Rebooting Museums (4)

By:

June 18, 2011

Within the BSG miniseries “Razor,” Admiral Adama asks Commander Apollo Adama to search for a missing Raptor; the ship embarked on a journey to study a supernova remnant, and the crew’s return is long overdue. Pursuing the missing Raptor’s course, Apollo and the Battleship Pegasus unexpectedly engage in a firefight with Cylon war ships. The battle causes a critically damaged Cylon Raider to unintentionally land on the Pegasus flight deck. “I’ve never seen one of these outside of a Museum,” Colonel Tigh muses, upon viewing the fighter plane; this unexpected acquisition appears to be outside of its own time — the machine’s design and (defunct) occupants echo those from the 1978 version of the series and BSG’s historical, first Cylon War.

Fourth in a series of posts using the rebooted Battlestar Galactica franchise as a lens through which to view museums’ challenge to reinvent themselves. (Series intro here.)

This anachronistic vessel, and the base ship it’s protecting, appear in a completely unexpected sector of space; the Pegasus’s discovery of its existence instigates multiple opportunities — we learn something about the earlier Cylons (seen in the 1978 series and glimpsed as relevant artifacts in the Museum views of BSG’s initial miniseries), Admiral Adama’s last encounter with the Cylons at the end of the first war, and something about how the Cylons evolved from the past to their present forms. This ship’s serendipitous discovery leads to an additional universe of information. In this post, I’ll concentrate on potential ways that unexpected discovery could inspire designers to seek out opportunities for connection and investigation.

Docent- or map-guided tours have been a staple of general museums’ programming. Current development of applications for personal mobile devices has enabled cultural organizations to extend this type of experience to allow visitors to instigate explorations on their own devices and within their own timeframes. A mobile app facilitates self-guided tours of The Vatican, for example, or you could experience the “film” Murder On Beacon Hill in the Boston neighborhood from which it takes its name. Follow the paths, using these and many other applications, and you’ll experience a powerful but relatively traditional multimedia tour inside or outside of cultural institutions’ walls.

Partially guided solutions for exploration also exist. If you leave the app open on your iPhone or iPad, the Museum of the Phantom City — an app that shows unbuilt, visionary architectural projects — glows when you near an appropriate locale. The Broadcastr app includes a function called “Geoplay”; when activated, you automatically receive the most proximate piece of audio. Walk around with headphones on and the app open, and you could experience — depending on your current location — stories ranging from the personal accounts of Holocaust concentration camp survivors to a playful experience created by the Neo-Futurists up the length of 2nd avenue in New York.

Many examples exist for the two paradigms I mention above. What I would like to concentrate on, however, are the possibilities for true stumble-upon experiences. In this post, I adopt (Director of Technology for the Denver Art Museum) Koven Smith’s use of the word serendipity as an exemplar for thinking about ways to “pursue an entirely different kind of interaction model, one that substitutes… for the more immersive, intentional ones that museums are accustomed to.” Nancy Proctor, the Head of Mobile Strategy & Initiatives for the Smithsonian, often speaks about the opportunity to imagine “un-tours.” Thinking along the lines of the BSG example — the possibilities for an unexpected encounter to instigate paths for further information, connection, and desire for discovery — I’ll reference four existing non-museum projects that may spark some ideas.

In the summer of 2010, the Christina Ray Gallery encouraged people to wander the city, keeping an eye out for unexpected things. As a part of an in-gallery exhibition called “Mission: Edition,” Ray – the founder of the NYC-based psychogeography festival, Conflux — instigated a scavenger hunt for associated prints left in tubes at various locations in New York. Concerted participants followed the Gallery on Twitter and Foursquare, receiving clues as new prints appeared. However, because of the public locations, unknowing participants could stumble upon these art gifts as well. As Jennifer Gickel wrote in DNAInfo:

The prints will be left rolled up in tubes at various kinds of spots, such as bars, parks, or libraries. Because of the inherently public nature of such locations, Ray acknowledged that passersby could snag the artwork before those participating in the scavenger hunt would have the opportunity to figure out and reach the hiding spot.

I spoke with Ray, not long ago, while writing writing an article on design for personal mobile devices for Curator: The Museum Journal, and she shared with me her insight that New Yorkers (and people in general) fall into two categories: those who peek through the plywood of construction sites and those who don’t. Ray’s “Mission: Edition” celebrates the first type. Ray also explained that any found tube included a short description of “Mission: Edition” along with the art, so that any accidental finder would know what she’d found. This description might inspire an accidental participant to find her way back to the Gallery, to begin to play the game to find additional art in coming days, or to simply look more closely within the city (i.e., for other treasures that might be found).

Whereas “Mission: Edition” gave people the ability to either intentionally participate or accidentally stumble-upon the objects, “Soundawards,” a project by the London-based art collective greyworld, appears to be a stumble-upon and/or contribute paradigm. Initiated in 1998, “Soundawards” began “as an ongoing art scheme in urban areas. Originally, the awards were installed without permission, appearing overnight in areas of outstanding sonic importance.” Concentrated in urban spaces, the project focused on “the unmarked Sonic Monuments that exist in cities.” According to greyworld, “In many ways, these are truer works of public art than the bronze statue or the highly polished rock we often find in cities. Secondly, whilst greyworld created the system, anyone [could] award a location a Soundaward and log its location.” Though the greyworld website states that the collective maps of current “Soundawards” locales will appear online, the current “Soundawards” site holds a static page; these “awards,” now “installed permanently,” exist — at this moment — exclusively for a serendipitous experience. The discovery of a Soundaward could inspire an unintentional sound explorer to respond through one or more ways: pause and concertedly listen to the sounds of that space, explore a myriad of stories through the aid of a future online map, and/or possibly contribute her own nominee (should the website allow for contributions to resume).

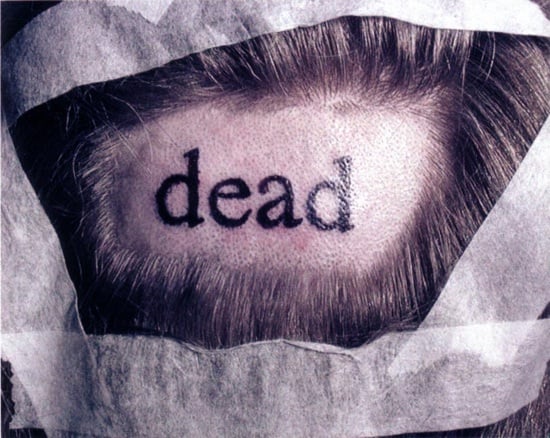

Explorable landscapes can include more than physical space. One of my favorite distributed storytelling projects, Shelley Jackson’s “Skin,” began in 2003 with a call for participants in Cabinet Magazine. Jackson distributes the words of a short story (an ongoing project, 1445 words have been mailed as of 2010) through tattoos created upon the bodies of 2095 individuals. The “words” (as the volunteers are called) sign non-disclosure agreements; only they and Jackson know the totality of the text. We — as outsiders — can only stumble-upon the story one participant at a time. In Daniel Pink’s 2004 New York Times article, “The 4th Annual: Year In Ideas; Skin Literature,” he wrote of the potentially connective experience for the participants themselves:

Jackson is encouraging her far-flung words to get to know each other via e-mail, telephone, even in person. (Imagine the possibilities. A sentence getting together for dinner. A paragraph having a party.)

Creating further iterations, Jackson has recently recombined the words into new manifestations. In March 2011, she created “Skin 2.0” for an exhibit at the Berkeley Art Museum. Jackson asked her “words” to upload videos of themselves speaking their word aloud; she then edited the spoken words into new pieces of video-recorded prose.

The serendipity of encountering a “Skin” participant could open up doors to explore the story of the past instigation, present manifestations, and any possibilities for the future that Jackson may devise. As Carolyn Kellogg writes in her LA Times article on the project:

“Skin is ceaselessly remixing itself as its words wander around the world, and in a sense my original story is only one of countless stories that it tells,” Jackson wrote to Jacket Copy. She added, “The video I’ve put together is one way of gesturing toward that, but it would also be interesting to open up a space for other people to assemble their own stories out of the same material.”

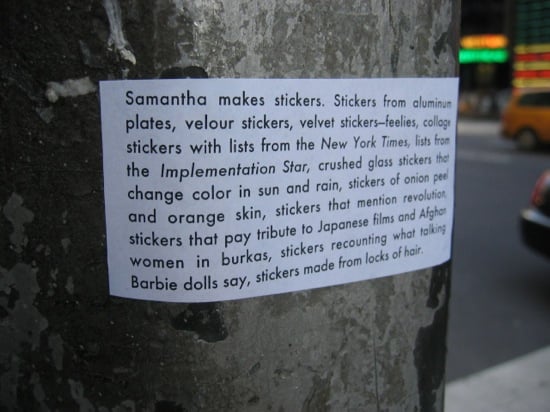

I’ll end this post with just one more example, a project that I will return to in more detail later within this series. “Implementation,” begun in 2004 by Nick Montfort and Scott Rettberg, “borrows from the traditions of net.art, mail art, sticker art, conceptual art, situationist theater, serial fiction, and guerrilla viral marketing.” At its simplest, it’s a sticker novel placed in public space. Originally created as eight installments, Montfort and Rettberg distributed packages of printed mailing labels to willing participants, who then placed (and photographed) individual stickers throughout their own public spaces. As Montfort and Rettberg write, “We hope that this form of interaction will engender new and unanticipated meanings as Implementation is situated in specific public spaces that resonate with the texts in different ways.”

The original project photographs appear on the “Implementation” project site; the locations range from Absecon, New Jersey to Volda, Norway, and the dates range from early 2004 to mid-2006. In preparation for a book (currently in process), Rettberg created a second collection on Flickr. He applied stickers to the streets of Bergen, Norway, in early 2010, and his Flickr collection includes images posted as late as November 2010. The viewing of these images enables one means of reading the text.

The novel itself can be read in part or whole. The layouts for the original installments are downloadable from the project site to read or reprint. The text itself is written in such a way that an individual sticker operates as a tiny portal into the “Implementation” world; I’ve read the entire text, and it’s a solid novel as a whole — however, it is written in a way in which both glimpses and thorough readings include something to behold. Part of the wonder of the methodology of “Implementation,” for me, is not only the multiple points of entry and numerous possibilities to stumble into this story universe, but also its ability to resituate the understandings of the story and its spatial homes in an infinite variety of ways through a very simple physical form.

If we return to the BSG example that I noted earlier, we’re reminded that the serendipitous encounter with a single object can open up a universe of possibilities for exploration of further information, connection, and want for discovery. “Where the hell did they come from?” Commander Apollo Adama asks upon first seeing the anachronistic Raider, and its outdated Cylon crew, on his flight deck. What’s more important than origin, both in BSG and the project examples I mention, is where we can go next.

READ other HiLobrow series: ANGUSONICS — the solos of Angus Young | ARTIST IN RESIDENCE — HILOBROW’s favorite artists | BICYCLE KICK | THE BOOK IS A WEAPON — a gallery | CABLEGATE COMIX | CECI EST UNE PIPE — a gallery | CHESS MATCH — a gallery | DE CONDIMENTIS — a world-secret-historical take on ketchup, mustard, relish, and more | DIPLOMACY — a world-conquest boardgame musical | DOTS AND DASHES — a gallery | DOUBLE EXPOSURE — the stratagems of Middlebrow | EGGHEAD — a gallery | EPIC WINS — our versions of epic poems | FILE X — a gallery | FITTING SHOES — famous literary footwear | GOUDOU GOUDOU — adventures in Haiti | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM — 25 Jack Kirby panels | LATF HIPSTER | MERIT BADGES — earn ’em! | MOULDIANA — the solos of Bob Mould | PANTENE MEME — a found gallery | PHRENOLOGY — the insane origin of browism | PLUPERFECT PDA — time-traveling smartphones! | POP ARCANA — spelunking weird culture | REBOOTING MUSEUMS | ROPE-A-DOPE — boxing | SECRET PANEL —Silver Age comics’ double entendres | SHOCKING BLOCKING — cinematic blocking | SKRULLICISM | UKULELE HEROES