Hilobrow Podcast: ROBOTS

By:

January 30, 2010

Here it is: the first episode of “Parallel Universe: Pazzo,” HiLobrow.com’s Radium Age Science Fiction podcast, recorded every month (as of January ’10) at Pazzo Books, here in Boston. Below, you’ll find an introduction to Radium Age (roughly, 1900-35) science fiction, about which I’ve written a series of posts for Gawker’s sci-fi blog io9.com. Our podcast’s inaugural episode is devoted to Radium Age mechanical and quasi-organic humanoids, which is to say, to ROBOTS.

Transcript of my introduction to the 1st episode:

The term “robot” was introduced in Karel Capek’s 1921 play R.U.R.: Rossum’s Universal Robots. The Czechoslovakian play, from which the TV show Dollhouse took the name of its sinister corporation, is set in a [probably American] factory of that mass-produces biological humanoids designed for blue-collar occupations. The term “robot” from the Czech word for “serf labor.” These days, however, we’d call Capek’s creatures “androids,” not robots. However, [Radium Age] science fiction is replete with our kind of robot: electricity-, steam-, and clockwork-powered machine-men who — like the Industrial Revolution from which they sprang — promised either to free us from the burden of labor… or else destroy or enslave us.

LISTEN TO (OR DOWNLOAD) THE PODCAST:

Parallel Universe: Pazzo (1) ROBOTS by HILOBROW

LISTEN TO (OR DOWNLOAD) AN EXCERPT:

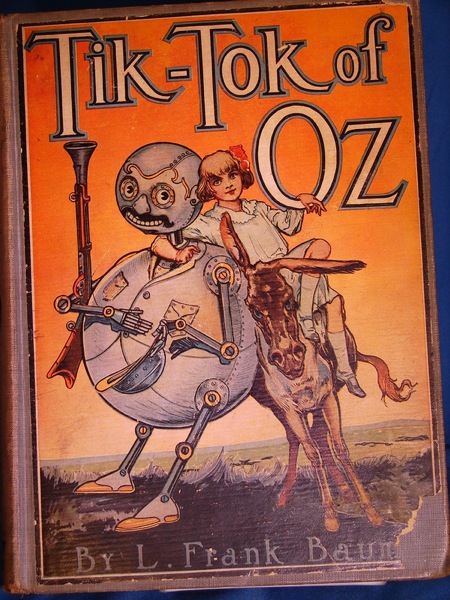

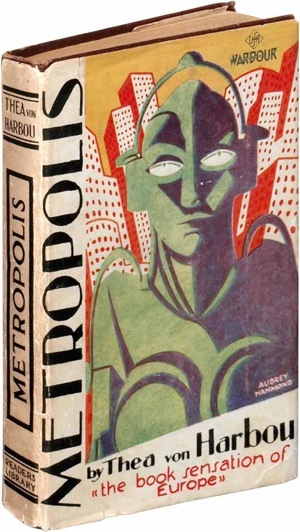

Matthew Battles reads: “The Jameson Satellite” (1931), by Neil R. Jones | Tom Nealon reads: “The Last Poet and the Robots” (1934), by A. Merritt | Tor Aarestad reads: “Moxon’s Master” (1909), by Ambrose Bierce | Ryan Mulcahy reads: Metropolis (1926), by Thea von Harbou | James Parker reads: “The Dancing Partner” (1893), by Jerome K. Jerome | Brian Nealon reads: Ozma of Oz (1907), by L. Frank Baum

EPISODE: “Parallel Universe: Pazzo” (1/ROBOTS)

HOST & PRODUCER: Joshua Glenn*

TALENT: Tor Aarestad, Matthew Battles*, Ryan Mulcahy, Brian Nealon, Tom Nealon, James Parker

THEREMIN: Peggy Nelson

THEME MUSIC, EPISODE 1: Sampled from DJ Spooky’s “Scanner/William S. Burroughs”

SPONSOR: Pazzo Used, Rare & Out-of-Print Books (Tom and Brian Nealon, proprietors)

PUBLISHER: HiLobrow.com

* HiLobrow.com’s editors

Bostonians — want to attend a recording session for the podcast? Get updates by becoming a “fan” of the show’s Facebook page. For dates, times, and directions, contact Tom and Brian Nealon at Pazzo Books.

We recently announced a short-short fiction contest, on the theme of “troubled and troubling superhumans,” which happens to be the theme of our podcast’s next episode. We’ll record that episode on February 26th, and include a dramatic reading of this contest’s winning entry. CLICK HERE for contest info.

I’ve named the years 1900-35 (roughly) the “Radium Age” of science fiction because the phenomenon of radioactivity — the discovery that matter is neither solid nor still and is, at least in part, a state of energy, constantly in movement — is a timely and fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, “vertigo years” during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered.

Why those dates, in particular? Not merely because the Curies won the Nobel Prize for their discovery of radium in ’03, while Marie Curie died (from radiation-induced leukaemia) in ’34. By my reckoning, the 19th-century era of Wellsian “scientific romances” ended between ’00 and ’03, while the so-called Golden Age of SF began between ’34 and ’37. The intervening three decades gave us American and European SF visionaries like Olaf Stapledon, William Hope Hodgson, Sax Rohmer, Karel Čapek, Hugo Gernsback, E.E. Smith, H.P. Lovecraft, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Yevgeny Zamyatin, Rudyard Kipling, Jack London, E.M. Forster, Arthur Conan Doyle, David Lindsay, David H. Keller, John Taine, Jack Williamson, S. Fowler Wright, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gustave Le Rouge, A. Merritt, Murray Leinster, Jean de La Hire, Maurice Renard, Garrett P. Serviss, and Philip Wylie. Not to mention Edgar Rice Burroughs and Aldous Huxley.

Science fiction’s so-called Golden Age began in the late 1930s, when John Campbell became editor of Astounding Stories and, eschewing space operas featuring babes in silver bikinis menaced by Bug-Eyed Monsters, instead began to solicit literate, analytical, and socially conscious “speculative fiction” from Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury, Arthur C. Clarke, and other writers we now consider the best of the best. As a result, science fiction writers who got their start in the post-H.G. Wells and Jules Verne era — roughly, between 1900 and 1935 — became personae non gratae. In his introduction to a 1974 collection titled Before the Golden Age, Asimov himself would note that although it may have possessed a certain exuberant vigor, in general pre-Golden Age [Radium Age] science fiction “seems, to anyone who has experienced the Campbell Revolution, to be clumsy, primitive, naive” — in a word, immature.

In the context of Cold War-era culture, the rhetoric of “maturity” cannot be taken as simply literary; it is also crypto-political. For example: at a 1952 Partisan Review symposium, Reinhold Niebuhr spoke for his fellow liberals and neocons when he rejected the widespread utopianism of the 1920s-30s as “an adolescent embarrassment.” The notion of “maturity” haunts the memoirs of anti-utopian intellectuals who’d been active at midcentury. If we no longer read Radium Age science fiction, it’s not because the era’s prose is adolescent in comparison with that of Golden Age science fiction authors. (Despite the assurances of influential SF critics like Kingsley Amis, it’s not true!) It’s because during the Cold War, we were encouraged to believe that every utopian vision is a totalitarian dystopia waiting to happen; this was a relentless message of much Golden-Age science fiction. But for earlier authors, whatever their politics, the medium of science fiction itself expressed a faith — one which I share — that another world is possible.

So “Parallel Universe: Pazzo” is a utopian (or, at least, an anti-anti-utopian) program, in one or more senses of “program.” We’re on a mission: to explore strange new paradigms; to seek out pre-1935 Lost Worlds, Supermen, Eco-Catastrophes, Telepaths, and Robots; to boldly podcast where no one has podcasted before.

More about the RADIUM AGE: CLICK HERE

COMPLETE FIRST EPISODE OF THIS PODCAST | MORE RADIUM AGE ROBOTS | MORE RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | MORE SCIENCE FICTION | MORE PODCASTS |