Spoiler Alert: Pickpocket

By:

October 26, 2011

Caveat lector: may contain spoilers.

Pickpocket, dir. Robert Bresson, 1959.

He sidles up to her. A quick glance, suspicious, complicit. Does she know? Does she notice? Ostensibly they are betting on the horses. His long fingers spread, ever so slowly, over the purse. The pressure is subtle, slight, relentless. His fingertips tease the edge of the clasp. Gently, gently, yes! he pops it open. His eyes flicker. Her face is still calm, a nimbus of white against his dark intensity. The fingers slip inside the folds: one, two, three . . . we suddenly hear the horses thundering along the track. Louder, more insistent, until — he emerges with the money! The horses are unstoppable! The finish line is breached! And, it is over. The crowd disperses, he blends into the Brownian motion. He has gotten away with it! Drained by the effort, he walks/stumbles away.

And is immediately caught. End Scene One.

Pickpocket is a study not in the philosophy of a crime, but in a crime of philosophy. Why should an extraordinary man follow the rules? Why should he be yoked to the ordinary, the workaday, the petty concerns of the unexamined masses? Shouldn’t he be free?

Wouldn’t that be better for society, overall, if someone was free?

But as the detective remarks in response, what man does not consider himself to be extraordinary? If everyone acted this way, of course, society itself would collapse.

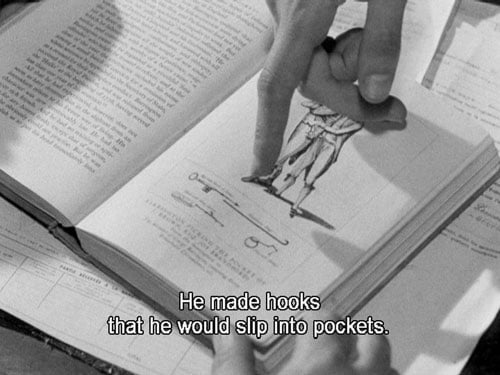

It’s not just that Michel, the pickpocket, does not want to work. He works very hard at being a pickpocket, playing pinball to increase his agility, learning teamwork with his thief buddies, practicing the different techniques for wallets, money, purses, and watches. Michel simply does not want to work at a regular job. It’s the regularity, the deadly evenness, that he despises and fears. Michel is not alone, his philosophical companions include Dostoevsky’s Raskolnikov (Crime and Punishment) and Camus’ Meursault (The Stranger). Not the happy fun guys, especially — but they do have a point.

To his point Michel sublimates all normal affections and desires. He avoids his old and ill mother, who clearly has spoiled him and believes only the best about her son. He even steals from her. He avoids Jeanne, the beautiful girl next door, who has Natalie Portman-like eyes only for him. He treats his one friend as a nuisance. Yet he actively courts the police detective, almost daring him to catch him, playing a literary cat-and-mouse game through café discourse and an exchange of books: “Am I just quoting, or am I really saying what I am saying? At what point must I be held responsible? When are we playing the language game for keeps?”

Bresson famously used non-actors in his films. He believed that actors, with their professional skills, made it too easy to manipulate the audience emotionally; that good acting, along with cinematic techniques like mood music, and the close-up, basically told us what to feel, and prevented authentic experience. Bresson is not a pickpocket, he does not want to steal your emotions. In fact, he doesn’t want them at all — he wants you to keep your emotions; he will simply tell the story.

There are many other motivations in life besides emotional attachment. Emotions are powerful, so we have a tendency to skip over all the other stuff and peak-bag the feelings. But because of their power, emotions are used to sell us; this was certainly true in the Mad Men golden era when the film takes place, but even more so now. There is no single art form, no corner of social space, no idea or fantasy or hope, that has not been repackaged as a branded affinity and sold back to us. Bresson stands aside from this trend, which necessarily implicates him in a more general economic critique, one very much on the surface in this film.

So if Pickpocket is not about emotions, what is it about? It is about daily life, about the details of going about one’s business, legal and otherwise. It is about the power of an idea, and how that can work in a very material way for good or evil in someone’s life. And it is about beauty. Beauty not only of the actors — Michel with his hooded, feline grace, and Jeanne as his proletarian Bardot — but in the chase scenes of Michel’s craft. Bresson lays out the technologies of pickpocketing almost musically, with a glissando of hands, pockets, transfers and gestures, a high/lowbrow ballet of currency and craft.

Michel increases his activities, and the police increase theirs. Both are racing towards an asymptotic apotheosis — it seems Michel must be caught; and yet there will always be more pickpockets to pick up where he left off.

But this is not Sartre’s No Exit. Bresson finally reveals an introjected expression of freedom — yes, there is no one of us that does not consider him- or herself extraordinary. And yet, it is available to all of us to express our real exceptionalism. The way out is not to cross the social commons, or to violate the common law. Freedom is ineffable and everywhere, as is grace, as is love; we simply have to recognize it. But of course, there’s nothing simple about that recognition. Bresson was Catholic and his films can be glimpsed through that veil. But it is the mark of a masterpiece that it is open to many readings.

The unexpected final scene and true climax of the film, in which very solid barriers become vulnerable to a more fluid transgression, is a climax for the audience as well. Because when emotion is finally allowed back into Bressonian space, as it must be, it does not belong to the film. It belongs to you.

A version of this essay appeared on the Brattle Theater Film Blog, June 2009.

Read more Spoiler Alerts.