To Err is Divine

By:

January 21, 2010

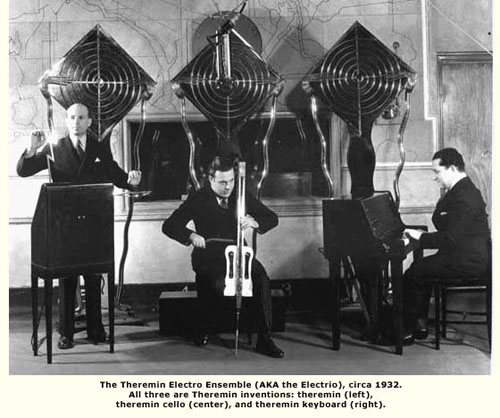

The theremin is a perfect instrument: it plays all the notes. Not only those we discretely declare, but every tone in between. Such a surfeit anchors it firmly in the uncanny valley — too much is as strange as too little. Which is why it was so easily assigned to B-movie aliens. And Brain Wilson. We’re used to gaps, and steps, as we stutter and leap along our infinite incompleteness.

It does not of course play every sound, just every point along a certain vector, within a set of related vectors controlled by the brightness and waveform dials. Together these describe a dense orange segment, one so sweet with information we can hardly bear it. In fact, sliding up and down the soundlines so saturates the ear that it surrenders, and the horizon is lost, adrift in a plateau of microtones. Soundblindness.

So a robot should be perfect, right? As only one machine can be for another. It’s all mathematics: simply calculate the frequency and program the moves. Here’s “Lev,” with his interpretation of Crazy:

[Lev playing Crazy by Patsy Cline]

Yeah.

But it’s hitting the notes, right? Yes, it is hitting the notes, right. But within its perfection lies a sin of omission — what’s missing is the error.

Or as it’s sometimes called, vibrato. What is vibrato but wiggling around in the general vicinity so that your note ends up with the highest probability rating? And the other notes do not detract; no, somehow they augment, heightening the sweetness with just the right amount of pith. Here’s Clara Rockmore introducing noise into the signal:

[Clara Rockmore playing Le cygne from Le carnaval des animaux by Camille Saint-Saëns (composed 1886)]

Her technique is no accident. Compare Rockmore’s theremusicality to that of a coloratura soprano:

[Maria Callas singing O mio babbino caro from the opera Gianni Schicchi by Giacomo Puccini (composed 1918)]

Happily for our mashup era there’s plenty of crossover in alt-mechanickal aetherics. Here’s possibly the most famous of them all, wherein a voice imitates a theremin for a B-movie TV show frequently involving aliens:

[Theme from Star Trek by Alexander Courage, second season remix featuring Loulie Jean Norman (composed 1966)]

Why settle for perfection?