America Obscura (6)

By:

November 16, 2016

HILOBROW friend Andrew Hultkrans is a legendary freelance journalist; we have admired his range, erudition, and virtuosity since the early ’90s, when he was a columnist at MONDO 2000. We’re proud to publish this series of essays by Andrew, each of which originally appeared (as noted) elsewhere.

Same Old Song?

The Rose and the Briar: Death, Love, and Liberty in the American Ballad, edited by Sean Wilentz and Greil Marcus (Norton).

Few things in this world are both scary and boring, but two American icons fit the bill: the neocon and the balladeer. Dick Cheney, for one, could benumb a Super Bowl audience while announcing North America’s thermonuclear demise. Likewise, certain ballad singers—Joan Baez comes to mind—have a knack for turning tales of grisly homicide into lullabies. That some of this country’s more famous balladeers would be better employed in insomnia wards doesn’t mean the American ballad itself is dull, however. Quite the contrary. Before Hollywood, Rupert Murdoch, and the Weekly World News, the American ballad was the go-to source for stories of lurid murders, demon lovers, femmes fatales, wrecks, floods, plagues—even, as in “Barbara Allen,” rose and briar bushes sprouting from the skeletons of buried sweethearts, the image that this omnivorous anthology of ballad-inspired essays, fiction, and art takes for its title.

A ballad is a story-song, usually detailing slayings, betrayals, illicit affairs, historic disasters, nefarious criminals, irresponsible engineers, or, in one regionally specific case, the serial crop-killing spree of the boll weevil. Long before rap became, as Chuck D put it, “the black CNN,” the ballad was the folk CNN—a century-spanning, intercontinental game of telephone, carrying the news of the day to eras and regions far beyond its original period and locale, with names, verses, and plot points remixed to suit whomever might be singing at the moment. The oldest American ballads, like “Barbara Allen,” floated to these shores from England, Ireland, and Scotland, some of them dating as far back as medieval times. Once planted, these ballads grew like creeping vines, entwining themselves with local events, figures, and legends as intimately as the rose and briar stems growing from Sweet William and Ms. Allen’s graves, spawning hybrids whose roots could barely be traced. The durability of the form led to native varietals, truly American ballads that may have borrowed a melody, a line, or a cadence from across the Atlantic but drew their subjects from purely domestic sources.

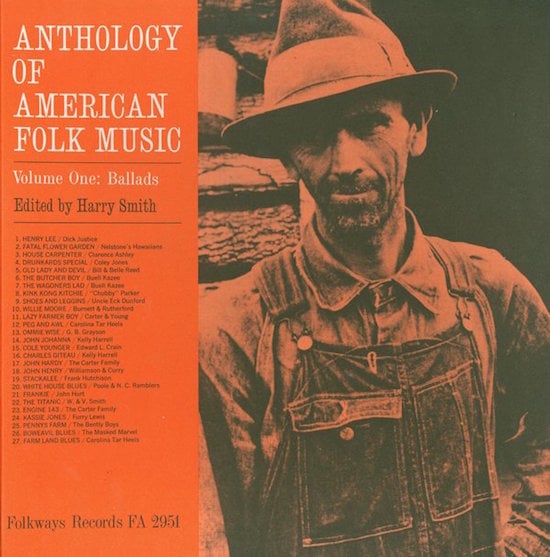

Nineteenth- and twentieth-century musicologists, such as Frances Child, Cecil Sharp, and John and Alan Lomax, exhaustively documented the old ballads and their myriad lyrical mutations, but no one (outside of the Lomaxes) did more to codify and disseminate the recorded American ballad than Harry Smith, who parsed his 1952 Anthology of American Folk Music into three volumes: “Ballads,” “Social Music,” and “Songs.” Smith’s taxonomy presented new generations of musicians with aural evidence of the ballad/song divide—evidence that, along with the emergence of rock ’n’ roll and the nightly news, contributed to the slow decline of the ballad as a popular American form.

Some definitions: Many “folk songs” of the Pete Seeger variety are ballads; most blues are songs. “Hotel California” is a ballad; “California Girls” is a song. “Gangsta Gangsta,” from N.W.A.’s Straight Outta Compton, is a ballad, the rake’s progress of a modern Stagolee, narrated by his own bad self; the title track, a tripartite rant on the theme of badassitude, is a song. Johnny Cash’s “Long Black Veil” is a ballad; Bob Dylan’s “Man in the Long Black Coat” is a parody of a ballad.

Unlike the linear ballad, the song is an exquisite corpse, a Frankenstein’s monster of verse parts exhumed from disparate traditions and sutured into a reanimated whole. The first cut Harry Smith chose for his “Songs” collection, “The Coo Coo Bird,” epitomizes this anti-form. As performed by Clarence Ashley, “The Coo Coo Bird” strings together ornithological factoids, international card-sharp bravado, and a mountainside architectural venture to observe one “Willie,” a frequent passerby. Like all great songs, “The Coo Coo Bird” resists interpretation. Its cryptic, unrelated verses leave gaps that the mind tries, preconsciously, to fill. Through its refusal to stand on ceremony, to offer up meaning, to tell a story, a song summons the uncanny and makes you uncomfortable. You keep listening because you don’t know what it’s saying. In short, the song absolves the singer of the need to make sense. You can be a lizard in the spring in one verse and express concern over your wife’s hairdo in the next, all under a that-clears-it-up rubric like “I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground.” Very freeing, the song. As a songster, you’re simply allowed to be a Lizard-Mole-Man, coming over the hill with a forty-dollar bill after a weekend round the bend with blood-guzzling railroad men. No plotline? No problem! As a balladeer, you’re circumscribed by narrative, history, “the facts.”

Why all this rigorous division? Because several contributors to The Rose and the Briar are cheating. Not that it matters, really. In his essay on “The Foggy, Foggy Dew,” John Rockwell notes that “until the late seventeenth century, the difference between ballad and song was slight to non-existent,” while coeditors Sean Wilentz and Greil Marcus trace the ballad to the fourteenth-century Old Provencal balada, which means simply a song “sung while dancing,” no character arc required. By the time of the American ballad, though, the form had solidified into its current definition as a narrative song, so I’m holding the editors and their charges to it.

First, the cheaters. Jon Langford of the Mekons, in an arresting collage series, turns the non sequiturs of “The Coo Coo Bird” into a ballad of sorts, a barbed situationist broadside, illustrating the decline of the USA as Slick Willie (Clinton) passed by our glazed eyes. Paul Berman offers a deep, moving tour of the mariachi orchestral tradition centered on the song “Volver, Volver,” casting the Mexican revolution and subsequent northward migration as one great ballad of a people, a nation. Luc Sante vividly evokes the prehistory of New Orleans jazz in his celebration of a freestyle rap, sometimes called “Funky Butt,” hollered from Buddy Bolden’s bandstand during a sweaty dance number. Stanley Crouch’s paean to Duke Ellington and Mahalia Jackson’s “Come Sunday,” a musical prayer, does for the civil rights movement what Berman does for the campesinos. Lastly, as much as I admire Steve Erickson’s slice of American psychogeography, Randy Newman’s “Sail Away” isn’t a ballad; rather, it’s a demonic version of what theologian Paul Tillich called a covenant—comprising a demand, a threat, and a promise.

The most profound, heartfelt pieces here address bona fide ballads, and it is no surprise that they come from female contributors—Rennie Sparks, Ann Powers, Anna Domino, Joyce Carol Oates—as many of the oldest ballads are about the violence women suffer at the hands of men. The police blotter is grim. A sample: Lady Douglas, exiled by husband for imagined infidelity; Pretty Polly, stabbed to death in woods by sweetheart; Naomi (Omie) Wise, pregnant, drowned by lover; Delia Green, fourteen, shot dead by teen boyfriend; Little Sadie, shot dead with a forty-four, no apparent reason; spurned lover of butcher boy, pregnant, suicide by hanging; wife of house carpenter, lured to sea by devil, drowned.

Women in ballads are occasionally on the right side of a gun—Frankie Baker, most famously, who shot her man Allen “Albert” Britt in 1899 St. Louis, thereby giving rise to the instant classic “Frankie and Albert”—but generally, as in real life, they are not. Men lie, break promises, and kill those who become troublesome or inconvenient, the ballads say, and it is this recurring tableau that Rennie Sparks locates at the dark heart of the ballad tradition. Writing on “Pretty Polly,” Sparks equates the fate of these wronged women with that of nature and of America itself, a land stolen from its native peoples and built on the backs of African slaves, two sins that doom the nation to cyclical rituals of persecution and bloodletting. “God will give you blood to drink!” Salem “witch” Sarah Good warned her prosecutors; “the crimes of this guilty, land: will never be purged away; but with Blood” wrote abolitionist John Brown on his way to the gallows—and both of them knew of what they spoke, being themselves victims of the paranoia, repression, and bloodlust that stalk American history like angry ghosts, giving the lie to our patriotic anthems and official self-regard.

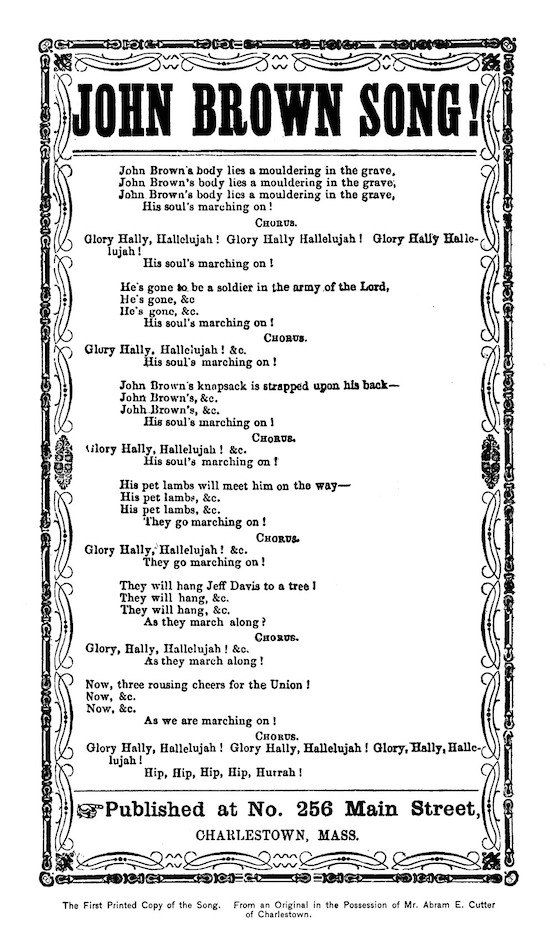

In her essay on the roots of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” Sarah Vowell reveals how the “truth” that “goes marching on” masks several less varnished truths. The song began life at John Brown’s death, as a sick joke sung by a Union Army regiment to razz their living sergeant John Brown, and once included a verse about lynching Jefferson Davis. If Julia Ward Howe’s uplifting lyric for what later became “The Battle Hymn” is America’s manifest narrative—the story we like to tell ourselves about ourselves—then its mongrel ancestor, “John Brown’s Body,” is, like most American ballads, its latent narrative, a story composed of the truths, half-truths, rumors, and myths that grow out of the bodies of the murdered, moldering in the grave. Greil Marcus writes in his “Envoi” to The Rose and the Briar that “the old ballads carried a kind of truth, or, in the art historian T.J. Clark’s phrase, a kind of collective vehemence that is its own truth.” The collective vehemence coursing through the American ballad is that of the wronged dead, and its message—reiterated by many voices, over many generations—is that truth, crushed to earth, will rise again.

Originally published in Bookforum, December-January 2005 issue.

CURATED SERIES at HILOBROW: UNBORED CANON by Josh Glenn | CARPE PHALLUM by Patrick Cates | MS. K by Heather Kasunick | HERE BE MONSTERS by Mister Reusch | DOWNTOWNE by Bradley Peterson | #FX by Michael Lewy | PINNED PANELS by Zack Smith | TANK UP by Tony Leone | OUTBOUND TO MONTEVIDEO by Mimi Lipson | TAKING LIBERTIES by Douglas Wolk | STERANKOISMS by Douglas Wolk | MARVEL vs. MUSEUM by Douglas Wolk | NEVER BEGIN TO SING by Damon Krukowski | WTC WTF by Douglas Wolk | COOLING OFF THE COMMOTION by Chenjerai Kumanyika | THAT’S GREAT MARVEL by Douglas Wolk | LAWS OF THE UNIVERSE by Chris Spurgeon | IMAGINARY FRIENDS by Alexandra Molotkow | UNFLOWN by Jacob Covey | ADEQUATED by Franklin Bruno | QUALITY JOE by Joe Alterio | CHICKEN LIT by Lisa Jane Persky | PINAKOTHEK by Luc Sante | ALL MY STARS by Joanne McNeil | BIGFOOT ISLAND by Michael Lewy | NOT OF THIS EARTH by Michael Lewy | ANIMAL MAGNETISM by Colin Dickey | KEEPERS by Steph Burt | AMERICA OBSCURA by Andrew Hultkrans | HEATHCLIFF, FOR WHY? by Brandi Brown | DAILY DRUMPF by Rick Pinchera | BEDROOM AIRPORT by “Parson Edwards” | INTO THE VOID by Charlie Jane Anders | WE REABSORB & ENLIVEN by Matthew Battles | BRAINIAC by Joshua Glenn | COMICALLY VINTAGE by Comically Vintage | BLDGBLOG by Geoff Manaugh | WINDS OF MAGIC by James Parker | MUSEUM OF FEMORIBILIA by Lynn Peril | ROBOTS + MONSTERS by Joe Alterio | MONSTOBER by Rick Pinchera | POP WITH A SHOTGUN by Devin McKinney | FEEDBACK by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FTW by John Hilgart | ANNOTATED GIF by Kerry Callen | FANCHILD by Adam McGovern | BOOKFUTURISM by James Bridle | NOMADBROW by Erik Davis | SCREEN TIME by Jacob Mikanowski | FALSE MACHINE by Patrick Stuart | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 MORE DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE (AGAIN) | ANOTHER 12 DAYS OF SIGNIFICANCE | UNBORED MANIFESTO by Joshua Glenn and Elizabeth Foy Larsen | H IS FOR HOBO by Joshua Glenn | 4CP FRIDAY by guest curators