought brandy and hoarse muttered kindnesses, and slid away in the shadows.

Against that gate-post the police came upon him. They took him to the address they found on him. When they came to question him he said, “Apaches,” and his variations on that theme were deemed sufficient, though not one of them touched truth or spoke of the third drug.

There has never been anything in the papers about that house. I think it is still closed, and inside it still lie in the locked room the very quiet people; and above, there is the room with the narrow couch and the scattered, cut, violet bandages, and the Thing on the floor by the chair, under the lamp that burned itself out in that May dawning.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.