SEMIOPUNK (9)

By:

December 18, 2023

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

TIME OUT OF JOINT

“I am a fictionalizing philosopher, not a novelist,” one reads in The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick, a selection of journal entries in which PKD documents and analyzes his religious and visionary experiences. He goes on to claim: “I am basically analytical, not creative; my writing is simply a creative way of handling analysis.”

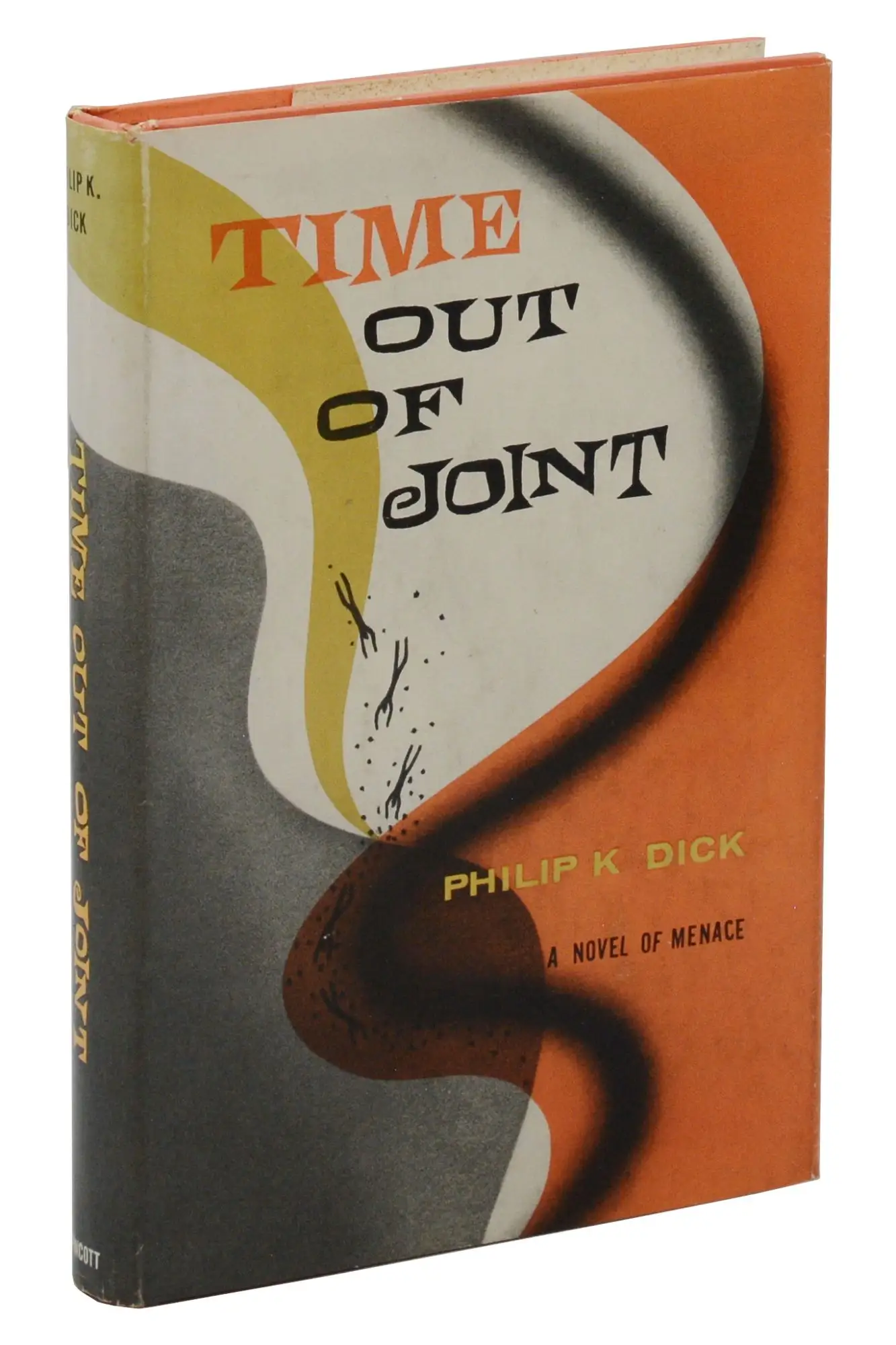

Dick had great hopes for the success of Time Out of Joint, published in 1959 not as a work of science fiction but rather as a “novel of menace.” By telling the story of Ragle Gumm, a seemingly ordinary fellow who discovers — as his Fifties suburb begins to dissolve around him, that it’s actually 1994… and that the government may be employing a large-scale illusion to keep him pacified — he hoped to break out of what he perceived as the sci-fi ghetto and achieve recognition as a fictionalizing philosopher. Alas for him, Time Out of Joint didn’t sell well.

Dick’s influence, of course, has continued to grow — it really began to take off in the ’90s. Today, Dick’s neo-gnostic notion — which he explored from a variety of angles across his many writings, and which the Exegesis suggests that he more or less believed — that “reality is a pernicious illusion,” to quote a Simon Critchley essay on Dick, “a repressive and authoritarian matrix generated in a dream factory we need to tear down in order to see things aright and have access to the truth” is arguably (per Critchley) “the dominant mode of understanding of fiction in our time, whether literary, artistic or cinematic.” This seems a little overblown… but only a little.

A minimally sci-fi novel about false reality, Time Out of Joint is a key turning point in Dick’s oeuvre. Note that it appeared in 1959 — the apex, in HILOBROW’s periodization schema — of the cultural era known as the Fifties. Let’s revisit its plot.

Ragle Gumm lives with his sister and her husband in a quiet suburb. He earns a living by winning — again and again — a local newspaper contest, “Where Will The Little Green Man Be Next?” (Fans of Ender’s Game — one has to imagine that this is where Orson Scott Card pilfered the idea for that story.) When odd — semiotically odd — things start happening — notably, a soft-drink stand turns into a slip of paper that reads “SOFT-DRINK STAND”; Gumm becomes persuaded that the bathroom has a pull-cord light, even though it has always had a wall switch (Dick would claim that this happened to him in real life, and was the source of inspiration for the novel) — Gumm at first suspects he may be having a nervous breakdown. But his brother-in-law begins to notice reality-discrepancies, too. When the two men try to leave town, there’s always something that traps them there. (Fans of The Truman Show, yep, here’s where that idea came from…)

In the works of certain philosophers, we read that the phenomenal realm is the highly differentiated, external world of material objects as we humans experience it with our senses; it is a representation of the mind, that is, in which space, time, and causality define our perceptions. The noumenal realm, meanwhile, is a single, undifferentiated entity – the thing-in-itself – that is spaceless, timeless, non-material, and beyond the reach of causality. It is inaccessible to direct experience. According to Schopenhauer’s gloss on the idea, phenomenon and noumenon are the same reality apprehended in two different ways: the noumenon is the inner significance, the true but hidden and inaccessible essence, of what we perceive outwardly as the phenomenal world. Semiotics, too, is concerned with the inner significances of the everyday world.

Here’s a quote from Daniel Chandler’s Semiotics: The Basics…

Semiotics is important because it can help us not to take “reality” for granted as something having a purely objective existence which is independent of human interpretation. It teaches us that reality is a system of signs. Studying semiotics can assist us to become more aware of reality as a construction and of the roles played by ourselves and others in constructing it. It can help us to realize that information or meaning is not “contained” in the world or in books, computers or audio-visual media. Meaning is not “transmitted” to us — we actively create it according to a complex interplay of codes or conventions of which we are normally unaware. Becoming aware of such codes is both inherently fascinating and intellectually empowering. We learn from semiotics that we live in a world of signs and we have no way of understanding anything except through signs and the codes into which they are organized. Through the study of semiotics we become aware that these signs and codes are normally transparent and disguise our task in “reading” them. Living in a world of increasingly visual signs, we need to learn that even the most “realistic” signs are not what they appear to be. By making more explicit the codes by which signs are interpreted we may perform the valuable semiotic function of “denaturalizing” signs. In defining realities signs serve ideological functions. Deconstructing and contesting the realities of signs can reveal whose realities are privileged and whose are suppressed The study of signs is the study of the construction and maintenance of reality. To decline such a study is to leave to others the control of the world of meanings which we inhabit.

The exciting but vertiginous, uncanny speculations that we find fictionalized in multiple PKD novels from Time Out of Joint on are semiotic in nature.

What might it be like if we could perceive reality, even momentarily, without filters? And also: Are filters imposed upon us by a malign authority for a sinister purpose?

Fredric Jameson’s Postmodernism: Or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism includes a brief analysis of how Time Out of Joint — in which Gumm believes he is living in the 1950s — when in fact he may be living in a reconstruction of that era based on stereotypes about the decade — helps us to understand how America’s dominant discourse has successfully obscured the realities of the 1950s behind “the representation of that rather different thing, the ‘fifties;’ a shift which obligates us in addition to underscore the cultural sources of all the attributes with which we have endowed the period, many of which seem very precisely to derive from its own television programs; in other words, its own representation of itself.”

“The empire,” to quote Dick, “never ended.”

Like most of PKD’s protagonists, Gumm is bewildered, aliented, frightened… yet stubborn. He won’t cease in his efforts to understand what’s going on. Are most aspects of his life staged, in order to keep him focused on the “Where Will The Little Green Man Be Next?” quiz? (Because, say, his answers to the quiz help Earth’s planetary defense forces — in 1998 — predict the movements of rebel lunar colonists?) And if so, is what he’s actually doing critically important to humankind… or might he be helping to keep a tyrannical social order in place? (Fans of The Matrix…)

Forget Tom Cruise, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Harrison Ford, and other actors who’ve portrayed PKD protagonists. At the apex of the conformist Fifties, the closest thing to a hero that we can expect is a “minor man” (as Dick would put it in an essay) striving to see things as they really are, struggling to resist normative reality and the dominant discourse however possible, “in all his hasty, sweaty strength.”

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.