THE TISSUE-CULTURE KING (2)

By:

September 11, 2022

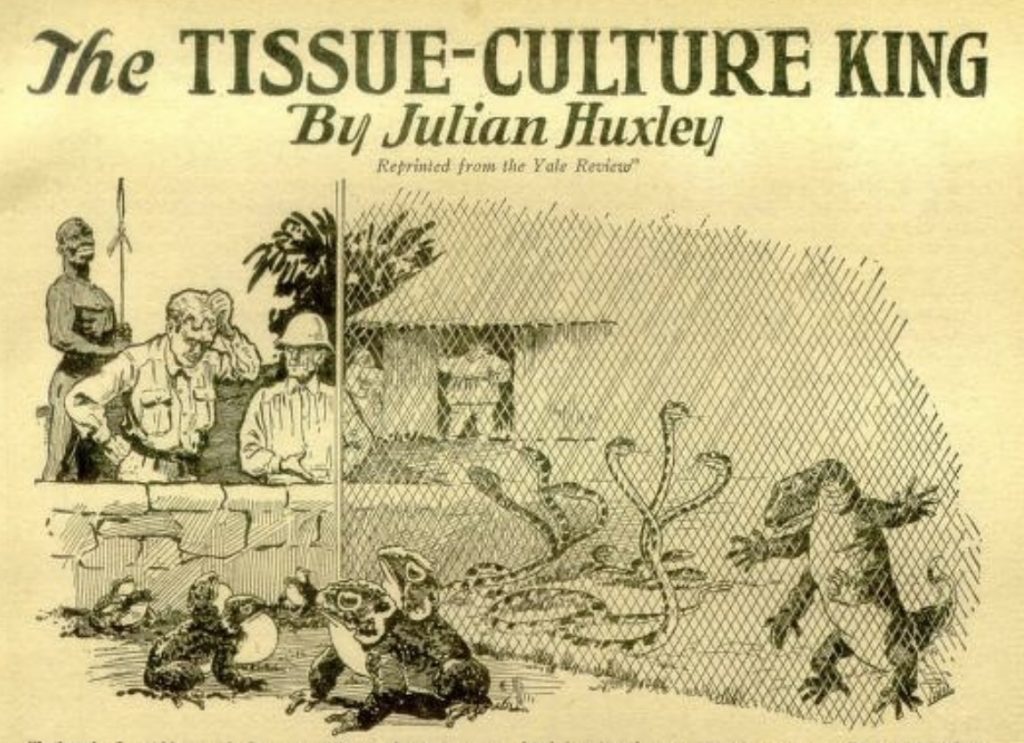

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize “The Tissue-Culture King,” a 1926 short story by biologist Julian Huxley, for HILOBROW’s readers. Sometimes subtitled “A Parable of Modern Science,” it is an allegory of science’s subordination to capitalist imperatives. Fun fact: Here is where you will find one of the earliest mentions of the anti-telepathic properties of tin-foil hats.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9.

But another surprise was in store for me. I saw a figure pass across from one large building to another — a figure unmistakably that of a white man. In the first place, it was wearing white ducks and sun helmet; in the second, it had a pale face.

He turned at the sound of our cavalcade and stood looking a moment; then walked towards us.

“Halloa!” I shouted. “Do you speak English?”

“Yes,” he answered, “but keep quiet a moment,” and began talking quickly to our leaders, who treated him with the greatest deference. He dropped back to me and spoke rapidly: “You are to be taken into the council hall to be examined; but I will see to it that no harm comes to you. This is a forbidden land to strangers, and you must be prepared to be held up for a time. You will be sent down to see me in the temple buildings as soon as the formalities are over, and I’ll explain things. They want a bit of explaining,” he added with a dry laugh. “By the way, my name is Hascombe, lately research worker at Middlesex Hospital, now religious adviser to His Majesty King Mgobe.” He laughed again and pushed ahead. He was an interesting figure — perhaps fifty years old, spare body, thin face, with a small beard, and rather sunken, hazel eyes. As for his expression, he looked cynical, but also as if he were interested in life.

By this time we were at the entrance to the hall. Our giants formed up outside, with my men behind them, and only I and the leader passed in. The examination was purely formal, and remarkable chiefly for the ritual and solemnity which characterized all the actions of the couple of dozen fine-looking men in long robes who were our examiners. My men were herded off to some compound. I was escorted down to a little hut, furnished with some attempt at European style, where I found Hascombe.

As soon as we were alone I was after him with my questions. “Now you can tell me. Where are we? What is the meaning of all this circus business and this menagerie of monstrosities? And how do you come here?” He cut me short. “It’s a long story, so let me save time by telling it my own way.”

I am not going to tell it as he told it; but will try to give a more connected account, the result of many later talks with him, and of my own observations.

Hascombe had been a medical student of great promise; and after his degree had launched out into research. He had first started on parasitic protozoa, but had given that up in favor of tissue culture; from these he had gone off to cancer research, and from that to a study of developmental physiology. Later a big Commission on sleeping sickness had been organized, and Hascombe, restless and eager for travel, had pulled wires and got himself appointed as one of the scientific staff sent to Africa. He was much impressed with the view that wild game acted as a reservoir for the Trypanosoma gambiense. When he learned of the extensive migrations of game, he saw here an important possible means of spreading the disease and asked leave to go up country to investigate the whole problem. When the Commission as a whole had finished its work, he was allowed to stay in Africa with one other white man and a company of porters to see what he could discover. His white companion was a laboratory technician, a taciturn noncommissioned officer of science called Aggers.

There is no object in telling of their experiences here. Suffice it that they lost their way and fell into the hands of this same tribe. That was fifteen years ago; and Aggers was now long dead — as the result of a wound inflicted when he was caught, after a couple of years, trying to escape.

On their capture, they too had been examined in the council chamber, and Hascombe (who had interested himself in a dilettante way in anthropology as in most other subjects of scientific inquiry) was much impressed by what he described as the exceedingly religious atmosphere. Everything was done with an elaboration of ceremony; the chief seemed more priest than King, and performed various rites at intervals, and priests were busy at some sort of altar the whole time. Among other things, he noticed that one of their rites was connected with blood. First the chief and then the councillors were in turn requisitioned for a drop of vital fluid pricked from their finger tips, and the mixture, held in a little vessel, was slowly evaporated over a flame.

Some of Hascombe’s men spoke a dialect not unlike that of their captors, and one was acting as interpreter. Things did not look too favorable. The country was a “holy place,” it seemed, and the tribe a “holy race.” Other Africans who trespassed there, if not killed, were enslaved, but for the most part they let well alone, and did not trespass. White men they had heard of, but never seen till now, and the debate was what to do — to kill, let go, or enslave? To let them go was contrary to all their principles: the holy place would be defiled if the news of it were spread abroad. To enslave them — yes; but what were they good for? and the Council seemed to feel an instinctive dislike for these other-colored creatures. Hascombe had an idea. He turned to the interpreter. “Say this: ‘You revere the Blood. So do we white men; but we do more — we can render visible the blood’s hidden nature and reality, and with permission I will show this great magic.'” He beckoned to the bearer who carried his precious microscope, set it up, drew a drop of blood from the tip of his finger with his knife and mounted it on a slide under a coverslip. The bigwigs were obviously interested. They whispered to each other. At length, “Show us,” commanded the chief.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.