THE TISSUE-CULTURE KING (8)

By:

October 22, 2022

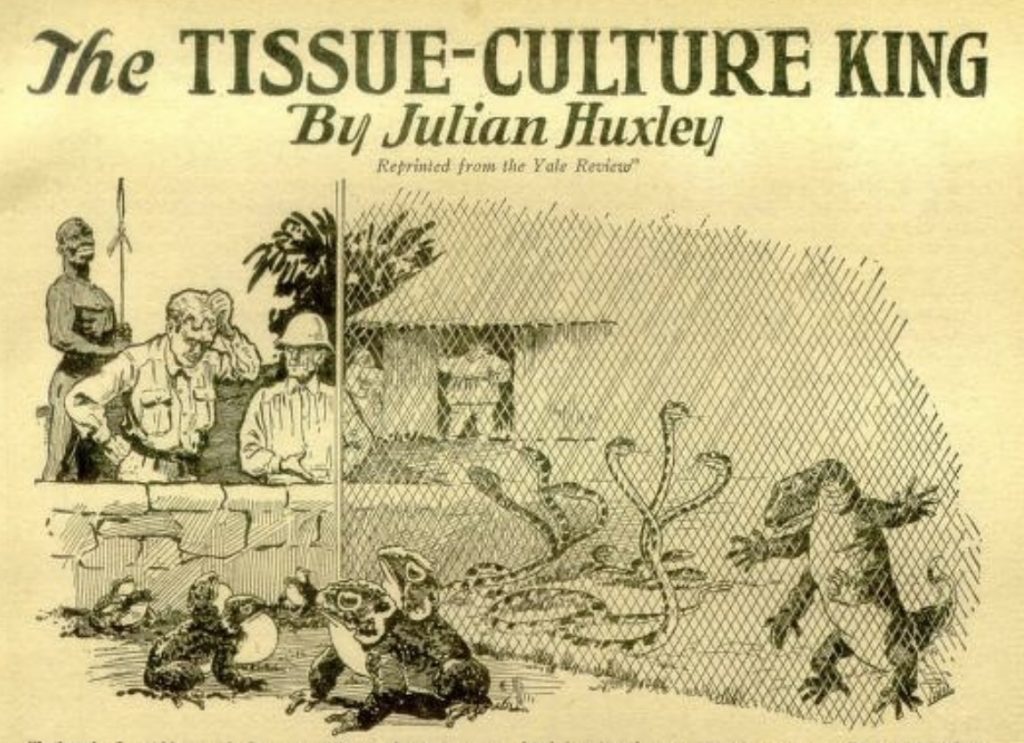

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize “The Tissue-Culture King,” a 1926 short story by biologist Julian Huxley, for HILOBROW’s readers. Sometimes subtitled “A Parable of Modern Science,” it is an allegory of science’s subordination to capitalist imperatives. Fun fact: Here is where you will find one of the earliest mentions of the anti-telepathic properties of tin-foil hats.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9.

Bugala was deeply interested. He saw himself, through this mental machinery, planting such ideas as he wished in the brain cases of his people. He saw himself willing an order; and the whole population rousing itself out of trance to execute it. He dreamt dreams before which those of the proprietor of a newspaper syndicate, even those of a director of propaganda in wartime, would be pale and timid. Naturally, he wished to receive personal instruction in the methods himself; and, equally naturally, we could not refuse him, though I must say that I often felt a little uneasy as to what he might choose to do if he ever decided to override Hascombe and to start experimenting on his own. This, combined with my constant longing to get away from the place, led me to cast about again for means of escape. Then it occurred to me that this very method about which I had such gloomy presentiments, might itself be made the key to our prison.

So one day, after getting Hascombe worked up about the loss to humanity it would be to let this great discovery die with him in Africa, I set to in earnest. “My dear Hascombe,” I said, “you must get home out of this. What is there to prevent you saying to Bugala that your experiments are nearly crowned with success, but that for certain tests you must have a much greater number of subjects at your disposal? You can then get a battery of two hundred men, and after you have tuned them, the reinforcement will be so great that you will have at your disposal a mental force big enough to affect the whole population. Then, of course, one fine day we should raise the potential of our mind-battery to the highest possible level, and send out through it a general hypnotic influence. The whole country, men, women and children, would sink into stupor. Next we should give our experimental squad the suggestion to broadcast ‘sleep for a week.’ The telepathic message would be relayed to each of the thousands of minds waiting receptively for it, and would take root in them, until the whole nation became a single superconsciousness, conscious only of the one thought ‘sleep’ which we had thrown into it.”

The reader will perhaps ask how we ourselves expected to escape from the clutches of the superconsciousness we had created. Well, we had discovered that metal was relatively impervious to the telepathic effect, and had prepared for ourselves a sort of tin pulpit, behind which we could stand while conducting experiments. This, combined with caps of metal foil, enormously reduced the effects on ourselves. We had not informed Bugala of this property of metal.

Hascombe was silent. At length he spoke. “I like the idea,” he said; “I like to think that if I ever do get back to England and to scientific recognition, my discovery will have given me the means of escape.”

From that moment we worked assiduously to perfect our method and our plans. After about five months everything seemed propitious. We had provisions packed away, and compasses. I had been allowed to keep my rifle, on promise that I would never discharge it. We had made friends with some of the men who went trading to the coast, and had got from them all the information we could about the route, without arousing their suspicions.

At last, the night arrived. We assembled our men as if for an ordinary practice, and after hypnosis had been induced, started to tune them. At this moment Bugala came in, unannounced. This was what we had been afraid of; but there had been no means of preventing it. “What shall we do?” I whispered to Hascombe, in English. “Go right ahead and be damned to it,” was his answer; “we can put him to sleep with the rest.”

So we welcomed him, and gave him a seat as near as possible to the tightly packed ranks of the performers. At length the preparations were finished. Hascombe went into the pulpit and said, “Attention to the words which are to be suggested.” There was a slight stiffening of the bodies. “Sleep,” said Hascombe. “Sleep is the command: command all in this land to sleep unbrokenly.” Bugala leapt up with an exclamation; but the induction had already begun.

We with our metal coverings were immune. But Bugala was struck by the full force of the mental current. He sank back on his chair, helpless. For a few minutes his extraordinary will resisted the suggestion. Although he could not move, his angry eyes were open. But at length he succumbed, and he too slept.

We lost no time in starting, and made good progress through the silent country. The people were sitting about like wax figures. Women sat asleep by their milk-pails, the cow by this time far away. Fat-bellied naked children slept at their games. The houses were full of sleepers sleeping upright round their food, recalling Wordsworth’s famous “party in a parlor.”

So we went on, feeling pretty queer and scarcely believing in this morphic state into which we had plunged a nation. Finally the frontier was reached, where with extreme elation, we passed an immobile and gigantic frontier guard. A few miles further we had a good solid meal, and a doze. Our kit was rather heavy, and we decided to jettison some superfluous weight, in the shape of some food, specimens, and our metal headgear, or mind-protectors, which at this distance, and with the hypnosis wearing a little thin, were, we thought, no longer necessary.

About nightfall on the third day, Hascombe suddenly stopped and turned his head.

“What’s the matter?” I said. “Have you seen a lion?” His reply was completely unexpected. “No. I was just wondering whether really I ought not to go back again.”

“Go back again,” I cried. “What in the name of God Almighty do you want to do that for?”

“It suddenly struck me that I ought to,” he said, “about five minutes ago. And really, when one comes to think of it, I don’t suppose I shall ever get such a chance at research again. What’s more, this is a dangerous journey to the coast, and I don’t expect we shall get through alive.”

I was thoroughly upset and put out, and told him so. And suddenly, for a few moments, I felt I must go back too. It was like that old friend of our boyhood, the voice of conscience.

“Yes, to be sure, we ought to go back,” I thought with fervor. But suddenly checking myself as the thought came under the play of reason — “Why should we go back?” All sorts of reasons were proffered, as it were, by unseen hands reaching up out of the hidden parts of me.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.