Igor’s Blues

By:

June 10, 2009

WHEN I WATCH old monster movies, I think, What is it with these scientists? Whenever you have some Misshapen Fiend lurching all over the frame, muttering gibberish, trying to kill everything in its path and generally acting like a junkyard dog, odds are there’s a Scientist — lab coat, beakers, and all — who’s the cause of the problem.

Why are these scientists involved with monsters instead of, like, collecting graduate students, filling out requisitions for more petri dishes, arguing with their colleagues about tenure, and other properly scientific stuff?

Glad you asked. And thanks for stopping by. You wouldn’t want to leave just yet; it is, after all, a dark and stormy night. You like ghost stories, don’t you? Sit right down, let’s start with you.

Tell me all about yourself — and these friends of yours, too. How well do you know them? I mean, you hear their words, and observe their actions, and draw certain conclusions, right? But you can’t read their minds. Perhaps you sometimes wonder: How far does it go? How much is everyone concealing? Who are these people I think I know? For that matter, how well do you know yourself? You sometimes say things you don’t mean. And there are a few things you do that you don’t want anyone else to know about. Right?

That’s what I thought.

Monster movies play on exactly this kind of epistemological dread: how do we know what we know? As of the latest reports, we still really can’t say. We can say what we believe, and what we think we know, and what others insist upon, but we don’t have ultimate proof of the kind that would finally allay our fears and allow us to plant our feet firmly upon the ground and kick rocks, philosophically speaking. Science is the practice that’s supposed to provide such proof for us, tell us what the world (and the mind) is really like, “illuminate the subject with a great white light, to the inexpressible advancement of human knowledge,” to borrow a phrase from Ambrose Bierce’s definition of magnetism.

Scientists are supposed to reveal the structure of reality so the rest of us don’t have to worry about it and can get on with whatever it is that we think we’re doing, like driving around in our cars and renting videos and going to work and talking on the phone. Quick: what’s the ultimate, indivisible unit of matter? An atom? An electron? A quark? A psion? An antimatter particle? Or is everything just a cloud of probability states with different ways of manifesting in the world depending on whether or not the thing thinks I’m looking at it?

The thing thinks I’m looking at it? This is supposed to be reassuring?

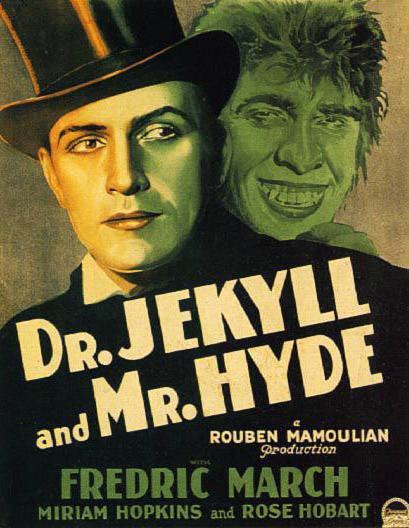

In short, worries persist. We want the scientist to be Dr. Jekyll, discovering and explaining the foundations of reality. Instead, he’s Mr. Hyde — he’s cloning sheep, growing square tomatoes, perfecting Agent Orange, and putting Thorazine in the water supply. Remember in Scooby Doo, how the culprit so often turned out to be Dr. Wilson from the lab? We’ve displaced our fear that reality itself is chaotic and flexible instead of ordered and stable onto the figure of the scientist. Like the reality we long for him to explain, the scientist in the popular imagination isn’t what he seems. So what is the scientist? In popular culture, we’re always afraid the answer is going to be: Monster, run for your lives!

How to deal with the monstrous realization that reality is not what we imagine it to be? Not through conventional means. You know how the police and the military are always called in to stop the monsters, but their bullets and missiles have no effect? Conventional law enforcement and military actions are only effective under the laws of conventional reality. Once those laws have been repealed: Your bullets are useless against me, mortals! Ah ha ha!

Monster-movie scientists with their bubbling beakers are updated versions of witches and druids with bubbling cauldrons — earlier figures, that is to say, onto whom the rest of us displaced our anxiety about the reality of reality. This anxiety has a long historical precedent: Gnostic movements dating back to the third century after Christ claimed that humans are divine souls trapped in a material reality (created by an imperfect god, the Demiurge) that is not merely an inferior simulacrum of a higher-level reality, but an evil prison for its deluded inhabitants. Scientists, in 20th-century pop culture, were charged with the task of (a) figuring out the truth about reality, and (b) rescuing us from this invisible prison. But inevitably, they failed at both.

The scientist’s work of analyzing reality as we perceive it seems to makes no sense. Everyone can see that the sun revolves the Earth, so why investigate this fact? Starting with the discovery that the Earth revolves around the sun, scientific investigations have made us more, not less anxious, about the realness of reality. We are made up of mostly empty space! There are black holes that warp the fabric of space-time! Space-time is a fabric? Our monsters — the Other to our Same — reflect our ever-increasing horror about reality itself: giant bugs and animals that want to destroy our cities, tiny bugs and animals that want to destroy our cities, aliens that invade from outer space, aliens that invade from the inside out, not to mention legions of undead zombies who are getting faster all the time.

Fear of the Other may be epistemological in origin, but it has very real social and political consequences. Who are those people who look and act differently? How can we believe anything they say — including, “We come in peace?” Since we can’t really know anyone, might not everyone we know be Other? In that case, might not everyone we know be a… Monster, run for your lives!

And what about you? Why do monsters want to kill you? Why should you care if they do kill you; what’s so important about living? What’s the meaning of life — yours, or generally speaking? Are you sure? How do you know? You don’t, really — and that’s terrifying, too. Meaninglessness is aggressive and unstoppable, and you’re its target. As Jean-Paul Sartre might say, meaninglessness itself is a… Monster, run for your lives!