THE THIRD DRUG (3)

By:

September 7, 2021

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize E. Nesbit’s 1908 proto-sf story “The Third Drug” for HILOBROW’s readers. (Originally published as by “E. Bland.”) For more Nesbit favorites, visit this page.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8.

A narrow bed and rush-bottomed chair showed like doll’s-house furniture in the large, high, gaunt room to which the doctor led him.

“You are too tired to undress yourself,” said the doctor; “rest — only rest,” and covered him with a rug, snugly tucked him up, and left him.

“I leave the door open,” he said, “in case you should have any fever. Good night. Do not torment yourself. All goes well.”

Then he took away the lamp, and Wroxham lay on his back and saw the shadows of the window-frames cast by the street lamps on the high ceiling. His eyes, growing accustomed to the darkness, perceived the carving of the white paneled walls and mantelpiece. There was a door in the room, another door than the one which the doctor had left open. Roger did not like open doors. The other door, however, was closed. He wondered where it led, and whether it were locked. Presently he got up to see. It was locked. He lay down again.

His arm gave him no pain, and the night’s adventure did not seem to have over set his nerves. He felt, on the contrary, calm, confident, extraordinarily at ease, and master of himself. The trouble — how could that ever have seemed important? This calmness — it felt like the calmness that precedes sleep. Yet sleep was far from him. What was it that kept sleep away? The bed was comfortable — the pillows soft. What was it? It came to him presently that it was the scent which distracted him, worrying him with a memory that he could not define. A faint scent of — what was it? Perfumery? Yes — and camphor — and something else — something vaguely disquieting. He had not noticed it before he had risen and tried the handle of that other door. But now —— He covered his face with the sheet, but through the sheet he smelt it still. He rose and threw back one of the long French windows. It opened with a click and a jar, and he looked across the dark well of the courtyard. He leaned out, breathing the chill pure air of the May night, but when he withdrew his head the scent was there again. Camphor — perfume — and something else. What was it that it reminded him of? He had his knee on the bed-edge when the answer came to that question. It was the scent that had struck at him from the darkened room when, a child, clutching at a grown-up hand, he had been led to the bed where, amid flowers, something white lay under a sheet — his mother they had told him. It was the scent of death, disguised with drugs and perfumes.

He stood up and went, with carefully controlled swiftness, towards the open door. He wanted light and a human voice. The doctor was in the room upstairs; he ——

The doctor was face to face with him on the landing, not a yard away, moving towards him quietly in shoeless feet.

“I can’t sleep,” said Wroxham, a little wildly; “it’s too dark and ——”

“Come upstairs,” said the doctor, and Wroxham went.

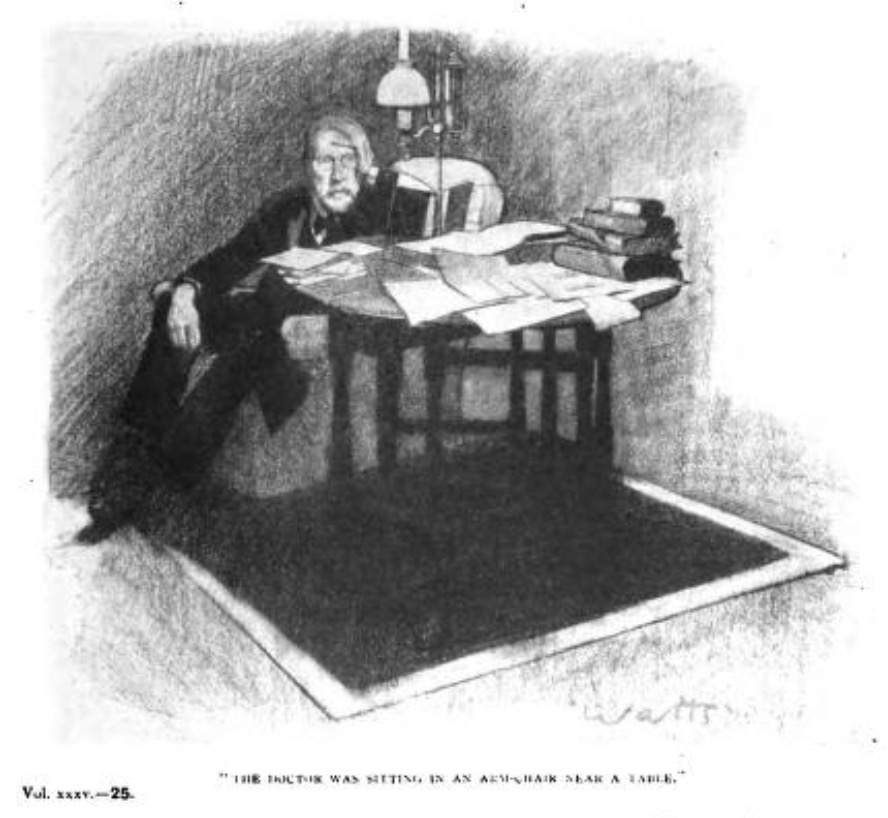

There was comfort in the large, lighted room. A green shaded lamp stood on the table.

“What’s behind that door,” said Wroxham, abruptly — “that door downstairs?”

“Specimens,” the doctor answered; “preserved specimens. My line is physiological research. You understand?”

So that was it.

“I feel quite well, you know,” said Wroxham, laboriously explaining — “fit as any man — only I can’t sleep.”

“I see,” said the doctor.

“It’s the scent from your specimens, I think,” Wroxham went on; “there’s something about that scent.”

“Yes,” said the doctor.

“It’s very odd.” Wroxham was leaning his elbow on his knee and his chin on his hand. “I feel so frightfully well —— and yet there’s a strange feeling —— ”

“Yes,” said the doctor. “Yes, tell me exactly how you feel.”

“I feel,” said Wroxham, slowly, “like a man on the crest of a wave.”

The doctor stood up.

“You feel well, happy, full of life and energy — as though you could walk to the world’s end, and yet ——”

“And yet,” said Roger, “as though my next step might be my last — as though I might step into a grave.”

He shuddered.

“Do you,” asked the doctor, anxiously — ” do you feel thrills of pleasure —something like the first waves of chloroform — thrills running from your hair to your feet?”

“I felt all that,” said Roger, slowly, “downstairs before I opened the window.”

The doctor looked at his watch, frowned, and got up quickly. “There is very little time,” he said.

Suddenly Roger felt an unexplained thrill of pain.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.