Nostalgia for the Now

By:

January 6, 2011

Photographs give us the ability to capture what we see, more or less. And apps give us the ability to capture what we wish. So what do we wish for? The seventies or a reasonable facsimile? More beautiful memories? A more beautiful everyday? A more beautiful war?

[Damon Winter, 2010]

Nostalgia is a tricky thing. It’s not just that apps like Hipstamatic add a fade and a blur, and a single-color cast to a scene, imbuing it with more presence than perhaps it had claimed for itself. That’s all right, presence is absent, it lives in the mind’s eye, if at all. Imbue at will. Nostalgia’s trickiness is measured in the values embedded in the algorithms. That striped t-shirt on your back? That empty afternoon coffee mug? That corpse with the artfully lifeless fingers? All gesturing towards some time in the past when life was slower, when colors had time to fade, when transitions were softer and easier on the heart, when possibilities beckoned. Never mind that there was no time like that; or rather, that all times are. In our memories, it exists. And in our digital outputs.

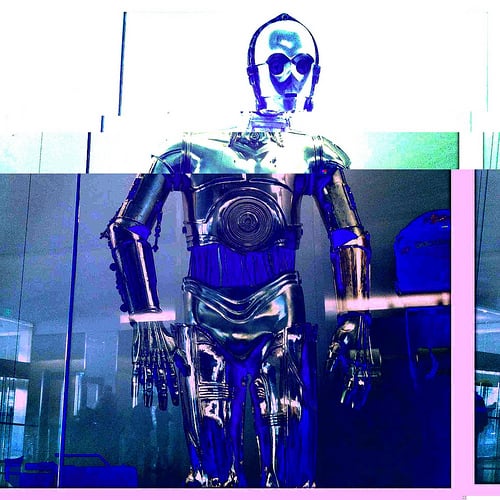

But memories actually exist in the now, as do apps. A new app, Decim8, attempts to take on the nostalgia challenge by introducing the look of digital artifacts: hard edges, high-chroma blocks of color, and partial repetition. Instead of mimicking errors of paper and ink, it celebrates errors of light and speed. The stutter replaces the fade.

[Chris Morris, Industry, 2010]

[à Rebours, C3P0, 2010]

And celebrate them it does; the abrupt, noisy images are a riot of color and angle. But hard edges don’t necessarily mean the here-and-now. Representation of computer display “glitches” can be just as sentimental as lowered contrast and softened edges. Digital stutter does not force pseudo-Modernist insight from the tiny lens. It’s another gloss on the past; albeit the recent past, as opposed to the less-recent past. Hey, remember the ’90s? And San Francisco? And Burning Man, and art school, and thinking that you still had, if not all the time in the world, then still some, and getting in on this internet thing . . . oh, sorry, my memories. Help yourself, though. Basically, nostalgia about the CRT-glitch look is to instamatic film as nostalgia about cassettes is to vinyl. It’s all nostalgia, unless you’re turning it to new purposes.

[à Rebours, Franklin, 2010]

And nostalgia, for all its trickiness, isn’t terrible, just problematic. It’s possible to have good memories, sure, or to segment and enhance the ones that were not really that good, instead of sinking into an overwhelmed bitterness like an inverted Benjaminian Angel. But nostalgia is not neutral. We need to remember, along with all the memories, that our lives in the now are partially cast from the look of our past. Maybe it’s fade and maybe it’s stutter, or maybe it’s different looks on different days.

[Andrei Molodkin, The Red and the Black (glass, oil and black-market blood), displayed at the 2009 Venice Biennale]

But whether you edge your memories in straight-up lines and hard angles, or soft fades and scribbles, whether you’re busy reconstructing or deconstructing, remember that your preferred nostalgic perspective is a design choice. One is not more virtuous. One is not more real. Pick your past, and design your future accordingly.