SEMIOPUNK (8)

By:

November 17, 2023

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

ODD JOHN

During World War I, British would-be writer Olaf Stapledon (1886-1950) served as a conscientious objector with a Quaker-funded ambulance unit, for which effort he was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Having returned home after the war to Liverpool, in 1925 he’d earn a doctorate in philosophy. Something of an idler (he’d later confess that he lived “chiefly on dividends and other ill-gotten gains”), he wouldn’t accomplish much of anything until 1929, when he’d publish A Modern Theory of Ethics: A Study of the Relations of Ethics and Psychology (1929). Here, he articulates his eccentric, progressive worldview, the elements of which include: moral obligation as a teleological requirement; ecstasy as a cognitive intuition of cosmic excellence; personal fulfillment of individual capacities as an intrinsic good; community as a necessary prerequisite for personal fulfillment; and the hopeless deficiency of human faculties when it comes to ascertaining the meaning of life, the universe, and everything.

The following year, Stapledon would publish the Radium Age proto-sf novel Last and First Men, a breathtakingly epic history of the future (apocalypse after apocalypse) and meditation on the present, which he depicts as a tragic era during which only a few sensitive, and therefore hapless and hopeless individuals can even catch a glimpse of the possibility of what we might describe as cosmic consciousness. Which is to say: a comprehensive and analytical vision of everything that exists as perceived by someone who has mutated and/or eveolved to the point where the congenital deficiencies of the ordinary human being are at last overcome. The story is narrated — telepathically, to the “scarcely adequate brain” of one of the First Men, which is to say one of us — by one of the Last Men, Neptune-based descendants of humankind’s, from the future, two billion years hence.

What does fate hold in store for us First Men? The post-WWI “passionate will for peace and a united world” won’t last long, Stapledon’s narrator informs us. Within a century aerial bombs and poison gas will have laid waste to Europe and Russia, leaving the Chinese and Americans to compete for global military-economic domination. Eventually, a World State will be founded, and peace and prosperity will reign… until Earth’s natural energy sources get used up! At that point, civilization will collapse and the First Men will devolve into superstitious savages living in the shadow of their ancestors’ skyscrapers — “though for the most part they were of course by now little more than pyramids of debris overgrown with grass and brushwood” — until, after nearly 100,000 years, they’ll re-civilize themselves and discover atomic energy. After “a bout of insane monkeying with the machinery,” all but 35 men and women, whose mutated descendants will be the Second Men, are annihilated. This sort of thing goes on for 18 generations.

Although he wasn’t himself much of an sf aficionado (he described his stories as “fantastic fiction of a semi-philosophical kind”), Stapledon was hailed as one of the emerging sf genre’s bright lights by H.G. Wells, as well as by such highbrow modernist litterateurs as Jorge Luis Borges, Bertrand Russell, and Virginia Woolf. This first novel, which caused something of a literary sensation at the time, has since fallen into complete obscurity.

In 1932, Stapledon would publish another Radium Age proto-sf yarn, Last Men in London. This is the story of Paul, a teacher telepathically possessed by a member of an evolved human species (the Last Men) living in the distant future, and one of Paul’s students: “Humpty,” a London teenager and “supernormal” — in whom there is “some promise of a higher type.”

As adolescents, the reader is led to believe, all “submerged supermen” like Humpty (whose nickname refers to his oversized cranium) are misfits: they don’t take themselves seriously, they don’t want to get ahead, they despise athletics, they’re puzzled and bored by religion and patriotism, they don’t regard sexuality as shameful, and they remain idealistic long after childhood.

Humpty outlines a plan to found a new human species — one that will control the world and eliminate or domesticate the “subhuman hordes”; however, luckily for the rest of us, he succumbs to despair.

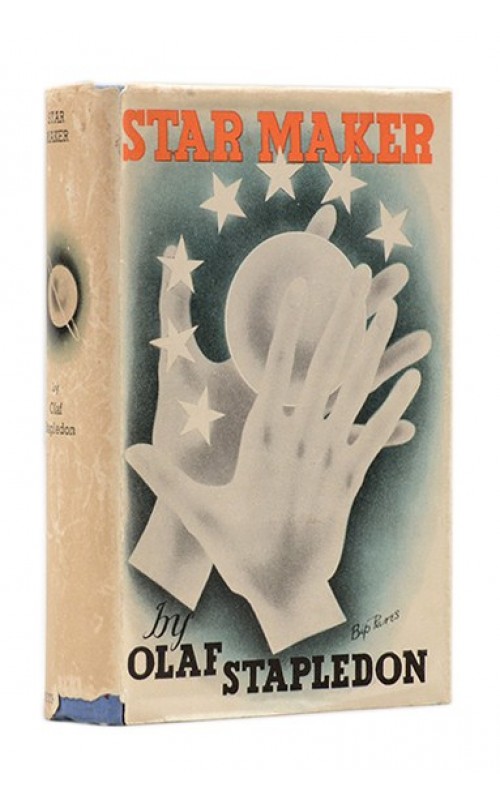

The Golden Age sf novel Star Maker (1937), often regarded as his greatest work, represents the climax of Stapledon’s so-called Future History/Last Men sequence.

This extraordinary, brilliant (if often difficult) novel describes a history of life in the universe, while exploring the philosophical notion that between different civilizations, no matter how physically and mentally dissimilar they may be, there must exist a progressive unity. Via unexplained means, our narrator is transported from England — and out of his body — into space. Over a timespan which extends to 100 billion years, he explores alien civilizations on other worlds — and his consciousness merges with that of beings from these worlds, who then join him on his journey around the universe. Like humankind, we discover, alien species evolve in a Darwinian manner, and possess a capacity to value, to be aware, and to be creative.

In addition to imaginative descriptions of species, we encounter far-out technological marvels and sci-fi concepts: the first known instance of what is now called the Dyson sphere; early descriptions of the Multiverse; the idea that the stars are intelligent beings; the formation of a networked consciousness spanning planets, galaxies, and even the cosmos; and a Star Maker who creates the universe — but views it without any feeling for the suffering of its inhabitants. The Science Fiction Encyclopedia suggests: “Its cosmic range, fecundity of invention, precision and grandeur of language, structural logic, and above all its attempt to create a universal system of philosophy by which modern human beings might live, permit cautious comparison [between Stapledon’s Star Maker and] Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy” — the protagonist of which also becomes a “disembodied, wandering viewpoint.”

PS: The posthumously discovered “Nebula Maker” (1976), apparently written in the mid-1930s as part of an early draft for Star Maker and then put aside, shows how the striving of conscious nebulae is brought to nothing by an uncaring God.

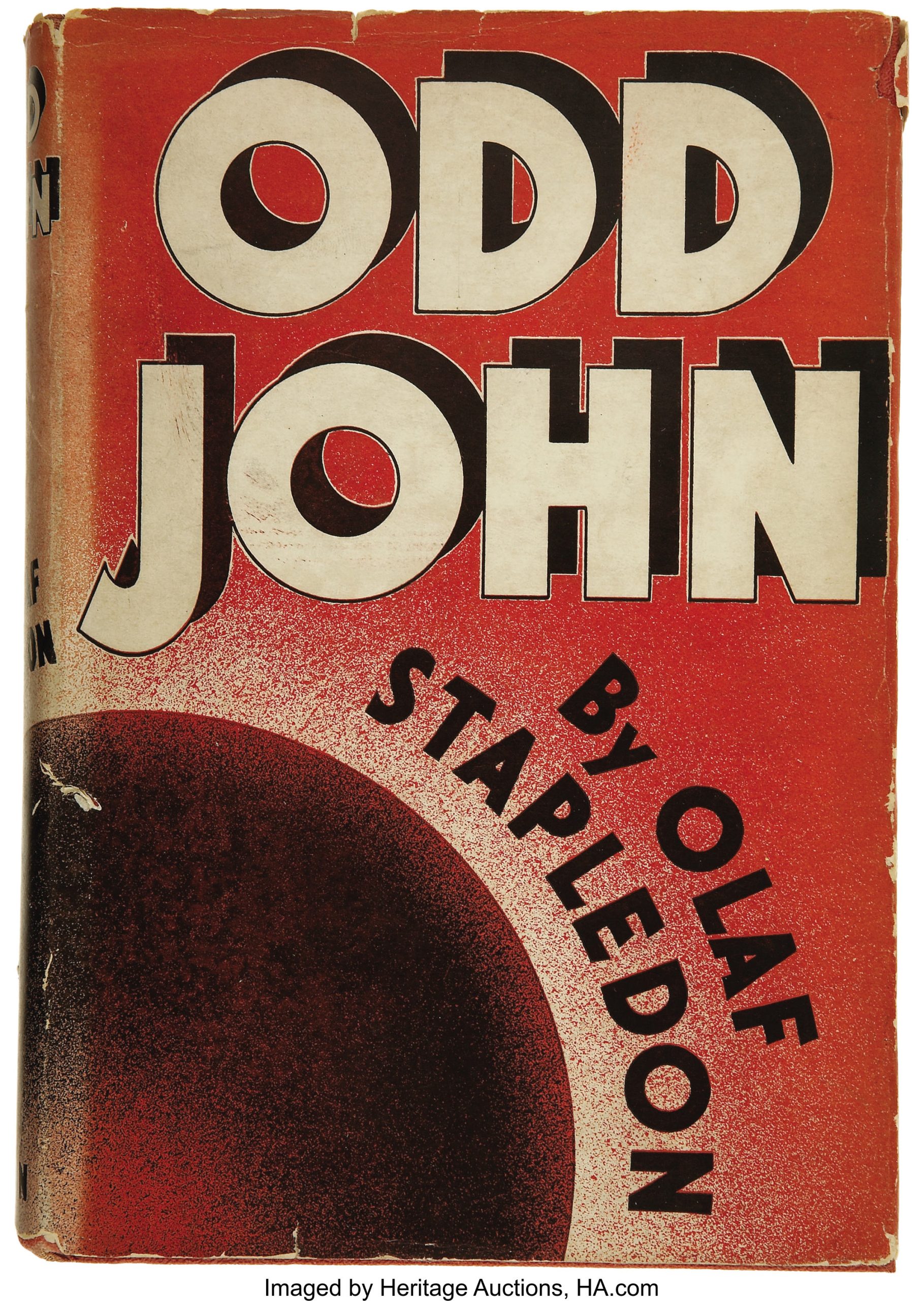

Which brings us to Odd John (1935). Published between Last Men in London and Star Maker, exactly on the cusp between the science fiction genre’s Radium Age (c. 1904–1933 in my original periodization; c. 1900–1935 in my current periodization) and its so-called Golden Age (c. 1934–1963).

Here we find more teenage mutant “supernormals” or “wide-awakes” — misfits who don’t want to get ahead, despise athletics, find religion and nationalism boring, don’t regard sex as shameful, and remain idealistic and utopian long after adolescence. Led by Odd John, these teen titans, each of whom possesses a different superhuman ability, form an island colony. Here, they experiment with telepathic communication, free love, “intelligent worship,” and “individualistic communism.”

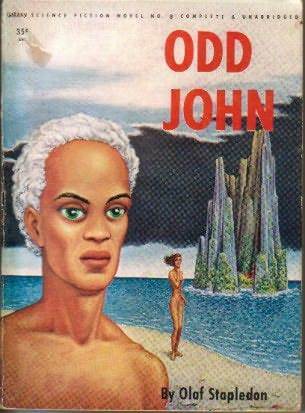

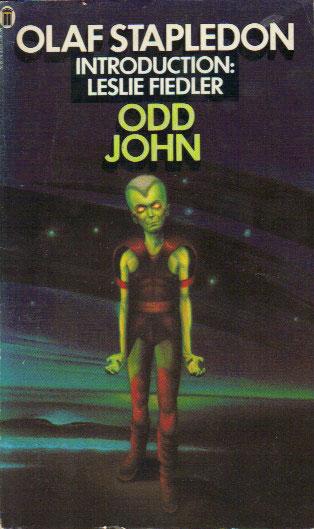

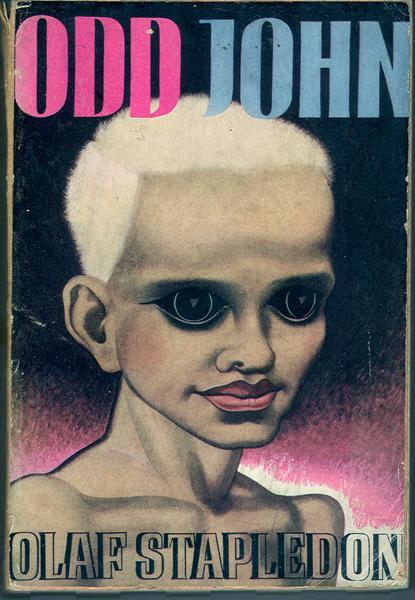

This novel is credited with giving us the expression homo superior, later popularized by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s X-Men comics. A couple of the period jacket illustrations shown here capture Stapledon’s notion of the titular John: half-child and half-philosopher, ruthless yet not malicious, “a creature which appeared as urchin but also as sage, as imp but also as infant deity,” a fallen angel with a face that is “half monkey, half gargoyle, yet wholly urchin, with its huge cat’s eyes, its flat little nose, its teasing lips.” Cue David Bowie: “Look at your children/See their faces in golden rays/Don’t kid yourself they belong to you/They’re the start of a coming race.”

This is a bildungsroman of sorts, in which we observe John learn to speak, count, master all of mathematics, and develop an ability to visualize n-dimensional space — all before the age of five. Unlike Victor Stott, the superhuman child character in J.D. Beresford’s The Hampdenshire Wonder (1911), John learns to defend himself. He studies society, culture, the economy — all from an outsider’s perspective.

When young John is studying biology, he suddenly tires of it. An adult character asks, “Have you finished with ‘life’ as you finished with ‘number?'”

“No,” replied John, “but life doesn’t hang together like number. It won’t make a pattern. There’s something wrong with all those books. Of course, I often see they’re stupid, but there must be something deeper wrong too, which I can’t see.”

John is a pattern-seeker, and a pattern-maker:

He devised strange shapes which epitomized for him the tragedy of Homo sapiens, and the promise of his own kind. At the same time he was allowing the perceptual forms with which he was surrounded to work themselves deeply into his mind. He accepted with insight the quality of moor and sky and crag. From the bottom of his heart he gave thanks for all these subtle contacts with material reality; and found in them a spiritual refreshment which we also find, though confusedly and grudgingly.

He not only perceives unseen patterns and forces that are imperceptible to the rest of us; he is deeply affected by them too.

Sometimes he would listen intently to people’s voices; but not, apparently, for their significance, simply for their musical quality. He seemed to have an absorbing interest in perceived rhythms of all sorts. He would study the grain of a piece of wood, poring over it by the hour; or the ripples on a duck-pond. Most music, ordinary music invented by Homo sapiens, seemed at once to interest and outrage him; though when one of the doctors played a certain bit of Bach, he was gravely attentive, and afterwards went off to play oddly twisted variants of it on his queer pipe. Certain jazz tunes had such a violent effect on him that after hearing one record he would sometimes be prostrate for days. They seemed to tear him with some kind of conflict of delight and disgust.

It’s this sort of material that leads me to categorize Odd John as an early work of semiopunk sf.

Like most Radium Age supermen, John is a benignant character — not entirely malignant, but not entirely benevolent, either.

Early on, it becomes evident that like Nietzsche’s overman, John has not internalized human morality; when he swings, if you will, he hangs past right and wrong. He becomes a libertine and worse, though soon enough he tires of this style of life and instead develops an austere spirituality. Once having developed the power of telepathy, he uses it — like Professor X will, later — to seek out fellow mutants, including a 12-year-old Ethiopian boy, a 17-year-old Siberian girl, and a medieval superhuman who has died — but with whom John is capable of communicating. Far out!

John’s island colony, which puts into action some of the principles Stapledon had outlined in his A Modern Theory of Ethics, is for a while safe from the outside world — protected, as it is, by its inhabitants’ psionic abilities. The novel’s narrator, who has observed John growing up, and is the only un-evolved human permitted to visit the island, isn’t sure whether to be overjoyed or terrified about what the “wide-awakes” are planning.

When the world’s Great Powers join forces to conquer Odd John’s utopia, what will John do?

Fun fact: According to the SFE, Stapledon’s “influence, both direct and indirect, on the development of many concepts which now permeate genre sf is probably second only to that of H. G. Wells.”

Please note that if you click on the links above, you’ll discover that — in the course of researching and writing my Best Adventures project — I’ve named Stapledon’s novels as being among the best proto-sf, sf, and adventure novels of the twentieth century.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.