On Beyond Zarathustra: Notes

By:

October 10, 2016

On Beyond Zarathustra: A Double-Parody For All And None

“Don’t you believe in Zoroaster? Is it possible that you neglect Mumbo-Jumbo?” — G. K. Chesterton, The Napoleon of Notting Hill

I.

On Beyond Zarathustra [serialized, in part, here at HILOBROW] ought to need no introduction — if I’ve done my job. This is parody of philosophy. The formula is simple: philosophy is nonsense, naïve and childish… so rewrite it as a children’s nonsense book. I added the second step, but the first is old, albeit tendentious.

Let me quote Plato first, then Nietzsche:

“It is a fine thing to partake of philosophy just for the sake of education, and it is no disgrace for a lad to follow it: but when a man already advancing in years continues in its pursuit, the affair, Socrates, becomes ridiculous; and for my part I have much the same feeling towards students of philosophy as towards those who lisp or play tricks. For when I see a little child, to whom it is still natural to talk in that way, lisping or playing some trick, I enjoy it, and it strikes me as pretty and ingenuous and suitable to the infant’s age; whereas if I hear a small child talk distinctly, I find it a disagreeable thing, and it offends my ears and seems to me more befitting a slave. But when one hears a grown man lisp, or sees him play tricks, it strikes one as something ridiculous and unmanly, that deserves a whipping. Just the same, then, is my feeling towards the followers of philosophy. For when I see philosophy in a young lad I approve of it; I consider it suitable, and I regard him as a person of liberal mind: whereas one who does not follow it I account illiberal and never likely to expect of himself any fine or generous action.”

That’s cynical Callicles, the Grinch of the Gorgias — whose head is full of wonderful, awful ideas.

Now Nietzsche:

“What stimulates one to look at all philosophers in part suspiciously and in part mockingly is not that we find again and again how innocent they are — how often and how easily they make mistakes and get lost, in short, how childish and child-like they are — but that they are not honest enough in what they do, while, as a group, they make a huge, virtuous noise as soon as the problem of truthfulness is touched on, even remotely.”

Neither passage suggests the natural, next Seussian step, but it’s not much further on beyond Beyond Good and Evil.

Callicles implies he might like philosophy fine if only it were spoken by or to a child, in a manner appropriate to children. (And that’s why I’m eventually going to give you If I Ran The Polis and Socrates, Will You Please Go Now! Maybe it would be fun to rewrite Spinoza’s Ethics as a series of lisping tongue-twisters.)

Nietzsche implies that childishness with a bug in its ear about Truth is especially stimulating, so a formula suggests itself: a classically Seussian, compulsively fabulist, infantile protagonist, compulsed to fabulate with self-righteous indignance on behalf of… Truth!

II.

Speaking of Seuss’ boys, here is a list. (I think it’s complete, but I might have missed one.)

Note how none of these characters does anything. They just dream … Everything! (Oh, the Thinks you can Think! No companion volume entitled All the Do’s You Can Do. Could any failure to deliver be more pregnant with philosophy’s weakness, in the midwifery department?)

Marco, from And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street, McElligot’s Pool and “Marco Comes Late” (available in Horton and the Kwuggerbug and More Lost Stories.)

Morris McGurk, from If I Ran The Circus.

Gerald McGrew, from If I Ran The Zoo.

Peter T. Hooper, from Scrambled Eggs Super!

The unnamed protagonist from On Beyond Zebra.

Henry McBride, from “The Great Henry McBride” (in The Bippolo Seed and Other Lost Stories.)

We add, for good measure, the sister/brother tag-team from “The Glunk That Got Thunk” (from I Can Lick Thirty Tigers Today!)

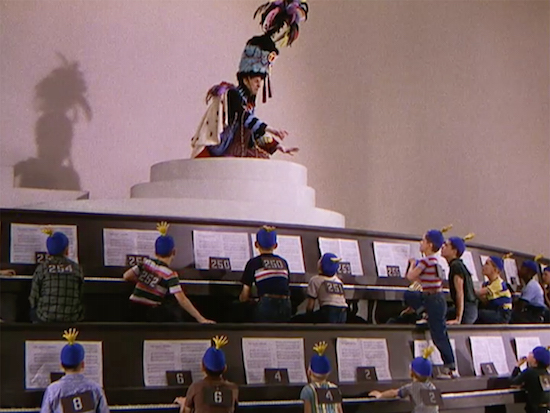

Bartholomew Collins, from the Seuss film, The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. Young Bart ends up setting off a bomb of his own imaginative invention to blow up what is basically a concentration camp for boys.

“Is it… atomic?” “VERY atomic, sir!”

Serious stuff! Of course, it was all just a dream… or IS it?

III.

Which flips us from good over to evil… and beyond? The psychological profile of a Seussian adult villain is not different from that of a good, Seussian boy. They are megalomaniacs with Rube Goldbergian tendencies.

Dr. Terwilliker’s mad vision of 500 boys playing a giant, biomorphically curved piano keyboard in unison; the Once-ler’s indominable, entrepreneurial dream of needlessly selling everyone a thneed; King Derwent’s perverse determination to blanket his kingdom in Oobleck; the king turtle with the fetish for turtle-stacking, subsequently dethroned by Yertle; the Grinch, whose strategy is preposterously indirect, and who — like any good boy — has the superpower of thinking up a lie, and thinking it up quick; foolish Gertrude McFuzz (not a villain, but, then again, King Derwent isn’t villainous, just misguided. Same with the Once-ler.)

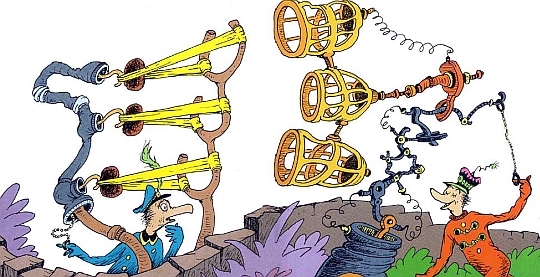

Most ghastly: the Backroom Boys, in The Butter Battle Book, escalating violence up the ladder of imagination, from mere Triple-Sling Jiggers to world-busting Bitsy Big-Boy Boomeroos. But here again, one suspects if they only got out of their Backroom — got outside their own heads — they would see the error of their ways.

It’s tempting to say Seuss is just a good liberal. (Callicles and Lionel Trilling might agree, albeit in different keys!) Imagination is fine and even necessary… in its place. Public and private spheres are separate. Think King Birtram in The King’s Stilts: “When he worked, he really worked… but when he played, he really PLAYED.” If people can’t do silly, harmless things in private, nothing great and helpful will ever get done in public.

Thus, the formula for another class of Seuss villain: Lord Droon, who hides the king’s beloved stilts; the kangaroos, who seem offended by the very notion that Horton might have found something heretofore unimagined. The younger protagonist in On Beyond Zebra, initially content to stop at Z, is another instance. Not a villain, but initially not on the true path.

Does “The Glunk That Got Thunk” imply that girls should use their imaginations less than boys? Let’s piously hope not. That would be untrue to true Seussianism.

Life isn’t worth living, or won’t be lived to the fullest, without grand schemes between our ears. But it would be wrong to force those schemes on non-consenting others, out in the real world.

It’s innocently charming that Morris McGurk keeps assuming “Sneelock won’t mind,” because we know the child lacks the power to compel an adult to do any of these mad, dangerous things. But these zoo-and-circus dreams would turn sinister — imperial, colonial, totalitarian — if they were, per impossibile, put into practice. (See also: Plato’s Republic.)

Not that it’s easy to separate public and private, to draw that line clean. One can’t help what sprouts from one’s head, after all, and often all that gets loose in the public sphere. We hope it works out. See: The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins and (this one completed posthumously) Daisy-Head Maysie.

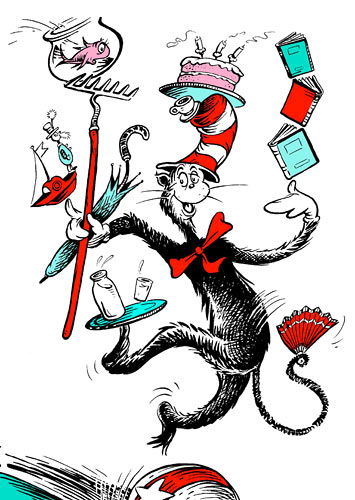

The Cat In The Hat, the single greatest Seussian creature creation, generates creative-destructive mess in other people’s rightly private spaces, like a villain, yet has the power to reset everything back to normal, as if it had been only a dream in the head of a child. In The Cat In The Hat Comes Back, he sets off a reverse-bomb: Voom boom, inducing order out of chaos.

The Cat lets us have our imaginative cake — on a rake! with a fish and a dish — and eat it, too.

Should we live like the Cat? Let our imaginations overrun, slopping over into other peoples’ spaces? — in the confidence that somehow it will all tidy itself away in the end? Or is that a recipe for thoughtlessly cutting down the last truffula tree to knit a thneed no one needs?

IV.

And what about Beyond? What of Nietzsche’s Overman? Bart Collins sings, sadly, in 5,000 Fingers:

Now just because we’re kids

Because we’re sort of small

Because we’re closer to the ground

And you are bigger pound by pound

You have no right

You have no right

To push and shove us little kids around.Now just because your throat

has got a deeper voice

And lots of wind to blow it out

At little kids who don’t dare shout

You have no right

You have no right

To boss and beat us little kids about.Just because you’ve

Whiskers on your face to shave

You treat us like a slave

So what? It’s only hair.

Just because you wear

A wallet near your heart

You think you’re twice as smart

You know that isn’t fair.But we’ll grow up some day

And when we do I pray

We won’t just grow in size and sound

And just be bigger pound by pound

I’d hate to grow

Like some I know

Who push and shove us little kids around.

That doesn’t sound like he is awaiting the Overman.

On the other hand, Bart promptly builds an atomic bomb.

V.

Children should let their imaginations run wild. There’s no harm in it, and a great deal of good.

But Dr. Seuss didn’t write books about, or for, children.

From Dr. Seuss and Mr. Geisel, by Judith and Neil Morgan:

Much of the time he didn’t think of himself as a children’s book author. Ted simply did what he did; he drew and wrote rhymes. He honed his drawing style with his first books, and half a century later it was essentially unchanged. He had researched children’s literature in a brief spurt in 1949, but it was no longer on his mind. He was glad that millions of children and their parents liked his books, but he wrote and drew above all to amuse himself. (213)

From Dr. Seuss: American Icon, by Philip Nel:

Perhaps a desire to surprise people inspired Seuss’s mischievous — and definitely adult — sense of humor. Although Seuss was fond of saying, “Adults are obsolete children, and the hell with them,” he also admitted, “The first draft of all my stuff is written completely for adults. To keep the story going, to keep in the swing, I’ll write swear words and dirty words and everything else — ending up with an adult piece of writing that a child could comprehend. Then I go back and clean up, have a little fun with it (Pace D23; Danguard 5). To make sure that his editors were paying attention, he liked to slip dirty jokes into his manuscripts. In the documentary, An Awfully Big Adventure: The Making of Modern Children’s Literature (BBC, 1998), Michael Frith shows a darft page from Dr. Seuss’s ABC, in which Seuss has drawn a large-breasted woman and the following verse: “Big X, little x. X, X, X/ Someday, kiddies, you will learn about SEX.” (101)

Nel quotes from a panel discussion involving Seuss and Maurice Sendak. The authors were asked to say how their childhoods influenced their work. Seuss — who watched parades down an actual Mulberry Street, growing up; whose father actually ran the zoo (yes he did!) — replied:

“Not to a very great extent. I think my aberrations started when I got out of my early childhood… Generally speaking, I don’t think my childhood influenced my work. But I know Maurice’s did.”

Sendak agreed: “I have profited mightily from my early childhood,” he said.

Seuss: “I think I skipped my childhood.”

Sendak: “I skipped my adolescence. Total amnesia.”

Seuss: “Well, I used my adolescence.” (98)

Male adolescence is the age for sex-and-power fantasies, when the imagination runs wild.

Of course, it would be wrong to say, therefore, that the Seuss books we’ve got are actually about all that. Consider Louis Menand, “Cat People”, from The New Yorker (December 23, 2002):

Every reader of “The Cat in the Hat” will feel that the story revolves around a piece of withheld information: what private demons or desires compelled this mother to leave two young children at home all day, with the front door unlocked, under the supervision of a fish? Terrible as the cat is, the woman is lucky that her children do not fall prey to some more insidious intruder. The mother’s abandonment is the psychic wound for which the antics of the cat make so useless a palliative. The children hate the cat. They take no joy in his stupid pet tricks, and they resent his attempt to distract them from what they really want to be doing, which is staring out the window for a sign of their mother’s return. Next to that consummation, a cake on a rake is a pretty feeble entertainment.

This is the fish’s continually iterated point, and the fish is not wrong. The cat’s pursuit of its peculiar idea of fun only cranks up the children’s anxiety. It raises our anxiety level as well, since it keeps us from doing what we really want to be doing, which is accompanying the mother on her murderous or erotic errand. Possibly the mother has engaged the cat herself, in order to throw the burden of suspicion onto the children. “What did you do?” she asks them when she returns home, knowing that the children cannot put the same question to her without disclosing their own violation of domestic taboos. They are each other’s alibi. When you cheat, you lie.

That’s plain nuts. Nonsense! Honestly, it’s a more innocent book. But, genealogically, there’s probably truth to it. That’s why I decided to write On Beyond Zarathustra. There ought to be Seuss books of which the sorts of obviously false claims Menand makes would be true.

Just as there ought to be an eternally-unfinished Seuss museum such as Seuss envisioned, but couldn’t so much as begin.

“Purposes,” Seuss writes, “To help a child’s imagination get off the ground before it’s pinned down to the ground forever.” In order to inspire children to keep thinking, Seuss conceived of the museum as never being finished, but always being in flux so that children could perpetually be involved in creating it. As he put it, “I would keep the museum forever in a n uncompleted state… not a state of confusion, but a state of challenge. Putting the fresh (but usually impractical) excitement of youth against the mature (but usually stuffy and stodgy) wisdom of us elders.” For example, he envisioned an “ever-changing pathway” between two wings of the museum. One year, children would work “under the supervision of a Mexican brick maestro” to make a brick pathway. Three years later, perhaps they would remake the walkway as a glass-and-tile mosaic. Later still, the children might “dig it up and replace it with a red wood boardwalk.” In this way, he hoped to provoke children to think, to be creative, and to challenge the grown-ups. As he put it, “I want to see a bunch of scrappy kids talking back to us. And I want to sit back among the elders and tell that kid, ‘O.K., Bud, I think, according to my experience, you’re wrong. But if you’re so sure of yourself that you think the back steps should be painted magenta — get your gang together and paint them magenta. We’ll buy you the paint.” (Nel, 93)

The closest he got was: “grade-school kids excitedly picked through piles of Barbie-doll heads, eyeballs, limb, and torsos for parts to build an abstract model of a city.” (quoted by Nel, p. 94, from a 1967 Newsweek article about “The Logical Insanity of Dr. Seuss”)

VI.

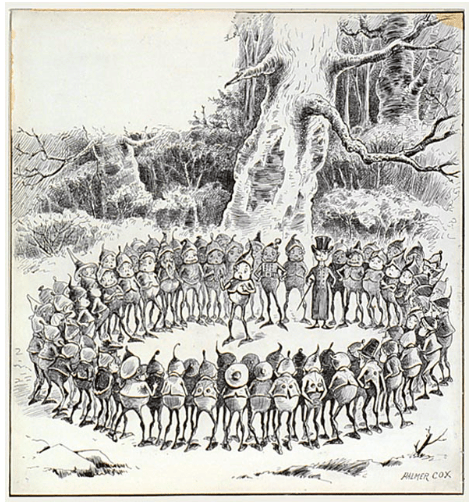

Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra has often been accused of being adolescent, in an ungainly, unsavory way. So that’s why I draw him that way, by the way. Also, I’m nodding to one of Seuss’ childhood artistic influences: Palmer Cox’s Brownies.

I don’t think that’s a correct reading of Nietzsche; or rather, it mistakes a deliberate literary feature for a bug. Nietzsche knows Zarathustra looks like a wise-fool. He is aware there is as much Holden Caulfield as Siegfried in his faux-Persian protagonist. Although Nietzsche never heard of Holden. But he’d read bad German Romantic stuff. How could he not know?

Also, Nietzsche was painfully aware of the World As Will and Rube Goldberg device:

The artist is related to the lovers of his art as a heavy cannon is to a flock of sparrows. It is an act of simplicity to start an avalanche so as to sweep away a little snow, to strike a man dead so as to kill a fly on his nose. The artist and the philosopher are evidence against the purposiveness of nature as regards the means it employs, though they are also first-rate evidence as to the wisdom of its purpose. They strike home at only a few, while they ought to strike home at everybody – and even these few are not struck with the force with which philosopher and artist launch their shot. It is sad to have to arrive at an assessment of art as cause so different from our assessment of art as effect: how tremendous it is as cause, how paralysed and hollow as effect! The artist creates his work according to the will of nature for the good of other men: that is indisputable; nonetheless he knows that none of these other men will ever love and understand his work as he loves and understands it. (“Schopenhauer As Educator”, section 7, trans. R. J. Hollingdale.)

Of course, this disconnect from reality only serves to exemplify the deep harmony between philosophers, artists and Nature. What if She ran the Zoo?

Nature seems to be bent on squandering; but it is squandering, not through a wanton luxuriousness, but through inexperience; it can be assumed that if nature were human it would never cease to be annoyed at itself and its ineptitude.

And now you know why I let Zarathustra rattle on like that, to the townsfolk.

At any rate, I think that, just as Seuss books are children’s books for adults, so Zarathustra — and other philosophy I might mention — is seeming YA fiction, secretly written as non-fiction for older adults. Who are, in a sense, true children at heart.

Is it the secret pride of childhood that it is already more adult than we suspect? Or the secret pride of adulthood that we remain children at heart? It doesn’t seem like both stages could be above the other (even if an ouroboros of sufficient knottiness might make it appear so.)

True story: my mother says that she asked me, age 5, why I was so silly. I thought about the problem, seriously, and replied: “I was borned by Dr. Seuss.” I’m pushing 50. It took me a while to get around to full delivery.

HOLBO AT HILOBROW: On Beyond Zarathustra — a double parody | Sugarplum Squeampunk — Christmas cards by deranged Victorian “cthuligrapher” Albert Wedge-Wheskit | Not Trash, Pop — a celebration of forgotten midcentury gag panel artist Susi Steinitz Ettinger | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: The Conan Mythos | HERMENAUTIC TAROT: The Heaviest Heads.

MORE NIETZSCHE & SEUSS: Josh Glenn’s ZARATHUSTRA VS. SWAMP THING mashup | THE ARGONAUT FOLLY pt. 2 | Nietzsche as HILO HERO | Dr. Seuss as HILO HERO | Greg Rowland and Joe Alterio’s MY FIRST CRITICAL THEORY ABC.