SEMIOPUNK (40)

By:

December 5, 2025

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

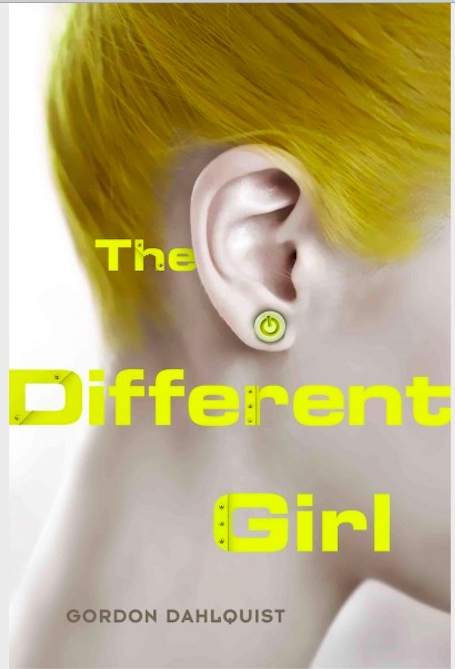

THE DIFFERENT GIRL

The Different Girl (2013) is an unsettling exploration of identity, consciousness, the nature of humanity… and how we know what we know. Very timely — ahead of its time — for our AI moment.

HILOBROW friend Gordon Dahlquist’s YA sf novella introduces us to red-headed Veronika — our precise, stilted, extremely literal narrator. One might imagine that she’s the titular different girl, but that would be too easy! Veronika and the three other girls (Caroline, Isobel, Eleanor) with whom she lives on an isolated (possibly post-apocalyptic island), with caretakers Irene and Robbert, are identical. Except for their hair color, that is.

Having been raised in a controlled environment designed to teach them basic cognitive processes, the four girls share exactly similar thought processes. The way they perceive and think — logically, literally — leads them to live the same way. They follow a strict routine and accept the explanations they are given about their past (their parents died in a plane crash) and the outside world without question. Each night, the girls power themselves down for sleep.

The way we all perceive and think leads us to live certain ways. We are to some extent determined by the network of meaning within which we’ve been raised… and by our unthinking assumption that the way we take in information, process it, and behave are natural and normal. We’re all programmed, in a way, even if we aren’t actually robots.

This feels like a good place to quote D.H. Lawrence:

For listen! the ego-centric self is the same

as the machine

The ego running in its own complex and

disconnected motion

using all life only as power, as an engine

uses steam or gas

power to repeat its own egocentric motions

this is the machine incarnate:

and the robot is the machine incarnate

and the slave is the machine incarnate

and the hopeless inferior, he is the

machine incarnate

an engine of flesh, useless unless he is a

tool

of other men.

The arrival on the island of May, the “different girl,” who is the survivor of a shipwreck, disrupts the un-different girls’ structured world. Whereas Veronika and the others use purely logical language, and struggle with abstract thought, May is emotional, impulsive, and has a rich inner life.

Which leads Veronika to take a metaphorical step back, to become self-reflective and introspective. The way she thinks and speaks, the way she uses language, is denotative — she deals only in the literal meaning of words. She can tell you precisely what she sees and does, but she lacks connotation — the associative, cultural, or emotional baggage of a word. She cannot use metaphor or understand figures of speech. Thanks to May’s influence, Veronika begins to question her own experience… and emerge as a distinct individual.

Semioticans can relate. Not, I hasten to add, that semioticians are strikingly more liberated than others. But it’s our job — literally — to explore connotation. To unpack latent unspoken associations. To question the “dominant” way that we and others in our culture perceive and respond to cultural and marketing prompts and cues. Each new project is a “different girl,” challenging us to un-know what we think we know.

The intrusion of the “different girl” on Veronika’s island is an epistemological catastrophe. It’s precisely this sort of catastrophe that semioticians attempt to inflict upon ourselves, for each project. And then we attempt to inflict it upon our clients. We attempt to un-know what we thought was natural, normal, eternal, inevitable.

Veronika’s rigorous training in (inductive) observing, reporting, and learning are not to be discounted. Semioticians rely on inductive ratiocination as well. It’s thanks to such “robotic” skills that Veronika now begins to notice that she’s been indoctrinated, that she is an inmate in a kind of invisible prison. She begins to suspect that a soul that cannot grasp the figurative is a soul fundamentally severed from the richness of shared human experience. Authenticity demands a traumatic break with the usual.

Gordon Dahlquist’s exquisite little parable reminds us that to be truly human is to be able to navigate and adapt to an infinitely complex, ever-changing, and often contradictory universe of signs.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.