IMAGINARY FRIENDS (10)

By:

September 29, 2017

One in a series of ten posts reprinting HILOBROW friend Alexandra Molotkow’s profiles of figures who’ve loomed large in her personal pantheon.

Originally published in the New York Times Magazine (August 9, 2013).

If his life had gone just a bit differently, Curt Boettcher might be remembered as another Brian Wilson. Ezra Miller would play him in the biopic, and his albums would be ubiquitous and fairly priced. As it stands, Boettcher, a pop-music producer whose heyday was the late ’60s, now survives in rock history mostly as a liner-note credit. He never made it big, but he enjoys a godlike status among music fans for whom obscurity is more enticing than fame.

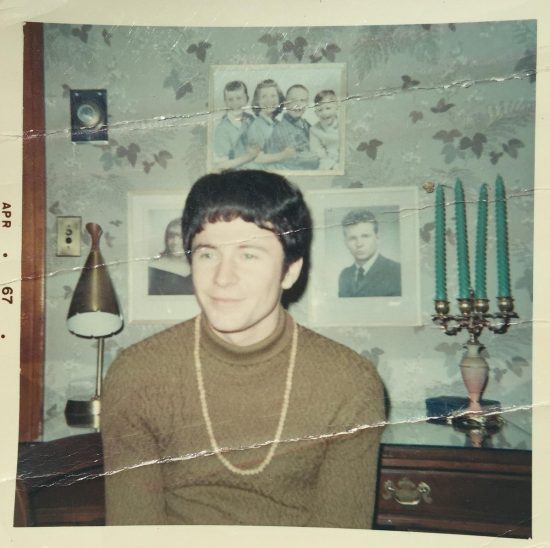

Boettcher began his career as a golden boy. In the early ’60s, barely out of his teens, he released two albums with a folk act called the GoldeBriars. By 22, having landed in Los Angeles, he was producing hits for Tommy Roe and the Association, making him an architect of some of the most beloved and parodied sounds of the era. As a vocal arranger, he created cat’s-cradle harmonies and clarified them to an atmosphere; as a producer, he set bubblegum in resin, laying track after track until featherweight tunes were as dense as paperweights. His voice was often somewhere in the mix, and it matched his face, which was elfin and pretty. He had “a mouth that smiled on the edges all the time,” says his former wife, Claudia Ford.

His biggest break came when Gary Usher, a staff producer for Columbia Records, heard him recording in another studio down the hall. “I’m over at Studio Three West with Brian Wilson,” Usher said in a 1988 interview. “All of a sudden, I heard a sound, and the instant I heard it, I froze, just like someone had thrown a bowling ball at me… And Brian looked at me, I looked at Brian, and we both said simultaneously, ‘What is that?’” The two raced down the hallway to find “this little kid with an earring.” Usher said he was “light years” ahead of Wilson, and would persuade Columbia to hire him.

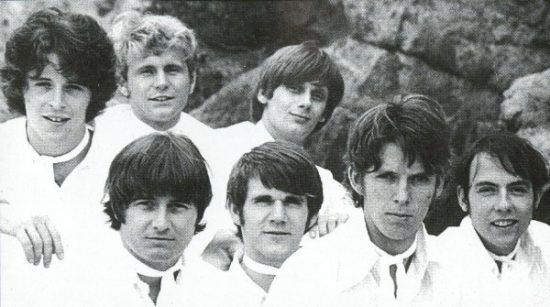

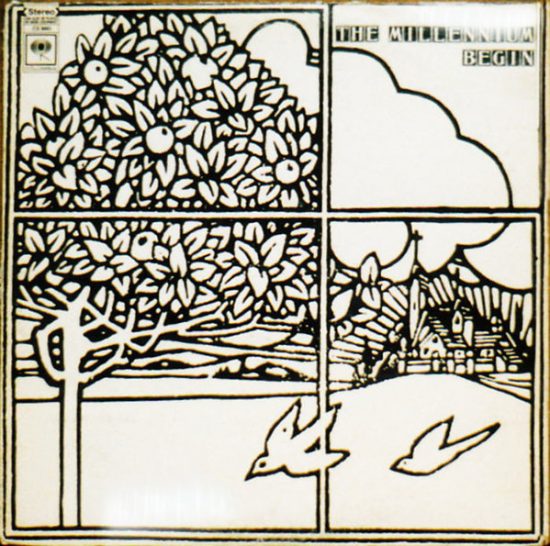

The two collaborated on an album called Present Tense under the name Sagittarius, and by 1968 Boettcher had put together a seven-piece group of his own called The Millennium. He had major creative ambitions, a spiritual mission, and an ego: “We are dropping pebbles,” he said. “Upon this rock I shall build my church and we’re just all getting together and blowing one another’s cool.” Thanks to Usher’s patronage, Columbia gave them plenty of leeway; the band’s debut album, Begin, is said to have cost more than $100,000, and been the most expensive rock record the label had ever produced.

Those who heard Begin loved it. But not many did; it flopped spectacularly. The Millennium wouldn’t play live. Their singles missed the U.S. charts. Columbia lost interest, internal tensions broke up the band, and Boettcher’s career never fully recovered. In 1972 he released a solo record, but it was a commercial failure. He recorded an album with a group called California, an attempt to bridge the California sound with disco, but it was shelved. In 1979, he oversaw a 10 ½-minute disco remix of the Beach Boys’ “Here Comes the Night,” which didn’t go over well with fans.

It’s tempting to give Boettcher a messianic cast — the world wasn’t ready for his genius — but I think the truth is sadder, and more mundane. He may have been a genius, but he wasn’t a player, and he had terrible luck, although he never stopped trying. In the ’80s, he tested positive for HIV. In 1986 his air conditioner sprung a leak, and his carpets developed mildew. About a year after that, having developed a lung infection, he checked himself into a hospital. There was no lawsuit, but Claudia Ford said that a blood vessel was clipped in his lung during a biopsy, and the medical staff, fearful of his positive status, avoided him while he bled out. Boettcher died on June 14, 1987, at the age of 43.

At the time of Boettcher’s death, at least one person was searching for him: Dawn Eden, an 18-year-old student at New York University. As he was entering the hospital, Eden was calling an acquaintance in LA to ask if he’d look up Boettcher’s number in the phone book — the friend refused, saying that “nobody who’s anybody” would have a listed number. Years later, she learned he’d been listed up until his death. Eden, raised mostly by her mom in Texas and New Jersey, had been preoccupied with pop music since age 10, when she began visiting the D.J’s at the local Top 40 station after school. While her college dorm mates revered Bruce Springsteen, she was hanging out in a ’60s revival scene, romanticizing an era she never lived through. Eden learned about Boettcher through a friend whose father had been a D.J. The first time she heard the opening chords of “It’s You,” the first single from Begin, she got goose bumps. It wasn’t just the music, but the person the music pointed to.

At the time, Eden was going through bouts of suicidal depression, later diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder as a result of childhood sexual abuse. The music she loved suggested a joy and a sense of purity that eluded her in real life, and she decided to become a rock historian to write about the artists who, in her loneliness, she could relate to. She wrote for Mojo and Salon, interviewed Harry Nilsson and Del Shannon, but no one enchanted her like Boettcher.

When she learned of his death, she resolved to write his biography. His obscurity seemed like an injustice, and correcting it gave her a sense of purpose. When she felt suicidal, she told herself she couldn’t die because she had to write his story. Her efforts went a long way toward reviving his music: She interviewed his associates, and wrote the liner notes to several CD reissues of his work, which spread his cult in the ’90s (some of which are quoted above). In 2013 the singer Beth Sorrentino released an album of Boettcher covers, produced by Sean Slade (Radiohead, Hole).

But Eden never wrote that biography. In the end, what allayed her depression was not Boettcher, but God: In October 1999, she had a “born-again experience,” and if her name sounds familiar, it’s because she’s been very public about it. Her site, The Dawn Patrol, was well-known as a conservative blog in the early 2000s, and she was fired from a copy-editing job at the New York Post for inserting pro-life terminology into an article on in vitro fertilization (she now says she regrets this). Her first book, published in 2006, was called The Thrill of the Chaste: Finding Fulfillment While Keeping Your Clothes On.

I’ve read this book, and I’ve pored over The Dawn Patrol, sometimes with difficulty; I’ve spent years wondering what kind of person Dawn Eden might be. I was interested in Boettcher myself, and thanks to Eden’s preoccupation with him, I became interested — maybe a little preoccupied — with her.

I’m a Boettcher fan, too. I’ve loved his music ever since I persuaded an ex-boyfriend to sell me his copy of Begin. Like Eden, I was drawn to something beyond the music, though I’d have described my interest differently — where she saw purity, I saw pathos. I liked the blithe music with the tragic back story; I liked that Boettcher seemed to epitomize the kind of unsung, unjustly neglected pop genius I’ve always liked better than those who got their due. Back in university, I had some vague hopes of writing about Boettcher, though I didn’t get very far. I tracked down one or two of his colleagues and bought records he was involved with, but while I studied the names in the liner notes — Hollywood eccentrics, industry legends, footnotes of footnotes — I began to fixate on one: Dawn Eden.

The Eden I found in the liner notes was a dogged reporter, and an early adopter who had done the leg work of giving Boettcher a context. An internet search yielded another Eden, a more recent iteration: a strident conservative and chastity advocate, as well as a favorite target of Gawker. I wondered what on earth we had in common.

I found her email address easily, but sat on it for years. I worried she might shoot me down in a blaze of hellfire for even asking about her former life. When I finally got in touch, she responded right away, and seemed delighted by my interest. Boettcher’s music was still a part of her, she wrote me:

“Understand, I am not at all like those ‘born-again’ rockers who adamantly refuse to say anything at all about their pre-Christian days,” she wrote in her first response. She included a note about her new book, My Peace I Give You: Healing Sexual Wounds With the Help of the Saints, and a video of herself talking about her conversion on a Catholic TV program, in a rich, anodyne voice, like a hand petting a cat. Eden was studying for a degree in sacred theology at the Dominican House of Studies (she’s now an assistant professor of dogmatic theology), and her tone was milder than in the past. Before our first, lengthy conversation, she suggested to me that I look for the “point of continuity” between her old and new lives. It was easy to find.

A commenter on Eden’s blog once accused her of switching obsessions from rock stars to saints. She admits there’s some truth to that: each interest springs from a desire to find someone greater than she is, an example to strive toward. Many of the saints she’s written about tend toward the obscure as well — it can be difficult, she says, to develop an attachment with a saint who’s a friend to many, but an obscure saint can offer something like “your own kind of secret friendship,” in the same way that an obscure musician can offer a closeness that “I wouldn’t be able to have just with John Lennon,” she said.

This attraction to the obscure and passed over is partly altruistic, driven by the noble goal of rescuing someone’s legacy and sharing it with the world. From my secular point of view, there’s something comforting about a different kind of afterlife in the hearts of strangers, and the idea of offering that to someone long gone. But the attraction is selfish, too, because at its core — and I’m paraphrasing Eden here — is oneself. We find ourselves in the music we love, echoes of whatever we’re going through, the messages we need to hear. When we imagine the person behind the music, we incarnate a figment of our imagination — perhaps a kind of savior. The more gaps there are in an artist’s biography, the more space there is to fill.

The more you investigate, the less space there is — Eden knows this — and the harder it can become to justify one’s self-projections. Boettcher had faults like anyone — he could be a tyrant in the studio — and parts of his identity that were not faults, but might seem that way to a strict Catholic: he was not a practicing Catholic, for one, and he was gay. When I asked Eden if she’d felt conflicted about this after her conversion, she said that she probably did, but that she hadn’t wanted her views to affect the way she told his story. She could relate to Boettcher, she said, as a person looking for love; she heard a “longing for God” in his music. While she strained, sometimes, to reconcile her worldview with Boettcher’s, I strained to reconcile mine with hers. In these moments I learned more about her than him. And the more I learned the more I hypothesized, about her struggles and her motivations, because I wanted to find a bridge between us. We both worked, in our way, to find what we needed in someone else. But you can’t really know someone you don’t really know.

Curt Boettcher and Claudia Ford split up in the early ’70s, after having a child together, but remained close friends until his death. “There was something about us together that was like, I don’t know, two peas in a pod,” she said, when I reached her by phone. “We just really liked each other.” I asked her if it was gratifying to see his work find more of an audience. “Yeah,” she said, “but it’s also…” she paused. “Maddening, somehow. You know, it’s like, where were you guys? It’s frustrating for me, actually. I mean, I’m glad that it’s going on. It’s the second-best thing that could have happened, I guess.”

CURATED SERIES at HILOBROW: UNBORED CANON by Josh Glenn | CARPE PHALLUM by Patrick Cates | MS. K by Heather Kasunick | HERE BE MONSTERS by Mister Reusch | DOWNTOWNE by Bradley Peterson | #FX by Michael Lewy | PINNED PANELS by Zack Smith | TANK UP by Tony Leone | OUTBOUND TO MONTEVIDEO by Mimi Lipson | TAKING LIBERTIES by Douglas Wolk | STERANKOISMS by Douglas Wolk | MARVEL vs. MUSEUM by Douglas Wolk | NEVER BEGIN TO SING by Damon Krukowski | WTC WTF by Douglas Wolk | COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION by Chenjerai Kumanyika | THAT’S GREAT MARVEL by Douglas Wolk | LAWS OF THE UNIVERSE by Chris Spurgeon | IMAGINARY FRIENDS by Alexandra Molotkow | UNFLOWN by Jacob Covey | ADEQUATED by Franklin Bruno | QUALITY JOE by Joe Alterio | CHICKEN LIT by Lisa Jane Persky | PINAKOTHEK by Luc Sante | ALL MY STARS by Joanne McNeil | BIGFOOT ISLAND by Michael Lewy | NOT OF THIS EARTH by Michael Lewy | ANIMAL MAGNETISM by Colin Dickey | KEEPERS by Steph Burt | AMERICA OBSCURA by Andrew Hultkrans | HEATHCLIFF, FOR WHY? by Brandi Brown | DAILY DRUMPF by Rick Pinchera | BEDROOM AIRPORT by “Parson Edwards” | INTO THE VOID by Charlie Jane Anders | WE REABSORB & ENLIVEN by Matthew Battles | BRAINIAC by Joshua Glenn | COMICALLY VINTAGE by Comically Vintage | BLDGBLOG by Geoff Manaugh | WINDS OF MAGIC by James Parker | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA by Lynn Peril | ROBOTS + MONSTERS by Joe Alterio | MONSTOBER by Rick Pinchera | POP WITH A SHOTGUN by Devin McKinney | FEEDBACK by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FTW by John Hilgart | ANNOTATED GIF by Kerry Callen | FANCHILD by Adam McGovern | BOOKFUTURISM by James Bridle | NOMADBROW by Erik Davis | SCREEN TIME by Jacob Mikanowski | FALSE MACHINE by Patrick Stuart | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 MORE DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE (AGAIN) | ANOTHER 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | UNBORED MANIFESTO by Joshua Glenn and Elizabeth Foy Larsen | H IS FOR HOBO by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FRIDAY by guest curators