THIS: No Immunity

By:

November 27, 2017

Loss is the signature experience of the new century — coastlines washing away; cities bombed into history; families shattered by war, migration, and official indifference. An earlier era of uncertainty and scarcity produced vigilante fantasy that was about how to survive, preemptively, against imagined enemies; the successors to this genre today are about how those left after the fire just live on.

As we know, the death-cycle is the one that’s more endless. We first saw Frank Castle, military genius and unstoppable murder-machine, in the second season of Netflix/Marvel’s Daredevil, fighting a one-man war on the Mob, whose own turf battles made collateral damage of Castle’s civilian family; in his solo series, The Punisher, we learn that the wrongs done to (and by) Castle stretch back to his overseas service, and up to the highest halls of government power. The fight has never ended, but the sides have become ever more shadowy.

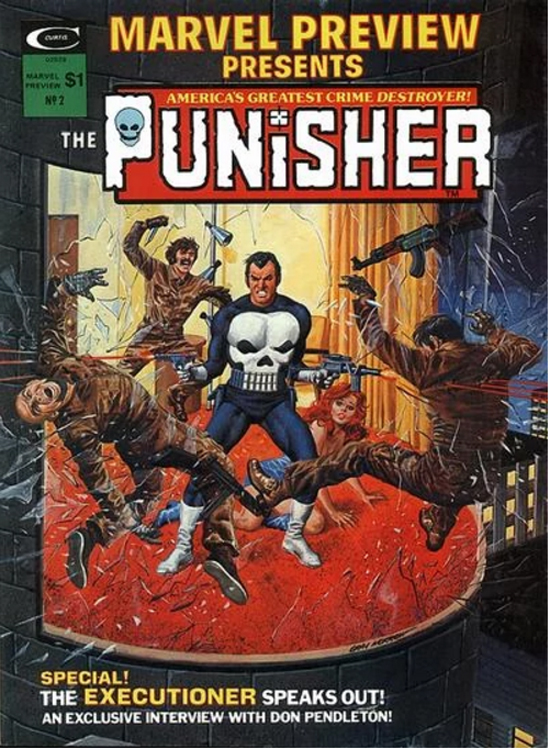

The Punisher comes from a special pedigree of exploitation; in the 1970s, Marvel Comics was mercantile enough to try and convert every social trend of the times into a comic concept, but too mindful of its pop-scholarly brand’s prestige to just crank out transparent tie-ins. Thus (to name but a few of these experiments) the stunt culture of Evel Knievel was morphed into the Faustian biker gothic of Ghost Rider; the aspirational schlock science of The Six Million Dollar Man was mirrored with the dystopian cyber-phobia of Deathlok; the Jesus Christ Superstar era of hippie devotion was allegorized in the cosmic passion-play of Warlock; and the vogue of urban-vigilante fiction went from Bickle and Bronson’s roving random madmen to The Punisher, a serial murderer with martial discipline and ambivalent morality-play overtones.

This spoke to several yearnings of the Nixon era — the Punisher only killed those who deserved it (mobsters, terrorists, etc.), thus feeding the hunger for moral certainty in lethal force that we had enjoyed during WWII and lacked in the then-current Vietnam conflict; while giving people across the political spectrum a cathartic fantasy for the failings of law-enforcement that both conservatives and liberals perceived and felt endangered by.

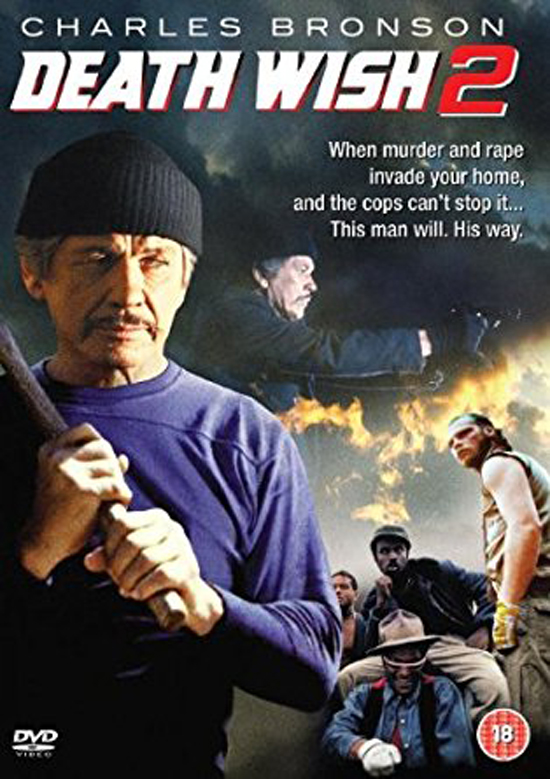

The Punisher comic owed more to Taxi Driver than to the Death Wish franchise; urban-commando Frank Castle, like Travis Bickle, feels he is duty-bound to cleanse predatory criminals from society, whereas Charles Bronson’s character in Death Wish is on a rampage of indiscriminate personal revenge. Bronson’s hunt is conspicuously racist while Bickle and Castle dispense equal-opportunity mayhem; though the comicbook Castle’s family fell as bystanders to a hit by “the Maggia,” Marvel later took care to establish that he himself is Italian, and the string of killings that opens the first episode of the Netflix version accounts for every head in the contemporary shooting-gallery of popular myth and social antagonism: dirtbag lower-class bikers; Mexican cartel warlords; whimpering white corporate oligarch.

Also in the first episode Frank’s former comrade in arms turned PTSD counselor Curtis goes so far as to liken one of the less sorted-out members of his therapy group to Travis from Taxi Driver. This is more than a media-studies hat-tip — the series lurks through the seedy tenements, alleyway wastelands and declining roadside diners of ’70s mass-market vérité; it is saturated with internet-era updates of the pervasive surveillance paranoia of the Watergate years and Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation; when Frank first appeared in comics, he was a psychologically scarred Vietnam vet, and this time it’s Afghanistan — movie tropes and social maladies are embodied by The Punisher’s cast and themes like a succession of ghosts moving through the same haunted house.

The phantom figure in the shadows of ’70s vigilante movies was our elusive national conscience; Bronson could slaughter some Black bogey-men and then pop back into the collective id, with no individual culpability. Frank Castle’s story was among the earliest versions of the form to critique the carnage while indulging it; some self-admonishment about the endless spiral and hollow satisfactions of vengeance was, I believe, one way to displace onto a fantasy anti-hero the “lesson” that Whites hoped would be borne in mind by the real-life dispossessed who we knew had good reason to take vengeance on us.

The Netflix Punisher crosses a lot of those gaps. The disposability felt by aggrieved lower-class White soldiers is shown alongside the marginalizing of Muslim patriots like Agent Madani, the Iranian-American DHS officer pursuing crimes and betrayals within the system she believes in. A blue-collar/gingham-collar divide is portrayed for laughs and played for keeps between Castle and the Snowden-esque hacker “Micro”; their gentry/grunt dichotomy mirrors the metro/heartland schism that defined the 2016 election. This antagonism has always been a faultline (and unifying seam) in Hollywood vigilante, slasher, and crazed-veteran fiction alike; we were meant to thrill to the backwoodsy Tobe Hooper-style killer hick, and the low-caste living weapon made to fight our wars or avenge our indignities. The irony of both the reactionary applause for and liberal mortification at the glorification of urban White exterminators and steroid-mutant Rambo/Commando types was that their films were being manufactured by people who’d probably never known a soldier or met a mechanic in their life. In Netflix’s Frank Castle we see a realistic range of working-class tastes (love of Springsteen, suspicion of hipsters, fierce loyalty to family, insistence on stealing only American cars) and singular quirks (guitar-strumming, poetry-quoting) that never slides into stereotype; a surviving strain of all-but-forgotten Studs Terkel-era respect for each of America’s social strata, and one we all need to make it home to.

The partitions are sturdy, and they all try to stay standing of their own accord: the antiseptic corridors of Madani’s office-complex are a world away from the dingy, squalid foxholes and dives Frank travels; and the soft-focus domestic shelters of his haunted flashbacks and Micro’s forsaken suburban home feel like a world that has never even existed — a well-staged metaphor for the unrealness that the returning vet, or hostage, patient, prisoner, feels upon attempted restoration to the life they left.

Dead worlds are enclosed with their occupants still lingering inside; at one point a video of the 1974 Ali/Frazier fight is playing on the TV of a character’s paneled rec-room (one of many remaindered symbols of upward mobility this show’s flawless, psychological location-scouting offers up); the fight, which is being watched over and over again by the character’s dad, is a faded symbol of perseverance lost on the man’s downward-spiraling son, a dropout from the vets-support group, who doesn’t understand who the fighters even are.

Old wounds flare up to fill a vast blankness; the untended, almost invisible scars of America’s 21st century perpetual wars get more screen-time in this series’ procession of damaged soldiers and dashed ideals than Abu Ghraib did in the entire Bush and Obama presidencies’ news cycles. As does the image of a home not just left behind, but rendered never the same again. Notwithstanding my special radar for the subject having suffered it myself, the Netflix Marvel series have a preoccupation with widowhood — Ben Urich caring for his cancer-battling wife in the first Daredevil season; Luke’s bereavement in both Jessica Jones and Luke Cage; and of course Castle’s creation in the crucible of his family’s murder in both Daredevil season two and now The Punisher. Frank’s mirror-image is Sarah, the surviving spouse of his presumed-dead ally Micro; in his Martin Guerre-like meeting with her, Frank gets to view the parallel reality of what his wife and kids would have suffered had he died instead of the other way round. And the containment of toxic masculinity and its collateral casualties is a central theme of the show, from the guidance offered by former-corpsman Curtis’ church-basement PTSD therapy-group, to the dominance rituals of various slimy CIA and security-state types, to the lashing out of both Frank’s and Sarah’s male children. These honestly recorded consequences are what redeem the decades of action-hero girlfriends who are nothing but cannon-fodder for the male protagonist’s outrage; in the Netflix series, they live, and suffer, and sometimes their roles are taken on by the heroes themselves. We don’t focus on what the “villains” do to them, we see what the heroes do to them (and to themselves).

Bodies that don’t even count are central to this series; often, some savage conflict or gruesome battlefield surgery will be quick-cut to desperate sex, or dreams of connubial bliss abruptly give way to bloodshed; one shootout is staged in an abandoned clothing factory, its naked scattered mannequins getting blown to bits like endless innocents, human decoys whose worth decreases with the sharpness of someone’s aim.

Metaphor never takes over, though; both the buried past and the falsified present catch up with the characters, and, whereas the social-issues cinema of the ’60s and ’70s that this series evokes would claim to be “torn from today’s headlines,” The Punisher crashes into the 24-hour media environment, its imprint of collective nightmare feeling much more lived-in than many of its models. The later episodes confront domestic terrorism and gun-control controversies head-on and in the open, and while not everything can be resolved in the heat of the fray, the show takes a clear-eyed look at what everyone saw at the time.

In the canon of cautionary revenge parables, this version of The Punisher remains uninfected by its subject-matter to a remarkable, maybe unprecedented degree. Even when it seems to fall over the edge, its sense of consequences kicks back in — as in a part self-defense, part ambush bloodbath in Episode 11 that seems creepily cathartic but turns out to be nowhere near as worth-it as Frank thought. And the way he reverts to a composed, fatherly figure one or two scenes later is a portrait of compartmentalized psychosis that sets anyone who sees it on a spiral of reassurance and uncertainty.

In an unbroken circle of violence, no climactic confrontation is the final one, and those in the series’ concluding episodes feel endless — but wanting them to stop is a sign of the filmmakers’ accomplishment. This is not the blood-ballet of some slow-motion gangster-saga or gore-Western of the ’60s era; it’s sheer brutality and superlative sickness, scaring everyone as it should, and sparing no conscience as it must.

And while there may seldom or never be such a thing as a happy ending, there’s always an aftermath. The tense, stunned calm at the end of The Punisher, closing on a note of battered tenderness like nothing else in the action-movie canon, does not guarantee that any business will ever be finished, but leaves a clear field yet to cross.

MORE POSTS by ADAM McGOVERN: OFF-TOPIC (2019–2025 monthly) | textshow (2018 quarterly) | PANEL ZERO (comics-related Q&As, 2018 monthly) | THIS: (2016–2017 weekly) | PEOPLE YOU MEET IN HELL, a 5-part series about characters in McGovern’s and Paolo Leandri’s comic Nightworld | Two IDORU JONES comics by McGovern and Paolo Leandri | BOWIEOLOGY: Celebrating 50 years of Bowie | ODD ABSURDUM: How Felix invented the 21st century self | CROM YOUR ENTHUSIASM: C.L. Moore’s JIREL OF JOIRY stories | KERN YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Data 70 | HERC YOUR ENTHUSIASM: “Freedom” | KIRK YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Captain Camelot | KIRB YOUR ENTHUSIASM: Full Fathom Five | A 5-part series on Jack Kirby’s Fourth World mythos | Reviews of Annie Nocenti’s comics Katana, Catwoman, Klarion, and Green Arrow | The curated series FANCHILD | To see all of Adam’s posts, including HiLo Hero items on Lilli Carré, Judy Garland, Wally Wood, and others: CLICK HERE