Exquisite Corpus

By:

April 13, 2011

Towards the end of Wim Wenders’ Until the End of the World, the late, great Solveig Dommartin suffers from “image addiction.” She has left Sam Neill, a writer, for William Hurt, who is on the run for industrial espionage. He has invented a pair of glasses that hook right into the optic nerves, allowing the blind to see recordings, and has stolen back his own invention from the CIA, intending to give it to his blind mother. However, a few further tweaks and the glasses begin to record dreams, and it is to the playback of these images that Dommartin’s character becomes addicted. Sleeping through the unremembered movies of her mind (as most of us do), she wakes to scan the recordings in the morning — and soon does nothing else. The gestures and resonant ambiguities of dream-fragments seem to indicate a further, elusive meaning: perhaps Meaning Itself, perhaps just the meaning of her own life, which of course is endlessly fascinating to that life’s inhabitant. Moving beyond language, unwilling to pin the various butterflies of thought, not only will she not describe the narrative fragments, she soon doesn’t even look beyond the internalized lens.

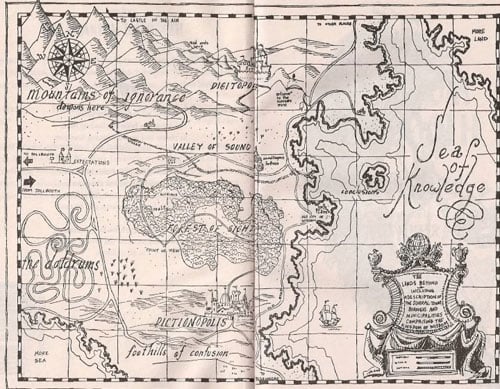

At this point it is language to the rescue, in the form of her writer-ex, who confiscates the glasses and pens her in a large-mammal-style chainlinked enclosure, where she gestures desperately through the gaps to have the glasses returned. Eventually, the addiction is broken. Words and time have un-made the vague imagistic signposts and un-marked the path, which promised the Grail but may have led only to the Doldrums, where plaid Lethargians wait to cling to socks.

[Jules Feiffer, illustrations for the Phantom Tollbooth, written by Norton Juster]

The other day on Twitter, a new site popped up and swept through at least my corner of the Twitterverse. Called That Can Be My Next Tweet, it grabs your recent tweets and scrambles them in a subject-object kind of way, preserving just enough of the fragment so that it makes a kind of sense, even when combined with similar fragments from other thoughts. Then with one click you can retweet the results. Of course some scrambles were just scrambled. But, compellingly, these unrelated fragments are related just enough (through the filter of your own mind, and your own written rendition of such) to seem to indicate something closer to Meaning, or at least the meaning of your own life (or its construction, which in language is the same thing).

And tellingly the meaning of your own life was the most fascinating. You can type in anyone’s Twitter handle and see your friends’ scrambles, but the most compelling mashups are your own. What are you saying? What are you saying behind the sayings? What is trying to break free, to hatch, to channel through you into being and awareness?

Earthbound Ian Anderson to hum while u don’t tell me of mist, slowly revealing her skirts of mist, slowly.

Christian bale could *totally play the necessity of incomprehension, plenty of fugitive sheets as.

Polyhedra have their fine points! as it vibrates as acknowledgement. but I don’t tell me in answer to!

hipsters at the Spectacle featuring Alan Turing, Pontius Pilate, Henry.

the transparent taxonomies of molly bloom’s dialogue!

It was addicting, and I was completely sucked in. But only for about a half-hour; it didn’t go far enough. The app only mines the most recent tweets, and repetitions in the phraseology come up fairly quickly. When you can see the algorithm at work you are reminded that the man behind the curtain is you.

Quantity is key for algorithmic epiphanies. The angels of information thrive in numbers: in order to divine mysteries, we must first get them out of our sight. Hiding in the crowd will do it.

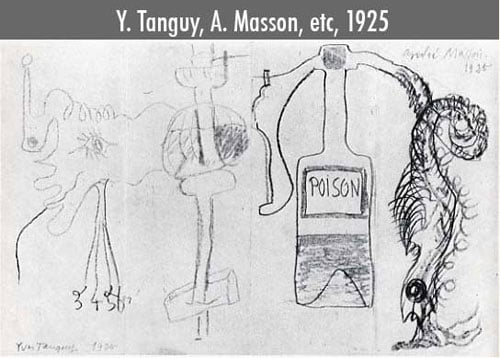

[an Exquisite Corpse, Y. Tanguy and A. Masson, 1925]

Maybe this kind of tech, whether pursued with paper and pictures, or text and keyboards, leads nowhere. Maybe it’s just a surrealistic game, a few minutes’ or hours’ time spent with randomness, possibly worth tweeting about. But the best surrealistic games were not games. Which is to say, yes they were, but they used randomness and absurdity to short-circuit the rational mind and its perceptual architectures, drifting instead along a psychogeography of the soul that might lead anywhere, perhaps even to significance.

Or just to the next whisky bar. But who is to deny the Grails that may indeed reside therein?