INTO THE GROVE (7)

By:

March 23, 2017

One in a series of posts, by long-time HILOBROW friend and contributor Brian Berger, celebrating perhaps America’s most exciting and controversial publisher: Barney Rosset’s Grove Press.

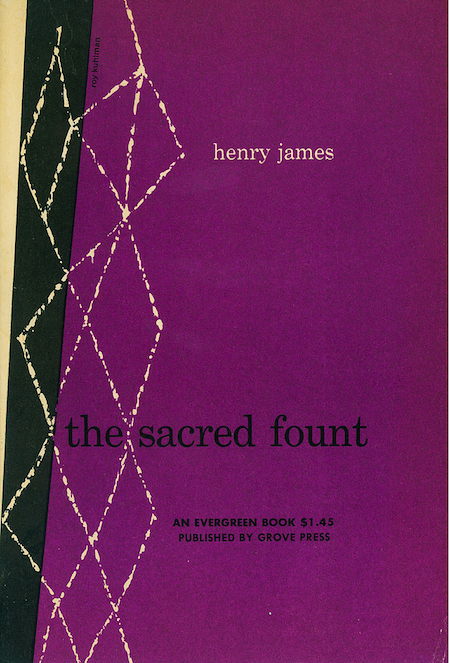

Henry James’s The Sacred Fount, introduction by Leon Edel (1901, 1955)

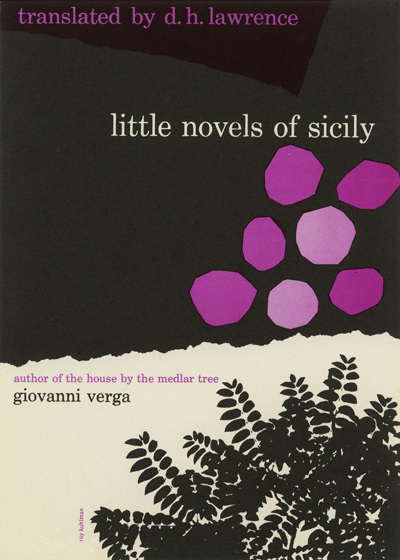

Giovanni Verga’s Little Novels of Sicily (1925, 1955) translated by D.H. Lawrence

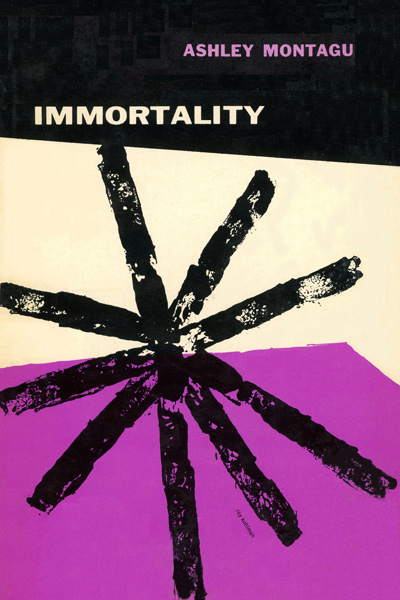

Ashley Montagu’s Immortality (1955)

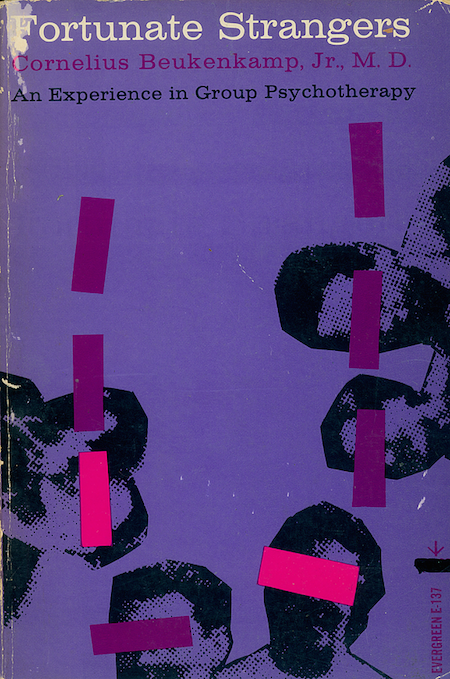

Cornelius Beukencamp Jr.’s Fortunate Strangers: An Experience in Group Psychotherapy (1958, 1959)

Ernest Jones’s On the Nightmare (1931, 1959)

Herman Melville’s Pierre, or The Ambiguities (1852, 1957)

All cover designs by Roy Kulhman.

“Purple and black, a heavy harmony. Purple and white, a cold harmony.” — Foundations of Success and Laws of Trade (1883), D.R. Shafer and J.A. Dacus editors

“If there is anything in fiction that is more tantalizing, more exasperating, yes, more maddening,” began the Brooklyn critic in February 1901, “than the last novel of Henry James The Sacred Fount (Scribner), I hope to be spared it. And yet there is some strange fascination attaching to the book that would attend one’s efforts to read the puzzling and contradictory character of an interesting acquaintance. On its face, if anything so esoteric can be said to have a face, Mr. James’s book presents a study of two intellectual vampires, so to speak, with equally subtle and minute portraits of their victims. ‘Poor Briss’ has laid his youth and gayety of spirits on the marriage altar and Mrs. Brissendon, many years his senior…”

The critic, like James himself, goes on, not uninterestingly, but what if, vampirism aside, in lacking a language for its public discussion, The Sacred Fount is actually a novel of gayness?

First published in Italy in 1883, Little Novels of Sicily is one of three Grove Press titles by the Catania-born Giovanni Verga (1840-1922). Thinking of Apuleius and Sancho Panza and also the words of another eminent Sicilian, Empodocles (c. 484-424 BC), here on reincarnation — “In the past I have been a boy and a girl, a bush, a bird and a dumb water-dwelling fish” in Philip Wheelwright’s rendering from the Greek — I was immediately drawn to Verga’s tale “The Story of St. Joseph’s Ass,” which in the translation of D.H. Lawrence begins:

“They had bought him at the fair at Buccheri when he was quite a foal, when as soon he saw a she-ass he went up to her to find her teats; for which he got a good many bangs on the head and showers of blows upon the buttocks, and caused a great shouting of ‘Gee back!’ Neighbor Neli, seeing him lively and stubborn as he was, a young creature that licked his nose after it had been hit, giving his ears a shake, said ‘This is the chap for me!’ And he went to the owner, holding in his pocket his hand which clasped the eight dollars.”

They don’t make social biologists like Ashley Montagu (1905-1999) anymore and even if “they” did, how would “we” know about it? Already the author of Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race (1942) and another radical work, provocatively titled The Natural Superiority of Women (1953), Immortality was originally presented as a series of three lucid but densely allusive lectures at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in March 1951. The theme is death and — though I wish not to spoil the ending — there aren’t many laughs along the way. In between the lectures and their publication in book form there were some changes which Montagu footnoted for posterity. One example follows.

Text: “The idea of ultimate complete annihilation of this world is something most human beings have found both inconceivable and intolerable.”

Footnote: “That is, in the pre-atom bomb world. In the world of the hydrogen and cobalt bombs, human beings no longer find the idea of complete annihilation of this world either inconceivable or intolerable. Most persons have adapted an attitude of resignation to the inevitable — whatever it may prove to be. Such apathy is more dangerous than any atom bomb.”

“What really happens in group psychotherapy?” asked the advertising copy in February 1958.

Four men and four women — a passionate, tragic, irritating, pathetic group — learned together to face the problems that each had been unable to face alone. For fifteen stormy months, these Fortunate Strangers met, gradually learning, for the first time, to relate to their own lives and those of other people… This book tells about:

- Eve, who sought fulfillment in sex

- John, shattered by the knowledge of his father’s abnormality

- Claudia, who found her husband to be a homosexual

- Tom, who hated the world because he hated himself

- and the others, who exposed their problems to the group.

Not previously knowing the eminent Welsh-born Freudian Ernest Jones (1879-1958) I thought On the Nightmare might be a book of poems, so rhythmic, bright and jaunty is Roy Kuhlman’s design. But no; Jones’ work is about exactly what its title says, the terror of sleep, including many werewolves. If not the actual source of American songwriter Michael Hurley’s eternal “Werewolf,” Jones usefully explains the subject’s lasting primal power.

In May 1956, Harvey Breit of the New York Times interviewed the 77-year-old psychoanalyst and author in a Manhattan hotel room. There remained many demands on Jones’ time — his recently completed three volume biography of Freud was a publishing sensation — and if weary, Jones wasn’t unengaged.

“Haven’t been out all day,” he said. He sank back in his chair. “All day — people.” He held a dead, half-smoked cigarette in is hand. I offered him a fresh one. “What’s that? What kind is that?” He asked in his clipped, ironic way. I told him it was a filter. “That to prevent cancer?” He took the cigarette anyway.

In August 1852, Harper & Brothers placed a small classified ad noting the publication of Herman Melville’s Pierre but the newspaper, the New York Times, did not review it. Across the river, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle likewise ignored the novel until January 1853, when in thoughtlessness, or malice, or maybe simple self-amusement it noted:

The London Athenaeum savagely reviews Herman Melville’s Pierre, saying among other things the following: “Its plot is amongst the most inexplicable ‘ambiguities’ of the book — the style is a prolonged succession of spasms — and the characters are a marrowless tribe of phantoms, flitting through dense clouds of transcendental mysticism.”

More than a century later, Allen Ginsberg would call Pierre a great prose poem and quote its final line from memory: “And her whole form sloped sideways, and she fell upon Pierre’s heart, and her long hair ran over him, and arboured him in ebon vines.” Does that mean Pierre is gay? Some opine the gayest.

NB: For the likelihood of coded homosexuality in The Sacred Fount, see the indefatigable Adeline R. Tintner’s The Twentieth Century World of Henry James: Changes in His Work After 1900 (2000). On similar ground, James Creech’s Closet Writing / Gay Reading: The Case of Melville’s Pierre (1994) is equally revelatory.

BOOK COVERS at HILOBROW: INTO THE GROVE series by Brian Berger | FILE X series by Josh Glenn | THE BOOK IS A WEAPON series | HIGH-LOW COVER GALLERY series | RADIUM AGE COVER ART | BEST RADIUM AGE SCI-FI | BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI | BEST NEW WAVE SCI-FI | REVOLUTION IN THE HEAD.