BROKEN KNOWLEDGE (10)

By:

November 13, 2025

University of Toronto philosopher Mark Kingwell and HILOBROW‘s Josh Glenn are coauthors of The Idler’s Glossary (2008), The Wage Slave’s Glossary (2011), and The Adventurer’s Glossary (2021). In 2022, they engaged in an epistolary exchange about science fiction. Via the series BROKEN KNOWLEDGE, the title of which references Francis Bacon’s philosophy, HILOBROW is pleased to share a lightly edited version of their exchange with our readers. Also see Josh and Mark’s previous exchange 49th PARALLEL.

BROKEN KNOWLEDGE: FIRST CONTACT | WHAT IF? | A HYBRID GENRE | COUNTERFACTUALS | A HOT DILUTE SOUP | I’M A CYBORG | APOPHENIC-CURIOUS | AN AESTHETICS OF DIRT | PAGING DR. KRISTEVA | POLICING THE GENRE | FAMILIAR STRANGENESS | GAME OVER | THE WORLD VIEWED | DEFAMILIARIZATION | SINGULAR CREATURES | ALIEN ARCHAEOLOGIST | THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF SCREEN-TIME | HOMO SUPERIOR | EVERYTHING IS US.

15th October, 2022

TORONTO GENERAL HOSPITAL

Before we let go of Never Let Me Go, I have to say how unreal it feels to be a transplant recipient, a potential member of the mostly invisible class of people who (spoiler!) enjoy the socio-scientific scheme described in Ishiguro’s book. Even without clones as unknowing organ donors, there are troubling ethical and political issues concerning organ transplants. I count myself among the very, very lucky ones in what amounts to a birthright lottery combined with unpredictable moral luck that then results in life-or-death schemes of distributive justice. Some people don’t hold with the idea of moral luck, fearing chaos and uncertainty if chance determines moral outcomes. But it does, of course; everyone should read Bernard Williams on the subject. Also, please fill out your donor card.

This is great genre stuff, Josh, especially about Campbell and the policing of ideological/gender/taste biases in American sf publishing. I feel as though the question of genre has been taken as far as we (literally you and I, not the general we) want to go. I use a version of that line about social realism being a genre often to my students. So many of them are Sort-of Janeites by inclination or declaration: they believe a novel must be a romance of some sort, with relatable characters, some conflict, and a (mostly) happy outcome. Money, politics, fashion, and architecture, say, may be involved; but the story is about universal issues, or ones that aspire to be. Or there are the neo-Goth kids — maybe neo-neo-Goth now — who drop into a cold-comfort bath of existential angst, as some undergraduates always have.

And that’s great — I did it myself. But what if Sartre’s No Exit had been decisively interpreted as speculative fiction, not social and ethical analysis? (It sometimes is.) Beckett’s Waiting for Godot is unimaginable without sf, in my mind — though I suppose the blasted heath as crucible of human fragility goes back at least to Lear. But people would lose their minds if you “relegated” these plays to the sf shelves.

Personally, I want to read Jane Austen, Shakespeare, Sartre, Camus, and a thousand others because they have something to say to me — the complicated pleasure of the text, as Martin Amis put it. And in such bountiful bibliomaniacal circumstances, to paraphrase another figure with a small vocabulary but a larger audience, genre is as genre does. Even just English novelists of a certain period, say, vary wildly in tone and theme. Graham Greene would say that the second last sentence has too many commas; Evelyn Waugh would say it has too few. These two masters of the English novel were born within a year of each other, 1903 and 1904, not many miles apart, and were both (eventually) Roman Catholic; but Greeneland is a long way from Waugh’s World.

I knew some of that publishing background, of course, but the stats on frequency of publication in the top pulps, and the exclusive of women, are striking features worth calling out in the way you do. Also, using Kristeva as a fulcrum here, making my earlier clean/dirty distinction into the anti-abject/abject binary is powerful. Asimov was a creep, as we know, and the quotation doesn’t surprise me, but we have to recall the long history of cultures viewing women’s bodies, especially with respect to functionality, with awe and suspicion, even anger.

I’m not going to suggest that there is such a thing as uterus envy, but the ability of women to carry children to term and thus assume, in many forms of social life, a moral if not physical authority, is decisive. Leaky female bodies, everywhere around these forward-thinking male writers, must have been a kind of nightmare! And romance — which produces in some cases the most decisive body breach of all, giving birth to another human — is icky to the point of mania. This is a combination of sad arrested development and compensatory aggression and denigration that we know too well. Also segregation! I don’t know about you, but my father was not present when my two siblings and I were born. I mean, he was in the hospital, but he was out in some TV lounge with other expectant dads, smoking cigarettes like someone in an old New Yorker cartoon.

Alien really is the key film here. Its importance is underrated by some critics and many philosophers, but the Oxford philosopher Stephen Mulhall makes an excellent case for it being an example of film doing philosophy. (He attempts the same feat with the Mission Impossible franchise, with less success).

Alien features everything we’ve been discussing: dirt, permeability, leaking (the whole ship is dripping so much that you can’t tell the alien invader from the cables and pipes). As Mulhall suggests, the franchise begins with a kind of rape, when the hapless John Character is impregnated with a nascent alien and then explosively “give birth” when it explodes of his chest. The main character, Sigourney Weaver’s Ripley, is a complicated mix of fierce and compassionate. The evolution of this character across the films is what makes them watchable, even entrancing. In the end, Ripley is the mother of mothers, battling another maternal that is, well, alien.

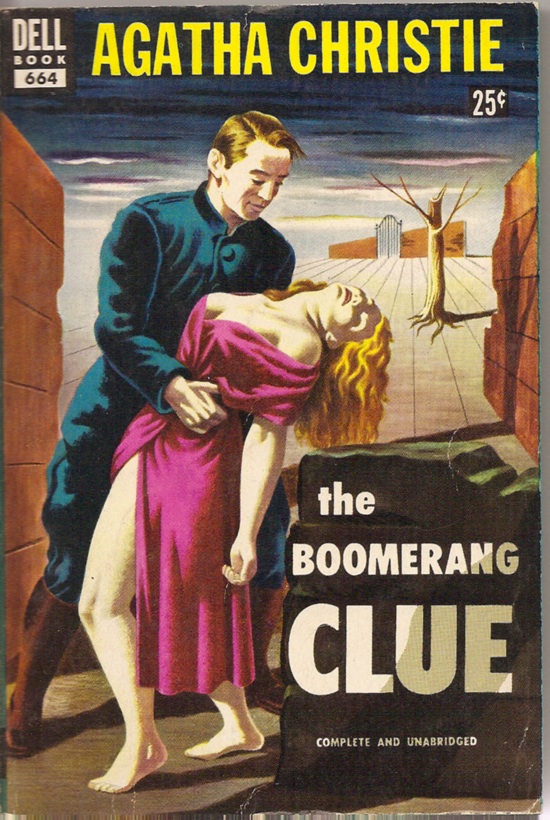

I have two things I wanted to say, one quick and one that will take a little longer to compose. The quick point is that the culture of the pulps, in all genres, was pretty decisively male from the beginning of the mass marketing of paperbacks. Crime, westerns, and sf appeared on the same spinning racks in drug stores or at cigar stands, maybe at the five-and-dime. They weren’t to be found in “nice” shops or department stores. So this lent a forbidden quality to browsing and buying pulp books, and an aura of misogynistic masculinity dominated their tough, often lurid covers. (You and I are both fans of the Hard Case Crime series of noir and thriller paperbacks, which revives this aesthetic, sometimes creepily.) Meanwhile, in a nice twist, efforts by high-brow publishers meant that the same wire racks that held Astounding and Mike Hammer might also have a 15-cent copy of Faulkner or Fitzgerald.

The second topic is the one I have avoided all throughout this note — the uncanny in film. Maybe this is my version of the return of the repressed? Anyway, right now some nurses want to put someone else’s harvested albumin into my veins.

Is that cool, gross, or weird? All of the above?

ALSO SEE: Josh’s BEST 250 ADVENTURES of the 20th CENTURY list | Mark on BATTLESTAR GALACTICA and THE HONG KONG CAVALIERS | Mark and Josh’s exchange 49th PARALLEL.