OFF-TOPIC (7)

By:

July 20, 2019

Off-Topic brings you over-the-transom, on-tangent essays, dialogues and subjective scholarship on an occasional, impulsive basis. This month, some revelations from a behind-the-scenes wizard of sound on what the record doesn’t show.

You’re not Martin Mills, and neither is he. An American Sociopath at home in the 1980s music business and hiding a previous career as an unspecified assassin, Mills makes millions by spotting the rarest talent and richest target audiences while moving unnoticed in the Dayglo Decade’s garish habitat, one of many creating obscene wealth undercover in the golden age of surface.

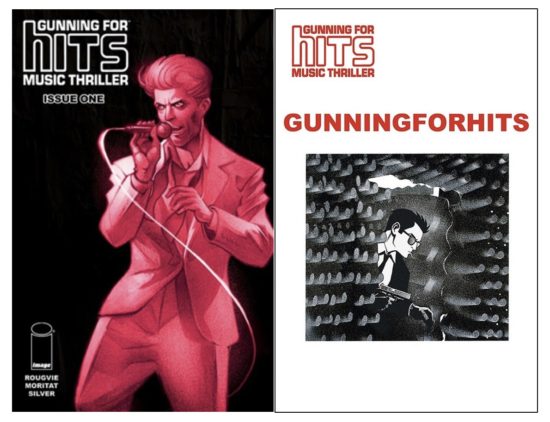

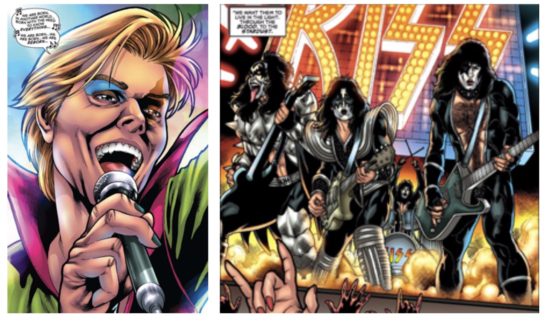

He’s nothing like his kindly twin Jeff Rougvie, indie record-exec and natural storyteller, who has a genie’s-bottle-full of industry legends he’s sealed Martin safely into, starting with the runaway-success debut comic, Gunning for Hits (from Image). Entertainment and criminality have been in a duet for as far back as either goes, and GfH is like Rougvie’s doppelganger diary of a crass and cutthroat culture in contrast to the career of inspiration and integrity he’s actually had… though truth and fiction have been dancing around each other and making beautiful music for millennia too.

The series’ first arc (premiering in collected form at San Diego Comic Con around the time you read this) holds a funhouse filter to Rougvie’s real-life years as a new hire handed the repackaging of David Bowie’s catalog (and rehabilitation of his career) at the Ryko label as the ’90s loomed; in GfH the prematurely grizzled Mills tries to resuscitate his hero “Brian Slade” while cultivating the next craze and fighting off his own extinction in the corporate ecology. (Slade is of course yet another layer of tear-away personality, sharing a name but traveling a separate timeline from the Bowie-analog in Velvet Goldmine .)

Cartoonist Moritat expresses the absurdities and intensities of this lost, recent world with a multi-octave visual voice, and Rougvie’s own ear is unerring for natural speech, period detail, psychological truth and wild wit, all plotted as tensely as the best of crime-lit and wound tightly as the sharpest clockwork farce. Rougvie and I got together to talk optional identities, revisionist reality and inescapable pasts.

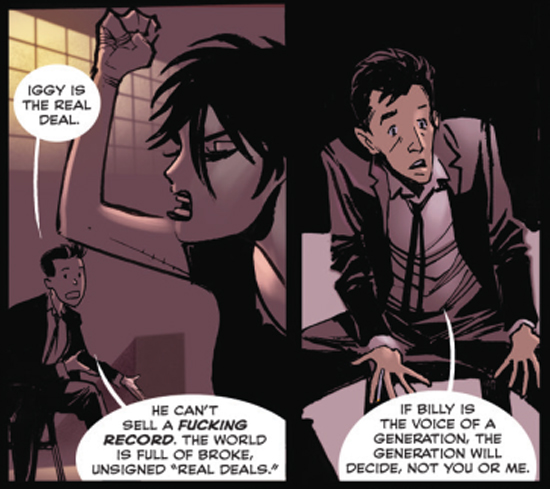

HILOBROW: One of the main things that fascinated me about your comic is how it seemed to follow the roads-not-taken, albeit through times that we definitely recognize and remember. The Brian Slade character, for one thing, is almost this shadow biography of all the worst rumors and negative impressions that people had of Bowie. Did you make that decision to kind of tell the story of all the people that you and your associates were not?

ROUGVIE: Bowie got to [a] point in the ’80s where he could’ve said, “Y’know, who cares? I’m selling millions of records and getting huge advances from EMI. I’ll just keep making these,” what he called his “Phil Collins records” [laughter]. And instead he put together Tin Machine, which was a great way to challenge himself artistically, but got him dropped from the label, and put him in a very difficult position for five or six years.

I started working with him [in] 1989, right before the Tin Machine record came out. As a small company, we had invested a ton of money in his back catalog. We never had any doubt he’d regain his stature, so to speak, and his back catalog would continue to be popular. But there was a brief minute where it did cross my mind, what if he kept making records that didn’t connect and ended up playing state fairs in 1999? You never know. Luckily for us he made all the right choices. So the idea [for GfH] was, what if he hadn’t been such a genuine artist, but somebody who didn’t have [as much] integrity or drive?

HILOBROW: You’re probably too modest to answer, but how much of a role did the Sound + Vision project have in restoring his confidence?

ROUGVIE: It forced him to reassess his back catalog, and helped him appreciate how great those records were and where they were going to fit into his overall legacy. Also the pretense of the Sound + Vision tour was that he was no longer going to play any of his best-known songs live, ever again. When you’re letting go of almost all your hits, you’ve forced yourself into a corner and the only option is to fight your way out. The reception to the Sound + Vision campaign helped reestablish him as an artist at the right time in the minds of a lot of the public, and it introduced him to new generations, but the challenges he gave himself subsequently really made the difference in his career going forward.

HILOBROW: I guess Sound + Vision was the ground-zero of a pattern where, whenever he had something new out, there would be a retrospective project too, for the rest of his career.

ROUGVIE: As he got older, he was thinking a lot about his mortality, what his legacy was going to be and how to frame it. You look at a lot of rockstars’ careers, and the legacy is not well-curated; his is very well-curated. It helps that there are all these different Bowies that are entry points for people. That’s the ultimate genius of the whole thing. That’s one of the reasons why I like the idea of using the Brian Slade character; I think now that Bowie’s gone, he would like us to create more Bowies.

HILOBROW: In many ways, Martin Mills seems to be playing more of a role than any of Slade’s passing personas. Could anyone pass themself off as someone they’re not (or I guess, an extra person that they are) quite that way in the era of omnipresent self-surveilling social media? Is he an artifact of a time when that kind of secrecy was possible? Or is he just one of the many heirs of Bowie-esque self-invention?

ROUGVIE: It’s a bit of both. Martin’s figuratively living off the grid, but in this fairly glamorous world. He’s partly doing that himself, but there’s some outside assistance we haven’t met yet that keeps him from having to deal with the remnants of his past. On the other hand, when I wrote this, I was thinking about how Bowie just blended into New York, even into this century when there were cameras everywhere. I love that about New York; people really don’t care. And Martin is not a person who’s ever sought celebrity… later on in the series, there is a point where he becomes very well-known, and it’s a problem for him and other people [laughter]. But unless you’re on the cover of a magazine, or movies or TV — or even if you are — most of the time nobody cares… I breezed past Gwyneth Paltrow and Chris from Coldplay just walking in Union Square and nobody was bothering them, they were just out eating ice cream.

HILOBROW: It’s like one big stage set.

ROUGVIE: The New York thing is, “we’re all in it together” — you treat people the way you want to be treated or it goes sideways fast in New York.

HILOBROW: [Laughs] Speaking of Martin’s story, I’m curious about his “journal entries” on Twitter (@MartinMillsHits); do you excerpt them from lengthier texts you have, or are you just composing the narrative from these fragments as you go along?

ROUGVIE: I’d had this story in mind for a long time, and the Martin character came along later. When I sat down to write this arc, I ended up writing his whole life story. It’s not as fleshed out as [the comic], but I know what happens and when.

HILOBROW: You’ve said that one of your own roads-not-taken (’til now) was making comics; did an interest in visual narrative connect your love of comics with love of an artist like Bowie who was so much about the visual?

ROUGVIE: Yeah, very much. When I first started getting into music as a teenager, if you saw the cover of Destroyer and were reading comics, you just bought that record. My feeling is, of course, you can make great music in jeans and a leather jacket. Music doesn’t require you to be very image-conscious; Tom Petty’s a perfect example of that. By the same token, if you’re going out on stage and giving people a show, do something big, if you can, or have ideas that are more than that. It is “show business” after all, and that visual stuff does really put it over for me. KISS records are not particularly masterful, but there’s just something great about the big dumb spectacle of it all that, to me, sells the whole package. And if Gene Simmons would stop doing interviews I probably would still be a huge KISS fan! [laughter] But I do think that that’s part of it, and — unless you go too far, I don’t think anybody’s ever been ruined by refining their visual image. I would much rather go to a Janelle Monáe show than, I dunno, see Miscellaneous Guy-With-Beard.

HILOBROW: I loved what you wrote in the regular comic’s backmatter about how you said to Moritat, “It’s set in the ’80s but it shouldn’t all look like a Nagle drawing.” Comics that are true to their period are rare, but GfH does feel that way, without being just, like, a fossil of big hair and shoulderpads set in amber. I know it started brewing in your mind at the end of the ’80s, and you’ve been kind of adding to the past as you developed the story. What are your thoughts on keeping it believable to its period, yet feeling as immediate as it does?

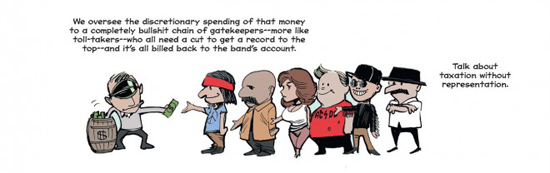

ROUGVIE: I think if the story works, the period you choose to put it in can either enhance or detract. If you look at the Gunning for Hits logo, it’s based on the Compact Disc logo. And that’s important, because during the CD era, the business was really changing. The label guys who were real maverick lunatics that started labels and either got lucky or were good at picking artists were imperiled. These people wouldn’t sink loads and loads of money into records, but they would keep an artist’s career going. Nearly all those guys get bumped out during the ’80s, because the big corporations are realizing, hey, they own all these recordings, and people will buy them again on CD, so we, the big corporations, are going to come in and buy up all these labels, because it’s boom time. That’s a bad turning point in the history of the music business; and New York is also undergoing this crazy gentrification, where the artists are getting forced out of Soho. That world that spawned punk and downtown artists is changing forever. In a broad sense, one of the things, amongst many, that Gunning for Hits is about, is the balance of art and commerce, and how does that work. The ’80s were a time when that balance was really under fire. So I’m using the series to explore that, but I definitely didn’t want to dress it up in all of the clichés of the ’80s.

HILOBROW: Talking about the crossroads of art and commerce in the ’80s is interesting, since one thing that struck me about some of the dates for entries in Martin’s journal on Twitter is that he somehow survived longer than the record industry as we knew it.

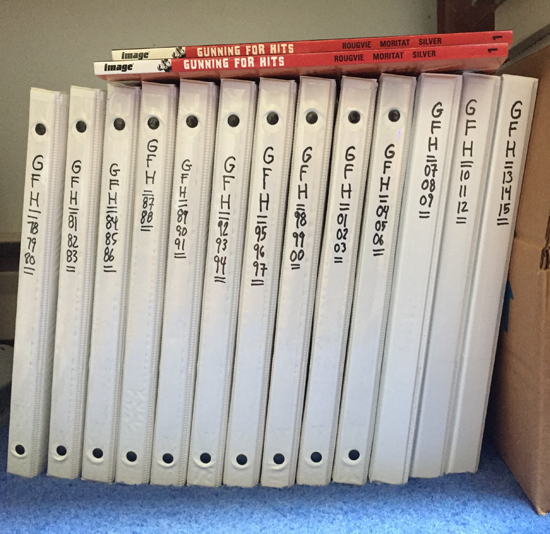

ROUGVIE: He did, even if a handful of people would argue the music business is thriving, although I disagree. I haven’t decided when I’m going to jump around time-wise; the next storyline does take place right after this one. But there are things to tell about Martin’s past that we’ll need to get to before we can get up to the present… and I think I’ve said this before, but he’s dead now; in 2019 he’s dead. So there’s a definite end. And there’s a specific incident where he’s finally had enough with the music business, and that is one of the best story ideas I’ve ever had, if I do say so myself. I’d guess I have about a hundred Martin Mills stories. I printed out calendars for every year that has significant events in his life, and annotated the dates where things happen. So I’ve got about 15 binders full of calendars with Martin’s story in them.

HILOBROW: Binders full of Martin, I can’t wait to see everything that’s in the vault!

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2024 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE