10 Best Adventures of 1984

By:

January 14, 2020

Thirty-six years ago, the following 10 adventures from the Eighties (1984–1993) were first serialized or published in book form. They’re my favorite adventures published that year.

Please let me know if I’ve missed any adventures from this year that you particularly admire. Enjoy!

- Martin Amis‘s picaresque/crime adventure Money. Subtitled A Suicide Note, Amis’s fifth novel concerns the misadventures of John Self, a vile British director of TV ads who heads to New York to shoot a film. Set in the summer of 1981, with the Brixton riots and the royal wedding going on in the background, it’s a novel about how pear-shaped and porno-fied American culture has become, and how Americanized British culture has become. (Self eats a lot of fast food, with monikers like Rumpburger, Big Thick Juicy Hot One, and Long Whopper.) Everything goes wrong with the shoot — one begins to suspect that Fielding Goodney, the producer, is for some reason intentionally sabotaging things. But Self doesn’t need any help getting into trouble. His eating, drinking, pill-popping, smoking, whoring, gambling, shitting, and — above all else — spending spiral out of control. As with London Fields, Amis’s 1989 murder mystery, Money is a blackly comic puzzle — the twisted lineaments of which we cannot begin to comprehend until the novel’s surprise denouement. Nothing is as it seems. An arrogant character, a novelist named Martin Amis who lives nearby in Notting Hill, appears as a kind of confidant in Self’s final breakdown; Self himself is not himself! What he is, is: misanthropic, misogynistic, and quite amusing. He’s a Kingsley Amis character without any restraints. Fun facts: Time Magazine named Money one of the top 100 novels of all time. It was adapted as a two-part TV series — starring the excellent Nick Frost as John Self — by the BBC in 2010.

- William Gibson‘s Diamond Age sci-fi adventure Neuromancer. Gibson may not have invented “cyberspace,” prototypes of which we can find in James Tiptree Jr.’s The Girl Who Was Plugged In (1973) and John Brunner’s The Shockwave Rider (1975), but he coined the term; and Neuromancer — which describes cyberspace as “a consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts […] A graphic representation of data abstracted from banks of every computer in the human system […] Lines of light ranged in the nonspace of the mind, clusters and constellations of data” — single-handedly popularized the concept. Case (a computer hacker), Molly Millions (a cyborg mercenary), and Peter (a thief and illusionist) are hired by a mysterious employer to commit a series of virtual-reality crimes that eventually lead to their assault on an orbiting data-fortress that houses two vastly powerful AIs. The plot is thrilling, but it’s the novel’s endstage-of-capitalism context — a near-future dystopian world dominated by corporations and inescapable technology, Chandler-esque noir cityscapes populated by colorful lowlifes, a virtual reality global network known as “the Matrix” — that earned it a richly deserved cult following. It’s an extraordinary debut novel, well worth revisiting. Fun facts: Neuromancer was the first novel to win the Nebula, the Philip K. Dick, and the Hugo Awards. Its sequels are Count Zero (1986) and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988). Tim Miller, who made the Deadpool movie, has signed on to direct the film adaptation, currently in development.

- Stan Sakai’s talking-animal ronin comic Usagi Yojimbo (serialized 1984 – present). Miyamoto Usagi, a masterless samurai (that is to say, a ronin), roams a civil war-plagued 17th-century Japan, contending and cooperating with anthropomorphic cats, snakes, and other creatures — such as the evil Lord Hikiji, a rhino bounty hunter, a blind sword-pig, and the occasional ninja mole. Sakai, a Japanese-born American cartoonist who formerly worked on Sergio Aragone’s Groo, inserts his perapatetic rabbit yojimbo (bodyguard) into fanciful Japanese myths and legends… with plenty of references to his favorite samurai movies. I wasn’t attracted to Usagi Yojimbo when it first appeared, I think primarily because it was in black and white — and it seemed cutesy. Now, however, I appreciate its blend of humor, violence, and heartfelt emotion. The landscapes are beautifully rendered, the architecture and costumes appear to be faithfully rendered, the mythical creatures are fun, and the serial installments in Usagi’s musha shugyō (warrior’s pilgrimage) is gripping. Over the years, Sakai has given us long extended storylines and a few novel-length narratives; on the whole, I prefer to episodic stories — which are the most like a Kurosawa movie. Fun facts: Miyamoto Usagi, whom Sakai based partially on the famous swordsman Miyamoto Musashi, first appeared in the 1984 anthology Albedo Anthropomorphics in 1984, before landing his own series in 1987. The Usagi Yojimbo saga has been pubished by Fantagraphics, Mirage, and Dark Horse. Usagi, by the way, is Japanese for “rabbit.”

- Ross Thomas’s political thriller Briarpatch. Benjamin “Pick” Dill, a Washington, DC-based investigator working for a U.S. Senate investigations subcommittee, returns to his (unnamed, Oklahoma City-like) hometown when his sister Felicity, a homicide detective, is killed in a car bombing. While he’s there, Dill is also tasked with taking a deposition from his boyhood friend Jake Spivey, an ex-CIA op who — in the aftermath of the Vietnam War — made an illicit fortune as an arms dealer. Spivey, it seems, is the only person who can take down Clyde Brattle, another ex-Agency man who is suspected of having committed crimes against the state. Dill discovers evidence suggesting that his sister was a crooked cop, but he doesn’t believe it. His investigation brings him into contact with his sister’s friend Anna Maud Singe, a beautiful lawyer, who is convinced of Felicity’s innocence; and with Felicity’s boss, the chief of detectives, who is not so sure. The titular briarpatch is Spivey’s mansion, which is guarded by a trio of Mexican thugs. Several homicides ensue. Who’s to blame — the friendly ex-spook, the sinister ex-spook, or someone else? Fun facts: Briarpatch was awarded the 1985 Edgar for Best Novel. The USA Network has adapted the novel as a TV show, which will debut in February 2020; it stars Rosario Dawson, cast as the returning investigator.

- Robin McKinley’s Damar YA fantasy adventure The Hero and the Crown. Aerin, heroine of this prequel to The Blue Sword (1982), isn’t your usual princess. She’s considered ugly — because she’s tall, awkward, fair-skinned, redheaded; other inhabitants of Damar, a remote region of an empire called Homeland, are bronzed and black-haired. Worse, she is the only young member of the royal family whose magical Gift has never manifested. Still, her cousin Tor — who is heir to the throne — is in love with her, though she doesn’t realize it. She trains herself, secretly and stubbornly, to become a warrior; and she develops a balm that protects its user against flame — which will come in handy when she heads out, on her lame but trusty steed Talat, to kill a few of the minor dragons who’ve infested Damar. Left behind when Damar’s armed forces march to battle against their Northern neighbors, Aerin must deal with a great dragon, the dread Maur. Meanwhile, her dreams are haunted by Luthe, the pale-skinned mage of the mountains, the Edward to Tor’s Jacob. Whom will she choose? Fun facts: Winner of the Newbery Medal. Short stories set in Damar include: “The Healer” (1982), “The Stagman” (1984), “The Stone Fey” (1998), and “A Pool in the Desert” (2004).

- Octavia E. Butler’s Patternist sci-fi adventure Clay’s Ark. In the year 2021, a doctor named Blake and his teenage daughters are captured by Eli Doyle, the only survivor of Clay’s Ark, a spaceship that — upon its return from the first manned mission to Proxima Centauri — has crash-landed in southeastern California’s Mojave Desert. Infected with an alien microorganism that gives him heightened sensory and physical powers, but which compels him to transmit the infection to others via sexual contact, Eli has isolated himself on an isolated ranch… where he and others whom he’s captured (all of whom have been altered, by the microorganism, in ways that allow them to survive and thrive) are raising their sphinx-like offspring — intelligent quadruped mutants who perceive uninfected humans as food, and who can spread the microorganism through their bite. Society, meanwhile, has devolved into armed enclaves, marauding “car families,” and other post-apocalyptic phenomena. Blake and his daughters must decide whether to resign themselves to living within Eli’s enclave… or escape, and risk not only being captured by even worse predators, but aso creating an uncontrollable epidemic that could forever transform humankind. Though written last, Clay’s Ark is chronologically the third in the Patternist series. Fun facts: With the exception of Kindred in 1979, all of Butler’s earlier books are set in the Patternist universe. The first Patternist installment, Patternmaster, was published in 1976.

- Alan Moore’s Saga of the Swamp Thing comic series (1984–1987). The Swamp Thing — an anthropomorphic mound of vegetable matter, originally a scientist named Alec Holland — first appeared in House of Secrets in 1971, before getting his own series. In 1982, DC Comics revived the moribund series, attempting to capitalize on the Wes Craven film of the same name; however, the series was headed for cancelation when Alan Moore — then a relatively unknown writer for the British comics magazine 2000 AD — was given free rein to revamp the character. Moore’s Swamp Thing is not a transformed human, but a monster — albeit one which has absorbed Alec Holland’s knowledge, memories, and skills. What’s more, this Swamp Thing is the latest in a long line of designated defenders of “the Green,” an elemental community connecting all plant life on Earth. Moore’s run on the title — the first mainstream comic book series to completely abandon the Comics Code Authority — is a horror story on a semi-mythic level. Swamp Thing Annual #2, during which the Swamp Thing encounters the occult DC characters Deadman, the Phantom Stranger, the Spectre, and Etrigan in the Underworld, is modeled on Dante’s Inferno. Moore has a lot of fun, here: Human/plant romance and intercourse; vampires, zombies, and a werewolf; and a crossover with Walt Kelly’s Pogo and his swamp-dwelling friends. Fun facts: In the wake of Moore’s run on Swamp Thing and his Watchmen series, the visionary DC editor Karen Berger recruited Neil Gaiman, Dave McKean, Peter Milligan, and Grant Morrison, among other artists later described as the “British Invasion.” Characters spun off from Moore’s Swamp Thing — e.g., The Sandman, Hellblazer, The Books of Magic — gave rise to DC’s Vertigo comic book line.

- K.W. Jeter’s Diamond Age sci-fi adventure Dr. Adder. Jeter’s debut novel was written in 1972, the year that Pink Flamingos — John Waters’s trashy, hyperbolic, violent movie that notoriously features a live chicken being crushed between copulating weirdos — was released. Dr. Adder wasn’t published until 1984, because of the weird sex (it begins in a mutated-chicken-whore brothel managed by our protagonist, the disaffected Limmit) and hyperbolic violence, at which point it gained a cult following. It has been hailed as perhaps the first cyberpunk novel, which to me suggests that John Waters is the godfather of cyberpunk! The titular Dr. Adder is a Doctor Moreau-like surgeon who dwells in the ruins of future Los Angeles, reshaping the body parts of Orange County’s perverted teen runaways. Adder has become an unlikely symbol of freedom to LA and OC denizens, who are oppressed by the puritanism of John Mox, a financial titan and would-be ayatollah — whose daily TV sermons are opposed by the freaky ramblings of DJ KCID, a pirate-radio operator. What does the Internet-like space occupied by Mox and KCID have to do with the Interface, LA’s seediest neighborhood? Once a WMD-toting Limmit comes to town, we’ll find out. Dr. Adder is often funny, but it’s also misogynistic and disturbing. Fun facts: The character KCID is modeled after Jeter’s friend, the legendary sci-fi author Philip K. Dick. Dick contributed an Afterword to Dr. Adder, in which he claimed that had its publication not been delayed, its impact on science fiction would have been enormous.

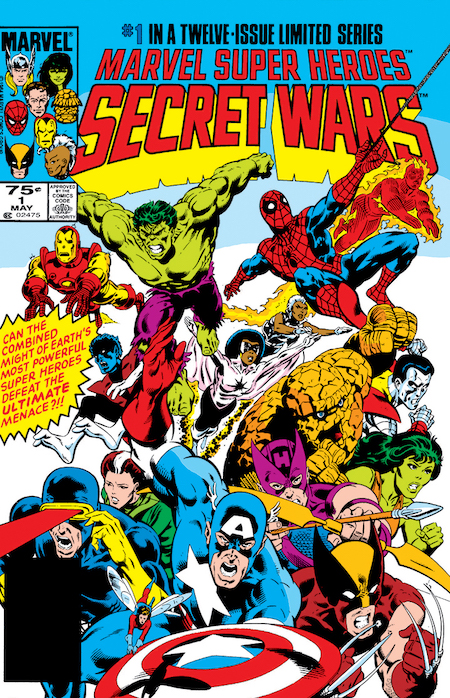

- Jim Shooter, Mike Zeck, and Bob Layton’s Marvel Super Heroes Secret Wars (Marvel Comics, serialized 1984–1985). Secret Wars is a twelve-issue crossover limited series, written by Marvel Comics’ editor-in-chief Jim Shooter, with art by Mike Zeck and Bob Layton. Fascinated by the presence of super-powered beings on Earth, a cosmic entity known as the Beyonder kidnaps members of the Avengers (including Captain America, Iron Man, She-Hulk, and Thor), the Fantastic Four (Human Torch, Mister Fantastic, The Thing), and the X-Men (including Nightcrawler, Rogue, Storm, Wolverine), as well as Spider-Man, Spider-Woman, and the Hulk, and teleports them to “Battleworld,” a purpose-built arena stocked with alien weapons and technology. There, he pits the superheroes against Doctor Doom, Doctor Octopus, the Enchantress, Kang the Conqueror, Klaw, the Lizard, Molecule Man, Ultron, and other supervillains — including the newly minted villainesses Titania and Volcana. A thrilling, goofy battle royale ensued, with sub-plots: Spider-Man finds and wears the black costume for the first time; Colossus breaks up with Kitty Pryde; etc. The scenario, which is reminiscent of Marion Zimmer Bradley’s now-obscure 1974 sci-fi novel Hunters of the Red Moon, is considered one of the first “Event Comics” ever, and is considered second only to DC Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths event in terms of its significance. Fun facts: Aware that Mattel was interested in licensing Marvel’s characters, Jim Shooter proposed staging the Secret Wars event as a platform around which Mattel could build a theme. It was Mattel — which would release three waves of action figures, vehicles, and accessories in the Secret Wars toyline from 1984 to 1985 — who suggested the word “secret” be included in the title.

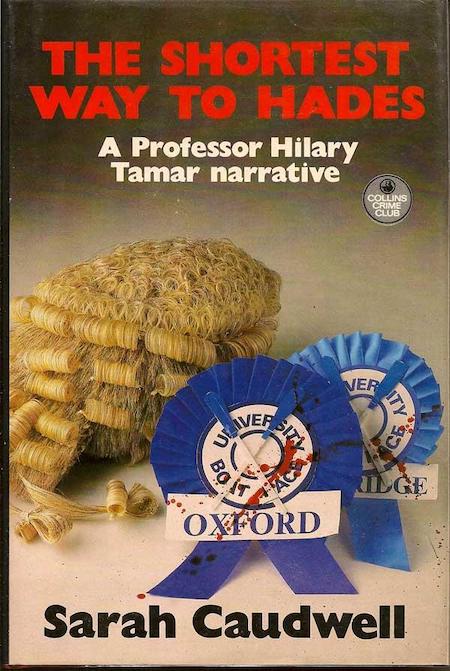

- Sarah Caudwell’s Hilary Tamar crime adventure The Shortest Way to Hades. In her second and most entertaining outing, Hilary Tamar, a snobbish Oxford professor of Legal History, is called in by former students — Cantrip, Ragwort, Selina and Julia, the junior members of a London legal firm — to investigate the drowning death of a young woman. The victim, it seems, had stood in the way of her beautiful cousin Camilla’s inheritance. Was she murderered? Tamar flies to the Greek island of Corfu, where the drowning took place; the Edmund Crispin-like farcical murder mystery involves not only arcane aspects of British inheritance law but erudite interpretations of Greek mythology. The cool-headed Selena narrates much of the adventure. At one point, finding herself at an orgy, Selena instead produces a copy of Pride and Prejudice and begins to read it. The book is drily witty, never more so than when it reverse gender stereotypes; for example: “Young men … like to be thought of as people, not as mere physical objects: you should therefore begin by seeming to admire their fine souls and splendid intellects and showing a warm interest in their hopes, dreams and aspirations.” Fun facts: Sarah Caudwell was the pseudonym of barrister and insurance exec Sarah Cockburn, who wrote three other Hilary Tamar novels — Thus Was Adonis Murdered, The Sirens Sang of Murder, The Sibyl in Her Grave.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES (in progress) | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | NOTES ON 21st-CENTURY ADVENTURES.