A VICTIM OF HIGHER SPACE (4)

By:

June 19, 2022

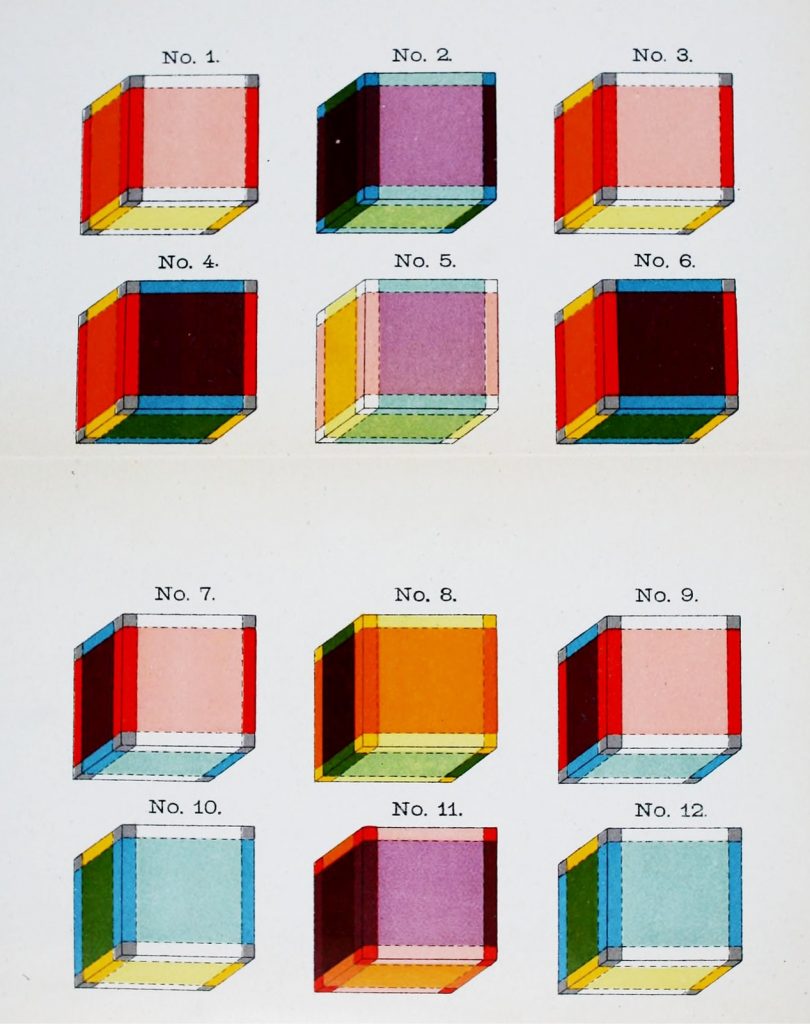

Images from The Fourth Dimension, a 1904 book about the “tesseract” — a four-dimensional analog of the cube — by Charles Howard Hinton, the British proto-sf writer who coined the term in 1888.

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Algernon Blackwood’s 1914 proto-sf story “A Victim of Higher Space” — featuring the occult investigator, mystic, and clairvoyant John Silence, about whom Blackwood would write five other stories — for HILOBROW’s readers. Here, Blackwood grapples playfully with the notion of a spatial fourth dimension — asking us to imagine how humans might experience or imagine a space extended in an extra dimensions they could not see.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9.

He drew a chair up beside his interlocutor and laid a hand on his shoulder for a moment. His whole being radiated kindness, intelligence, desire to help.

“For instance,” he went on, “I feel sure it was the result of no mere chance that you became familiar with the terrors of what you term Higher Space; for Higher Space is no mere external measurement. It is, of course, a spiritual state, a spiritual condition, an inner development, and one that we must recognise as abnormal, since it is beyond the reach of the world at the present stage of evolution. Higher Space is a mythical state.”

“Oh!” cried the other, rubbing his birdlike hands with pleasure, “the relief it is to be able to talk to some one who can understand! Of course what you say is the utter truth. And you are right that no mere chance led me to my present condition, but, on the other hand, prolonged and deliberate study. Yet chance in a sense now governs it. I mean, my entering the condition of Higher Space seems to depend upon the chance of this and that circumstance. For instance, the mere sound of that German band sent me off. Not that all music will do so, but certain sounds, certain vibrations, at once key me up to the requisite pitch, and off I go. Wagner’s music always does it, and that band must have been playing a stray bit of Wagner. But I’ll come to all that later. Only first, I must ask you to send away your man from the spy-hole.”

John Silence looked up with a start, for Mr. Mudge’s back was to the door, and there was no mirror. He saw the brown eye of Barker glued to the little circle of glass, and he crossed the room without a word and snapped down the black shutter provided for the purpose, and then heard Barker snuffle away along the passage.

“Now,” continued the little man in the chair, “I can begin. You have managed to put me completely at my ease, and I feel I may tell you my whole case without shame or reserve. You will understand. But you must be patient with me if I go into details that are already familiar to you — details of Higher Space, I mean — and if I seem stupid when I have to describe things that transcend the power of language and are really therefore indescribable.”

“My dear friend,” put in the other calmly, “that goes without saying. To know Higher Space is an experience that defies description, and one is obliged to make use of more or less intelligible symbols. But, pray, proceed. Your vivid thoughts will tell me more than your halting words.”

An immense sigh of relief proceeded from the little figure half lost in the depths of the chair. Such intelligent sympathy meeting him half-way was a new experience to him, and it touched his heart at once. He leaned back, relaxing his tight hold of the arms, and began in his thin, scale-like voice.

“My mother was a Frenchwoman, and my father an Essex bargeman,” he said abruptly. “Hence my name — Racine and Mudge. My father died before I ever saw him. My mother inherited money from her Bordeaux relations, and when she died soon after, I was left alone with wealth and a strange freedom. I had no guardian, trustees, sisters, brothers, or any connection in the world to look after me. I grew up, therefore, utterly without education. This much was to my advantage; I learned none of that deceitful rubbish taught in schools, and so had nothing to unlearn when I awakened to my true love — mathematics, higher mathematics and higher geometry. These, however, I seemed to know instinctively. It was like the memory of what I had deeply studied before; the principles were in my blood, and I simply raced through the ordinary stages, and beyond, and then did the same with geometry. Afterwards, when I read the books on these subjects, I understood how swift and undeviating the knowledge had come back to me. It was simply memory. It was simply re-collecting the memories of what I had known before in a previous existence and required no books to teach me.”

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.