Rebooting Museums (3)

By:

June 3, 2011

“It’s no secret: American children are behind in math and science, and falling faster by the year,” writes Maywa Montenegro in an April 2011 SEED article titled “The Art of Science Learning.” “[R]estoring ‘STEM’ [science, technology, engineering, and mathematics-related learning] in America must go beyond multiplication drills, beyond the latest in computer apps.”

Third in a series of posts using the rebooted Battlestar Galactica franchise as a lens through which to view museums’ challenge to reinvent themselves. (Series intro here.)

In recent years, science centers and museums have utilized the presence of blockbuster exhibitions on popular culture topics to bring in larger, potentially more diverse audiences. One of the biggest examples has been Harry Potter: The Exhibition.

At first glance, the Potter universe might be a natural fit for STEM-learning venues; J.K. Rowling’s novels have been used as a launching point for a variety of scientific discussions. For example, the National Library of Medicine put together a display that contextualizes selected Potter themes with renaissance scientific thought. In a 2005 article, USA Today featured a Norwalk, Va., teacher who planned to use the Potter books as a starting point to teach remedial science to her eighth graders. And books such as The Science of Harry Potter (written by the science editor of the London Daily Telegraph) exist.

However, there have been questions about the appropriateness of not only popular culture, but this particular exhibit, within a museum/center scientific learning context. In response, in his August 2009 article “Does Harry Potter Belong at Boston Museum of Science?” Scott Kirsner quotes the BMS’s vice president of education as saying, “The museum ‘takes its mission seriously, and we think you can take pop culture and make it relevant to science and technology and engineering.’” I would agree with the statement, but I agree with the questioning of this exhibit; my viewing of the same exhibition was one void of STEM-related content.

Imagining our own relevancy, a scientifically well-versed colleague and I created our own narrative while exploring the exhibit at another science-related location. In addition to the connections of alchemy, plant biology, and other assorted Hogwarts topics, there are significant STEM underpinnings behind the filmmaking, set design, costuming, and visual effects shown in the exhibition. In his post “Harry Potter: The Exhibition, or what Location Entertainment Adds to a Transmedia Franchise,” Henry Jenkins explains that the audio tour — an option that my colleague and I did not choose — gives visitors a behind-the-scenes narrative about the choices behind the artifacts’ design. However, Jenkins states that the technical descriptions pulled him out of the fictional world that the exhibit otherwise presents, breaking rather than reinforcing the synergy between the science and magic involved.

In her above-referenced article, Montenegro reports on a meeting convened with intellectual innovators to rethink America’s approach to science education. “Instead of thinking purely in terms of technological innovations,” Montenegro writes, “these experts believe that infusing some art and design into math and science learning can restore curiosity, energy — and ultimately, performance — to STEM in America.” If the base exhibit is void of STEM content, and its tacked on inclusion breaks rather than adheres to the magic of the topic, are we taking best advantage of popular culture’s ability to spark interest in new topics? Could the exhibition have been designed in a way more inherently connected to its science-related homes?

Returning to the topic of Battlestar Galactica, the pop culture reference for this series’ previous installments, might show us another approach. According to a book called The Science of Battlestar Galactica by Patrick Di Justo and Kevin R. Grazier, scientific study was central to the development of BSG. Grazier is noted as the “scientific advisor” to the series, and, in her introduction to the text, co-executive producer Jane Espenson writes, “The point of Battlestar Galactica was not, ultimately, science. It was a show about the human condition, hope, and moral grayness. But science didn’t distract us from telling the stories we wanted to tell. It helped us. And Kevin helped us get the science right.”

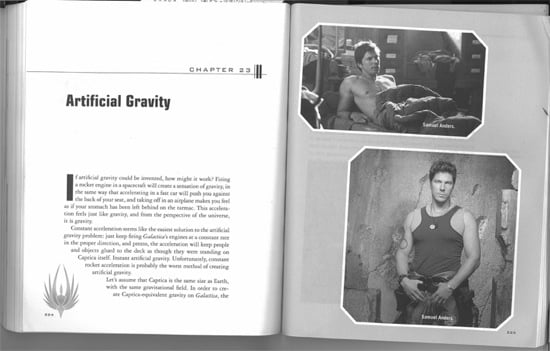

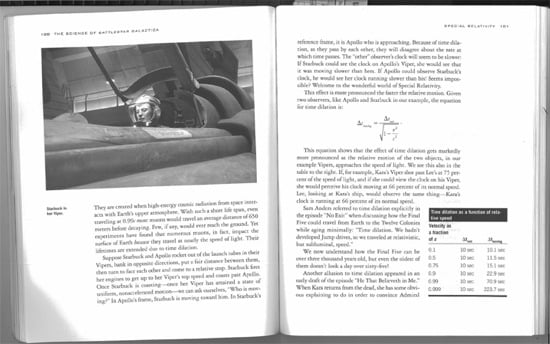

As someone versed more in the culture of science than science fiction, The Science of Battlestar Galactica makes me laugh quietly with twisted admiration. The book allows me to view beefcake photos of the character Samuel Anders as I launch into the chapter on “Artificial Gravity,” and a rare image of Kara “Starbuck” Thrace in a dress peers at me across from a page that starts “Nine years later, when the Mongols were invading Europe…” This is a book made for fans — still, it doesn’t dumb science down.

This book treats the series’ fans as intelligent human beings by opening minds to the scientific facts considered behind the choices made on screen. For example, the episode titled “33” is an interesting mélange of BSG themes — from science to serendipity, rationality to religion; the science behind this episode ranges from biology to battleships. In this first episode after the miniseries that re-launched Battlestar Galactica as BSG, the fleet is on the run. Cylons inexplicably appear every 33 minutes. The pilots have not slept in days. The fleet fights off cylon after cylon and makes “jump” after “jump” until a choice is made (late in the episode) that appears to cease the onslaught and help the fleet survive to fight another day.

As Dr. Gaius Balthar says, anticipating yet another jump while aboard the Colonial One, “Five days now. There are limits to the human body, the human mind, tolerances that you can’t push beyond. Those are facts, proven facts. Everyone has a limit.” The characters show immense physical and mental frailty, and the Galactica pilots are ordered to take “stims,” one of the many drugs included in the Science chapter titled “The Colonial Pharmacopeia.” In a parallel plotline back on Caprica, we see the character Helo struggling to survive; between escaping cylons, he routinely shoots himself with medication marked “Anti-Radiation.” The authors of Science use the presence of this medication as an opportunity to explain a very specific fact about the biological effects of nuclear war. According to the “Pharmacopeia” chapter:

One dangerous component of nuclear fallout is the isotope iodine-131. Just like regular iodine, iodine-131 concentrates in the thyroid, which is bad because you really don’t want radioactive material to concentrate anywhere. Helo is almost certainly injecting saturated concentrations of potassium iodide into his neck, thereby concentrating “good” iodine in his thyroid. If he subsequently eats or breathes in any radioactive iodine, it will find that there’s no more room in his thyroid, and will be excreted from his body.

The humans of BSG need to push themselves, and the functions of the ships appear strained. Discussions between characters remind us that a new jump every 33 minutes can create immense stress on the resources and infrastructures of the carriers themselves. The jump mechanisms are referred to as FTL (Faster-Than-Light) drives. Described as a classic science-fiction trope, the authors of Science acknowledge that this particular detail is one in which “[Ronald D.] Moore’s Law” (described in the Introduction as “We always tried to make drama work with science on BSG, but when push comes to shove, drama wins”) may apply. However, they use the FTL-imaginative leap as an opportunity for further scientific discussion:

[W]e are looking at flinging a quantity of mass on the order of 120 teragrams (120 billion kilograms, or about 132 million tons) across the cosmos. Is that even remotely possible, to send something approaching the mass of a thousand Nimitz class aircraft carriers several light-years away? Or is this where the First Law of BSG comes into play? Obviously, no human alive knows exactly how an FTL drive works. Nevertheless, we can ponder some of the relevant physics that may one day lead us to FTL travel, and will yield a drama-driven plot element based upon known physics.

The chapter then proceeds to talk about theories of teleportation, hyperspace, wormholes, space warps, and caffeine. And the book as a whole covers topics from “What is the Mass of Battlestar Galactica” to “Cylon Intelligence and the Society of Mind.”

The series itself is science fiction, but The Science of Battlestar Galactica opens up worlds of possibilities for imaginative leaps into relevant STEM topics. I reference the Harry Potter exhibit to show that we are not necessarily exploiting the powerful opportunities that fun pop culture references hold; the playful richness of the BSG example makes me ask, why not?

READ other HiLobrow series: ANGUSONICS — the solos of Angus Young | ARTIST IN RESIDENCE — HILOBROW’s favorite artists | BICYCLE KICK | THE BOOK IS A WEAPON — a gallery | CABLEGATE COMIX | CECI EST UNE PIPE — a gallery | CHESS MATCH — a gallery | DE CONDIMENTIS — a world-secret-historical take on ketchup, mustard, relish, and more | DIPLOMACY — a world-conquest boardgame musical | DOTS AND DASHES — a gallery | DOUBLE EXPOSURE — the stratagems of Middlebrow | EGGHEAD — a gallery | EPIC WINS — our versions of epic poems | FILE X — a gallery | FITTING SHOES — famous literary footwear | GOUDOU GOUDOU — adventures in Haiti | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM — 25 Jack Kirby panels | LATF HIPSTER | MERIT BADGES — earn ’em! | MOULDIANA — the solos of Bob Mould | PANTENE MEME — a found gallery | PHRENOLOGY — the insane origin of browism | PLUPERFECT PDA — time-traveling smartphones! | POP ARCANA — spelunking weird culture | REBOOTING MUSEUMS | ROPE-A-DOPE — boxing | SECRET PANEL —Silver Age comics’ double entendres | SHOCKING BLOCKING — cinematic blocking | SKRULLICISM | UKULELE HEROES