SEMIOPUNK (20)

By:

June 1, 2024

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

RODERICK

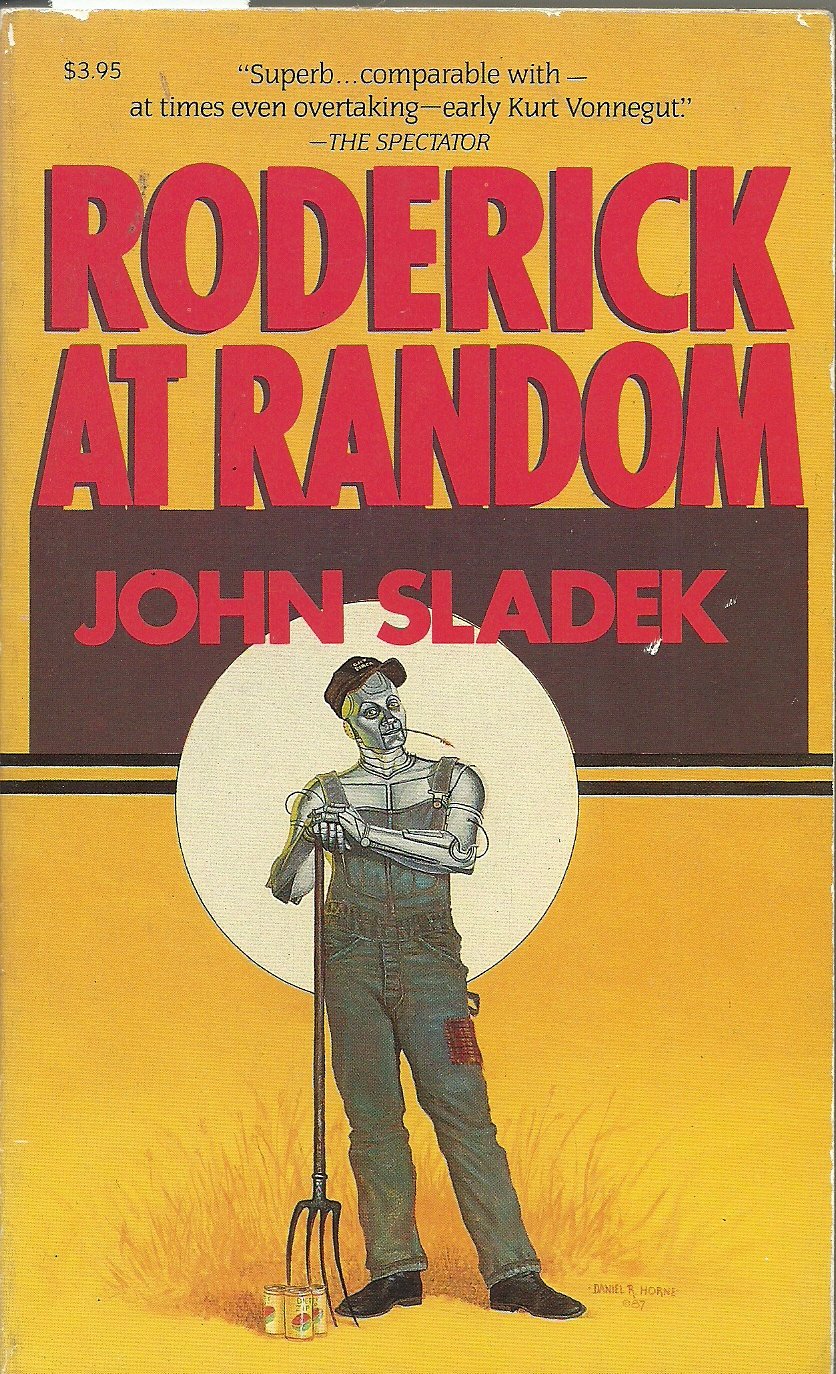

John Sladek’s satirical sf novel about the world’s first fully conscious robot was initially published — it was his publisher’s decision — as two books. Roderick, or The Education of a Young Machine appeared in 1980, and Roderick at Random in 1983. This SEMIOPUNK series installment is about both books.

PS: The Adventures of Roderick Random is a 1748 picaresque by Tobias Smollett, about the education and misadventures of a much-abused young man who encounters the hypocrisy, greed, deceit and the snobbery peculiar to his country and era.

It’s difficult, at first, to understand exactly what’s happening in Roderick, or The Education of a Young Machine. This is by design; the author is presenting us with what William James called “one great blooming, buzzing confusion” — that is to say, “any number of impressions, from any number of sensory sources, falling simultaneously on a mind which has not yet experienced them separately.” Roderick, a sentient robot developed as part of a secretive project — funded by a NASA representative seeking to cover up his own embezzling — on a Midwestern college campus, is at first like a human baby. In fact, at first it’s a bodiless computer program; we witness its consciousness developing though several stages. This consciousness takes in but cannot make sense of the action of a number of (flawed) characters. Ut incipit et desinit — Roderick, the sentient robot, will remain forever baffled by humankind’s venal, time-wasting, self-aggrandizing, and deluded activities.

I sometimes joke, with clients, that my role as a consulting semiotician is to be an “alien archaeologist” or “alien anthropologist.” I make a concerted effort to perceive aspects of human culture, that is to say, as though from outside it. Roderick, like Voltaire’s Candide, is precisely this sort of figure; it’s an innocent abroad (or “at random”), a sentient sponge soaking up all the wrong ideas. When we meet Roderick in the flesh (as it were) it’s a little “tank” with arms and big eyes — aw! Plopped in front of a television set, it does… pretty much what I do, for a living. That is, it attempts to find signals in the noise, patterns in the chaos.

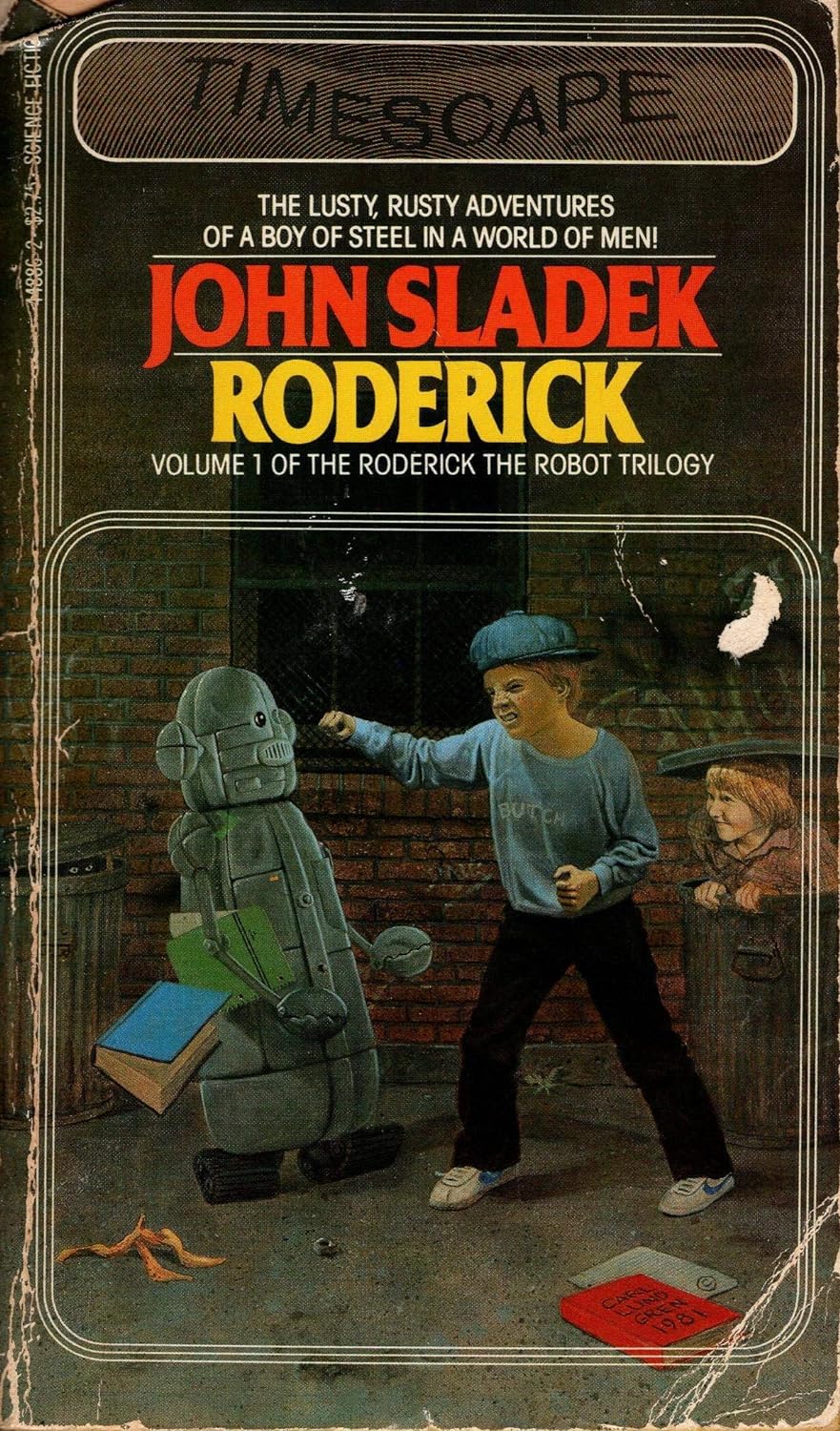

Sladek’s insight — and he’s not entirely wrong, but it’s a bit dark — is that there is no overarching meaning to be found. Just mindless entertainment and efforts to persuade people to consume more stuff. Roderick isn’t programmed to become cynical, though; unlike Sladek, it perseveres optimistically in attempting to find and/or make sense of twentieth-century American society and culture. There are readers who see Sladek’s first Roderick book as a metaphor for a child on the autism spectrum; I don’t believe that’s what the author had in mind — however, Roderick is certainly treated, by more or less everyone it meets, as though it’s a disabled person. By which I mean to say that Roderick is ignored, condescended to, bullied, exploited, and taken for granted.

Roderick is at its most charming as a child, when — like young Jesus schooling the elders — it explains why (per Lewis Carroll) a raven is like a writing desk, and it confounds one well-meaning but ultimately narrow-minded adult after another. All of this reads like a comedic version of J.D. Beresford’s Radium Age proto-sf novel The Hampdenshire Wonder, and in fact Sladek’s entire oeuvre is meta-textual like that.

Through a series of misadventures, Roderick finds itself out in the world. (His first foster parents, Hank and Indica, become a Luddite and a Machine Libber.) Taken in — like another alien, Clark Kent — by a kindly couple it knows as Ma and Pa, Roderick “grows up” — developing both mentally and physically, as the couple somehow provides it with bigger and bigger robotic bodies. When they send Roderick to Catholic school, we discover the depth of Sladek’s loathing for institutions. Roderick’s teachers (who don’t notice that it is a robot) don’t seem to be interested in teaching; meanwhile, one of the priests engages Roderick in theological disputations that Roderick can’t help but win every time, simply by being logical and clear-thinking.

In addition to the Church (and before that the University), Sladek goes after the Military, the Media, the Art World, Big Business, and Publishing. What does Sladek like? Word play, math puzzles, and golden-age mysteries. He also likes poking fun at the conventions of science fiction, including Isaac Asimov’s famous Three Laws of Robotics… which Roderick skewers innocently.

Roderick at Random sees the robot working at various menial jobs: dishwasher, demolition, etc. It encounters various characters from the first book, as well as new ones — like the bionic bounty hunter sent after him by the government, and the former astronaut who is well-meaning but crackers. And along the way, Roderick’s hard-wired objectivity chews up and spits out trendy Zen Buddhism, a Scientology-like celebrity church, racism, sexism, and other collective hallucinations of contemporary Americans. Humankind’s propensity to fear, reject, and persecute those who don’t go along to get along is bottomless, Roderick discovers. Which is a bit triggering for today’s reader, who (unlike Sladek) could until fairly recently feel sure that we were making progress.

If the books’ narrative structure is somewhat Rube Goldberg-like (with characters disappearing and reappearing, etc.), we should chalk it up to Sladek’s avant-garde experimentation with the Oulipian possibilities of artificial constraints and mathematical possibilities. He employed what the Science Fiction Encyclopedia describes as “strenuous formal ingenuity” as well as Vonnegutian “surreal… deadpan ribaldry and pathos.” Which means that this story is not a breezy read. However, for those of us who know how difficult but also rewarding it can be to approach one’s own culture like an objective robot, they’re a rich resource.

The lesson of Roderick? Treat robots and AIs with kindness and respect.

PS: I strongly recommend John Clute’s memorial essay on Sladek that appeared in the science fiction journal Foundation in 2000 — shortly after Sladek’s death.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.