Rolling in the Deep

By:

March 28, 2012

Science, like art and politics, follows the money. And these days, the motivated money is more likely to be in the hands of individuals than governments, like the kings of yore (although in yore kings were both individuals and governments…) So it may be fitting that James Cameron, the King of the 3D Film world, has not only funded, but undertaken the exploration of, one of the most remote areas on earth, the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench, a point under the oceans deeper than Everest is high. It is the lowest point on earth, without going in.

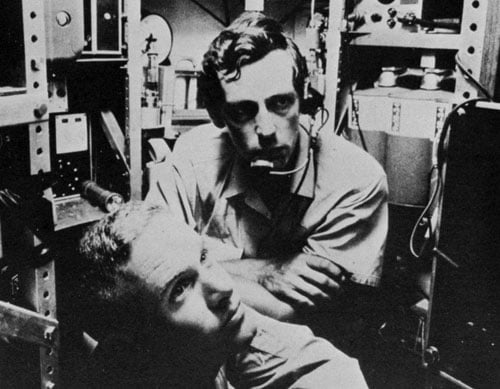

[Titanic, dir. James Cameron, 1997]

Cameron’s not the first. That honor goes to Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh, who in 1960 piloted a US Navy submersible to the bottom of the Deep, but stirred up so much sea-dust in their wake that nothing was visible, and the researchers surfaced with post-pressurized, empty hands.

And for the next half-century, the Deep waited…

The problem with water is the opposite of air. Venture too high, there’s not enough pressure; there’s not enough oxygen to breathe. Venture too deep, and there’s too much pressure – not only is the oxygen unhelpfully bonded to hydrogen, but the weight of the overhead oceans would crush you like a bug. Useful light reaches no further than 200 meters underwater; all photic traces cease by 1000 meters. Creatures of the deep, if any, are likely to be flat, small, and devoid of color, except in bioluminescent bursts.

[The Abyss, dir. James Cameron, 1989]

But oceans of possibility are contained in that “likely.” We don’t know because we haven’t seen what’s down there. Enter the filmmaker.

For this return to Flatland, Cameron expanded on the engineering he had already developed for deep-sea filming of the Titanic wreck. Long an oceanographic enthusiast, he has deepened his interest and deployed the technologies of simulated spectacle back into reality: his Mariana minisubmarine was of his own design, and he considers this release not a one-off, but the first in a series; he is planning sequels. The proof is in the production – his design works.

Of course he filmed the whole thing. In 3D.

In an age when everything has been explored, we are left with performance and reenactment. It is apt that the wizard of special effects should refocus his lenses from film-world to real-world vistas, using the technology of fantasy to reveal hidden aspects of reality. Any sufficiently hidden reality is indistinguishable from its portrayal on film. Hollywood at this point has so much practice in staging fake realistic spectacles, that it may be the natural place to turn for real-world engineering feats. This is the reverse of edutainment, where entertainment tropes (games, role-playing, videos, animation) are used to educate the viewer about some set of facts; in the nature documentary, facts are used to entertain.

[The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, dir. Wes Anderson, 2004]

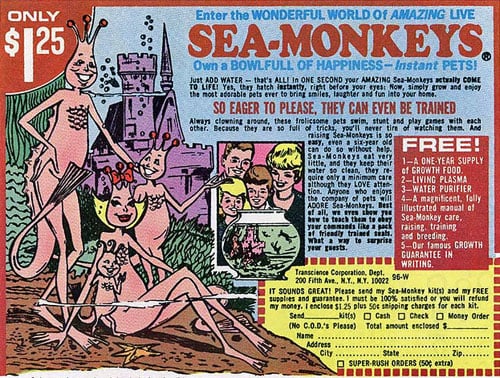

Perhaps tongue-in-cheek, Cameron expressed some mild dismay that no giant sea-monster swam into view. The only charismatic megafauna in the Mariana Trench is likely to be Cameron himself, but doubtless the highly-pressurized landscape at the bottom of the deep blue sea will yield transparently resilient sea-monkeys, the requisite rocks, and much meditation on humanity, and the abyss.

All this is not to disapprove. Quite the opposite. The intersecting set of art and science — and artists and scientists — is an area ripe for continued exploration. Again, Cameron wouldn’t be the first — there’s a long history including our own bioluminescent bursts like da Vinci and Lucretius. Cameron has cred this side of the silver screen; he is a National Geographic Society Explorer-in-Residence, and during the devastating oil spill in the Gulf in 2010 he volunteered use of his deep-sea subs, previously developed to film the wreck of the Titanic. But it is not without a healthy dose of irony that we note that the Magister Ludi of movies might bring his popular brand of hyperreality to bear on hyperreality itself.

There’s a poetic justice in having a filmmaker be both in front of and behind the camera: it echoes the artistry inherent in all scientific practice. In order to report your observations, you must create representations of them, whether textual, visual, numerical, schematical, or some combination thereof. Yet even the most precisely factual description of a thing, is still not the thing itself, and all representations contain aesthetic attributes. These attributes are easier to identify if you go further back in time, but our era they are no less present. Our scientific-aesthetic attributes are familiar (if usually overlooked); they include streamlined, clean, efficient, fast. To us, that’s just the color of science. But it’s not necessarily so. Eight hundred thousand years from now, the lichens and thermophiles ruling the hot flat places of the planet may think our science cartoonishly simplistic, theoretically clumsy, or even needlessly chaotic.

[The Time Machine, dir. Simon Wells, 2002]

But we are perhaps further from our own recent past than from some post-fauna future. As if to underscore our distance from the Heroic Age of Exploration, in mindset if not actual calendar years, Cameron described his own endeavor thus: “I’m hopeful that we’ll be able to study the ocean before we destroy it.”

Now there’s a half-full glass of salt water with a very concave meniscus.

Images of James Cameron and the Deepsea Challenger by Mark Theissen/National Geographic.

Read more about exploration on HiLobrow.

Read more about 3D on HiLobrow.