THE TISSUE-CULTURE KING (6)

By:

October 10, 2022

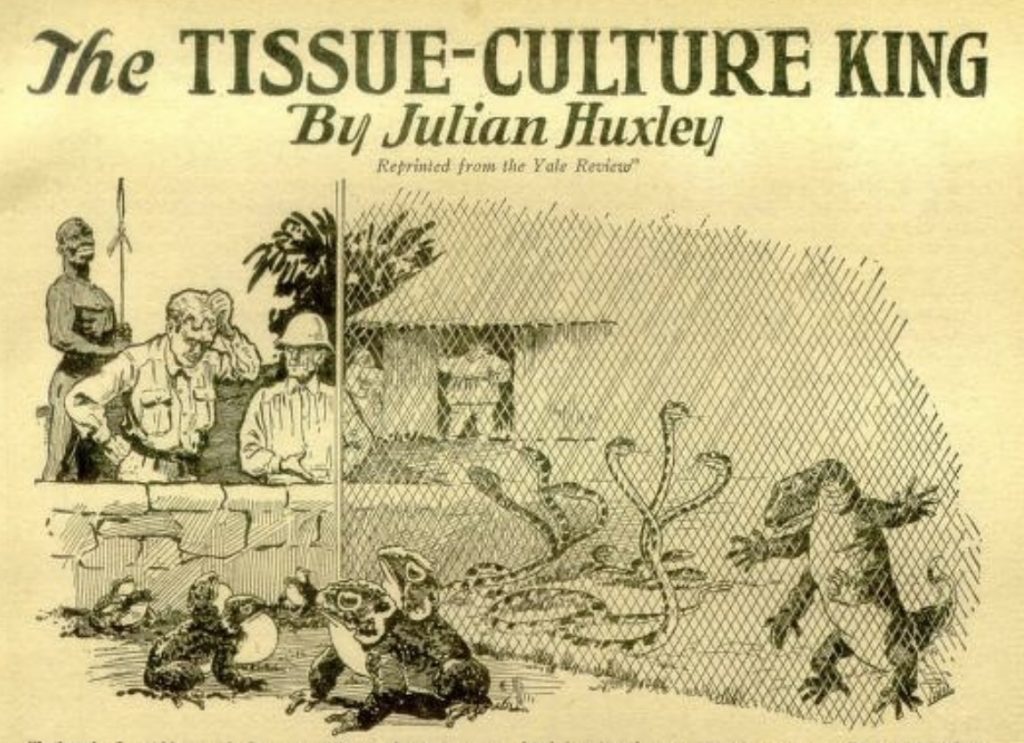

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize “The Tissue-Culture King,” a 1926 short story by biologist Julian Huxley, for HILOBROW’s readers. Sometimes subtitled “A Parable of Modern Science,” it is an allegory of science’s subordination to capitalist imperatives. Fun fact: Here is where you will find one of the earliest mentions of the anti-telepathic properties of tin-foil hats.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9.

The second building was devoted to endocrine products — an African Armour’s — and was called by the people the “Factory of Ministers to the Shrines.”

“Here,” he said, “you will not find much new. You know the craze for ‘glands’ that was going on at home years ago, and its results, in the shape of pluriglandular preparations, a new genre of patent medicines, and a popular literature that threatened to outdo the Freudians, and explain human beings entirely on the basis of glandular make-up, without reference to the mind at all.

“I had only to apply my knowledge in a comparatively simple manner. The first thing was to show Bugala how, by repeated injections of pre-pituitary, I could make an ordinary baby grow up into a giant. This pleased him, and he introduced the idea of a sacred bodyguard, all of really gigantic stature, quite overshadowing Frederick’s Grenadiers.

“I did, however, extend knowledge in several directions. I took advantage of the fact that their religion holds in reverence monstrous and imbecile forms of human beings. That is, of course, a common phenomenon in many countries, where half-wits are supposed to be inspired, and dwarfs the object of superstitious awe. So I went to work to create various new types. By employing a particular extract of adrenal cortex, I produced children who would have been a match for the Infant Hercules, and, indeed, looked rather like a cross between him and a brewer’s drayman. By injecting the same extract into adolescent girls I was able to provide them with the most copious mustaches, after which they found ready employment as prophetesses.

“Tampering with the post-pituitary gave remarkable cases of obesity. This, together with the passion of the men for fatness in their women, Bugala took advantage of, and I believe made quite a fortune by selling as concubines female slaves treated in this way. Finally, by another pituitary treatment, I at last mastered the secret of true dwarfism, in which perfect proportions are retained.

“Of these productions, the dwarfs are retained as acolytes in the temple; a band of the obese young ladies form a sort of Society of Vestal Virgins, with special religious duties, which, as the embodiment of the national ideal of beauty, they are supposed to discharge with peculiarly propitious effect; and the giants form our Regular Army.

“The Obese Virgins have set me a problem which I confess I have not yet solved. Like all races who set great store by sexual enjoyment, these people have a correspondingly exaggerated reverence for virginity. It therefore occurred to me that if I could apply Jacques Loeb’s great discovery of artificial parthenogenesis to man, or, to be precise, to these young ladies, I should be able to grow a race of vestals, self-reproducing yet ever virgin, to whom in concentrated form should attach that reverence of which I have spoken. You see, I must always remember that it is no good proposing any line of work that will not benefit the national religion. I suppose state-aided research would have much the same kinds of difficulties in a really democratic state. Well this, as I say, has so far beaten me. I have taken the matter a step further than Bataillon with his fatherless frogs, and I have induced parthenogenesis in the eggs of reptiles and birds; but so far I have failed with mammals. However, I’ve not given up yet!”

Then we passed to the next laboratory, which was full of the most incredible animal monstrosities. “This laboratory is the most amusing,” said Hascombe. “Its official title is ‘Home of the Living Fetishes.’ Here again I have simply taken a prevalent trait of the populace, and used it as a peg on which to hang research. I told you that they always had a fancy for the grotesque in animals, and used the most bizarre forms, in the shape of little clay or ivory statuettes, for fetishes.

“I thought I would see whether art could not improve upon nature, and set myself to recall my experimental embryology. I use only the simplest methods. I utilize the plasticity of the earliest stages to give double-headed and cyclopean monsters. That was, of course, done years ago in newts by Spemann and fish by Stockard; and I have merely applied the mass-production methods of Mr. Ford to their results. But my specialties are three-headed snakes, and toads with an extra heaven-pointing head. The former are a little difficult, but there is a great demand for them, and they fetch a good price. The frogs are easier: I simply apply Harrison’s methods to embryo tadpoles.”

He then showed me into the last building. Unlike the others, this contained no signs of research in progress, but was empty. It was draped with black hangings, and lit only from the top. In the center were rows of ebony benches, and in front of them a glittering golden ball on a stand.

“Here I am beginning my work on reinforeed telepathy,” he told me. “Some day you must come and see what it’s all about, for it really is interesting.”

You may imagine that I was pretty well flabbergasted by this catalogue of miracles. Every day I got a talk with Hascombe, and gradually the talks became recognized events of our daily routine. One day I asked if he had given up hope of escaping. He showed a queer hesitation in replying. Eventually he said, “To tell you the truth, my dear Jones, I have really hardly thought of it these last few years. It seemed so impossible at first that I deliberately put it out of my head and turned with more and more energy, I might almost say fury, to my work. And now, upon my soul, I am not quite sure whether I want to escape or not.”

“Not want to!” I exclaimed, “surely you can’t mean that!”

“I am not so sure,” he rejoiced. “What I most want is to get ahead with this work of mine. Why, man, you don’t realize what a chance I’ve got! And it is all growing so fast — I can see every kind of possibility ahead”; and he broke off into silence.

However, although I was interested enough in his past achievements; I did not feel willing to sacrifice my future to his perverted intellectual ambitions. But he would not leave his work.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.