THE THIRD DRUG (5)

By:

September 21, 2021

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize E. Nesbit’s 1908 proto-sf story “The Third Drug” for HILOBROW’s readers. (Originally published as by “E. Bland.”) For more Nesbit favorites, visit this page.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8.

“What did you see?” the doctor asked. “Tell me!”

“Did you kill them all?” Roger asked back.

“They died — of their own inherent weakness,” the doctor said. “And you saw them?”

“I saw,” said Roger, “the quiet people lying all along the floor in their death clothes — the people who have come in at that door of yours that is a trap — for robbery, or curiosity, or shelter — and never gone out any more.”

“Right,” said the doctor. “Right. My theory is proved at every point. You can see what I choose you to see. Yes; decadents all. It was in embalming that I was a specialist before I began these other investigations.”

“What,” Roger whispered — “what is it all for?”

“To make the superman,” said the doctor. “I will tell you.”

He told. It was a long story — the story of a man’s life, a man’s work, a man’s dreams, hopes, ambitions.

“The secret of life,” the doctor ended. “That is what all the alchemists sought. They sought it where Fate pleased. I sought it where I have found it — in death.”

Roger thought of the room behind the locked door.

“And the secret is?” asked Roger.

“I have told you,” said the doctor, impatiently; “it is in the third drug that life — splendid, superhuman life — is found. I have tried it on animals. Always they became perfect, all that an animal should be. And more, too — much more. They were too perfect, too near humanity. They looked at me with human eyes. I could not let them live. Such animals it is not necessary to embalm. I had a laboratory in those days — and assistants. They called me the Prince of Vivisectors.”

The man on the sofa shuddered.

“I am naturally,” the doctor went on, “a tender-hearted man. You see it in my face; my voice proclaims it. Think what I have suffered in the sufferings of these poor beasts who never injured me. May God bear witness that I have not buried my talent. I have been faithful. I have laid it down all — love, and joy, and pity, and the little beautiful things of life — all, all, on the altar of science, and seen them consume away. I deserve my heaven, if ever man did. And now by all the saints in heaven I am near it!”

“What is the third drug?” Roger asked, lying limp and flat on his couch.

“It is the Elixir of Life,” said the doctor. “I am not its discoverer; the old alchemists knew it well, but they failed because they sought to apply the elixir to a normal — that is, a diseased and faulty — body. I knew better. One must have first a body abnormally healthy, abnormally strong. Then, not the elixir, but the two drugs that prepare. The first excites prematurely the natural conflict between the principles of life and death, and then, just at the point where Death is about to win his victory, the second drug intensifies life so that it conquers — intensifies, and yet chastens. Then the whole life of the subject, risen to an ecstasy, falls prone in an almost voluntary submission to the coming super-life. Submission — submission! The garrison must surrender before the splendid conqueror can enter and make the citadel his own. Do you understand? Do you submit? ”

“I submit,” said Roger, for, indeed, he did. “But — soon — quite soon— I will not submit.”

He was too weak to be wise, or those words had remained unspoken.

The doctor sprang to his feet.

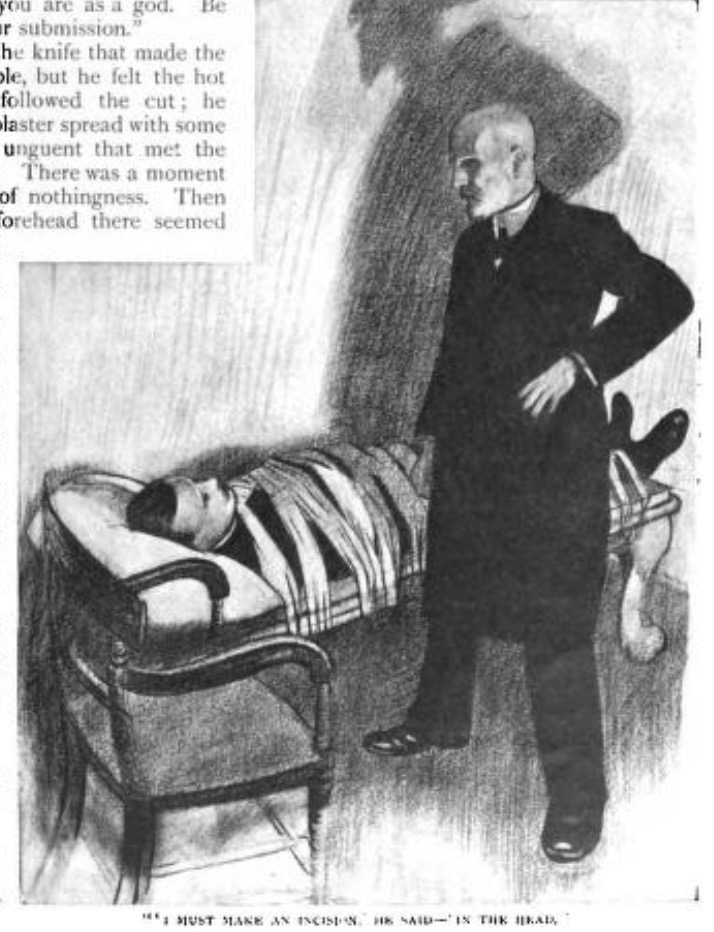

“It works too quickly!” he cried. “Everything works too quickly with you. Your condition is too perfect. So now I bind you.”

From a drawer beneath the bench where the bottles gleamed the doctor drew rolls of bandages — violet, like the haze that had drowned, at the urgence of the second drug, the consciousness of Roger. He moved, faintly resistant, on his couch. The doctor’s hands, most gently, most irresistibly, controlled his movement.

“Lie still,” said the gentle, charming voice. “Lie still; all is well.” The clever, soft hands were unrolling the bandages — passing them round arms and throat — under and over the soft narrow couch. “I cannot risk your life, my poor boy. The least movement of yours might ruin everything. The third drug, like the first, must be offered directly to the blood which absorbs it. I bound the first drug as an unguent upon your knife-wound.’

The swift hands passed the soft bandages back and forth, over and under — flashes of violet passed to and fro in the air like the shuttle of a weaver through his warp. As the bandage clasped his knees Roger moved.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.