THE THIRD DRUG (2)

By:

August 29, 2021

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize E. Nesbit’s 1908 proto-sf story “The Third Drug” for HILOBROW’s readers. (Originally published as by “E. Bland.”) For more Nesbit favorites, visit this page.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8.

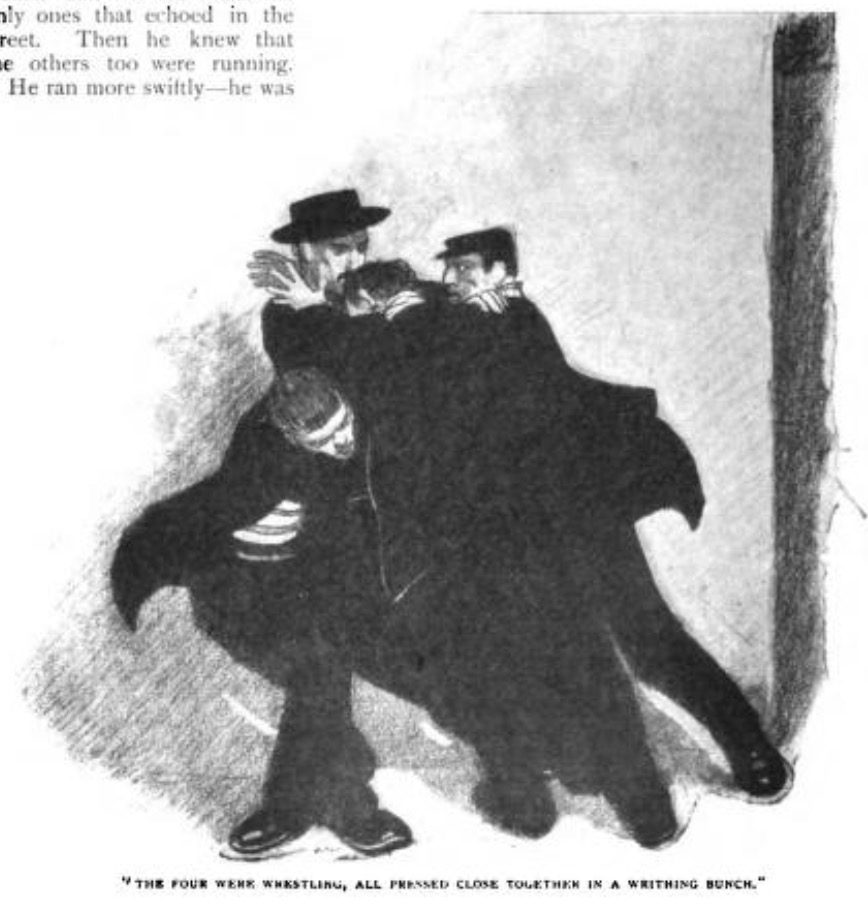

It was then that Roger felt the knife. Its point glanced off the cigarette-case in his breast pocket and bit sharply at his inner arm. And at the sting of it Roger knew, suddenly and quite surely, that he did not desire to die. He feigned a reeling weakness, relaxed his grip, swayed sideways, and then suddenly caught the other two in a new grip, crushed their faces together, flung them off, and ran. It was but for an instant that his feet were the only ones that echoed in the street. Then he knew that the others too were running.

It was like one of those nightmares wherein one runs for ever, leaden-footed, through a city of the dead. Roger turned sharply to the right. The sound of the other footsteps told that the pursuers also had turned that corner. Here was another street — a steep ascent. He ran more swiftly — he was running now for his life — the life that he held so cheap three minutes before. And all the streets were empty — empty like dream-streets, with all their windows dark and unhelpful, their doors fast closed against his need. Only now and again he glanced to right or left, if perchance some window might show light to justify a cry for help, some door advance the welcome of an open inch.

There was at last such a door. He did not see it till it was almost behind him. Then there was the drag of the sudden stop — the eternal instant of indecision. Was there time? There must be. He dashed his fingers through the inch-crack, grazing the backs of them, leapt within, drew the door outside; there was the sound of feet that went away.

He found himself listening, listening, and there was nothing to hear but the silence, and once, before he thought to twist his handkerchief round it, the drip of blood from his hand.

By and by he knew that he was not alone in this house, for from far away there came the faint sound of a footstep, and, quite near, the faint answering echo of it. And at a window high up on the other side of the courtyard a light showed. Light and sound and echo intensified, the light passing window after window, till at last it moved across the courtyard and the little trees threw black shifting shadows as it came towards him — a lamp in the hand of a man.

It was a short, bald man, with pointed beard and bright, friendly eyes. He held the lamp high as he came, and when he saw Roger he drew his breath in an inspiration that spoke of surprise, sympathy, pity.

“Hold! Hold!” He said, in a singularly pleasant voice; “there has been a misfortune? You are wounded, monsieur?”

“Apaches,” said Roger, and was surprised at the weakness of his own voice.

“Your hand?”

“My arm,” said Roger.

“Fortunately,” said the other, “I am a surgeon. Allow me.”

He set the lamp on the step of a closed door, took off Roger’s coat, and quickly tied his own handkerchief round the wounded arm.

“Now,” he said, “courage! I am alone in the house. No one comes here but me. If you can walk up to my rooms you will save us both much trouble. If you cannot, sit here and I will fetch you a cordial. But I advise you to try to walk. That port cochère is, unfortunately, not very strong, and the lock is a common spring lock, and your friends may return with their friends; whereas the door across the courtyard is heavy, and the bolts are new.”

Roger moved towards the heavy door whose bolts were new. The stairs seemed to go on forever. The doctor lent his arm, but the carved banisters and their lively shadows whirled before Roger’s eyes. Also he seemed to be shod with lead, and to have in his legs bones that were red hot. Then the stairs ceased, and there was light, and a cessation of the dragging of those leaden feet. He was on a couch, and his eyes might close.

When next he saw and heard he was lying at ease, the close intimacy of a bandage clasping his arm, and in his mouth the vivid taste of some cordial.

The doctor was sitting in an arm chair near a table, looking benevolent through gold-rimmed pince-nez.

“Better?” He said. “No; lie still, you’ll be a new man soon.”

“I am desolated,” said Roger, “to have occasioned you all this trouble.”

“Not at all,” said the doctor. “We live to heal, and it is a nasty cut, that in your arm. If you are wise, you will rest at present. I shall be honoured if you will be my guest for the night.”

Roger again murmured something about trouble.

“In a big house like this,” said the doctor, as it seemed a little sadly, “there are many empty rooms, and some rooms which are not empty. There is a bed altogether at your service, monsieur, and I counsel you not to delay in seeking it. You can walk?”

Wroxham stood up. “Why, yes,” he said, stretching himself. “I feel, as you say, a new man.”

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.