A Rogue By Compulsion (8)

By:

May 19, 2016

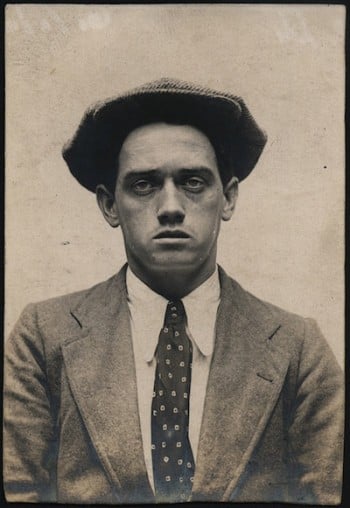

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

That journey of mine to London stands out in my memory with extraordinary vividness. I don’t think I shall ever forget the smallest and most unimportant detail of it. The truth is, I suppose, that my whole mind and senses were in an acutely impressionable state after lying fallow, as they practically had, for over three years. Besides, the sheer pleasure of being out in the world again seemed to invest everything with an amazing interest and wonder.

It was just half-past one when Savaroff brought the car round to the front door. I was standing in the hall talking to McMurtrie, who had decided not to accompany us into Plymouth. Of Sonia I had seen nothing since our unfortunately interrupted interview in the morning.

“Well,” said the doctor, as with a grinding of brakes the car pulled up outside, “we can look on this as the real beginning of our little enterprise.”

I picked up my Gladstone. “Let’s hope,” I said, “that the end will be equally satisfactory.”

McMurtrie nodded. “I fancy,” he said, “that we need have no apprehensions. Providence is with us, Mr. Lyndon — Providence or some equally effective power.”

There was a note of irony in his voice which left one in no doubt as to his own private opinion of our guiding agency.

I stepped out into the drive carrying my bag. Savaroff, who was sitting in the driving seat of the car, turned half round towards me.

“Put it on the floor at the back under the rug,” he said. “You will sit in front with me.”

He spoke in his usual surly fashion, but by this time I had become accustomed to it. So contenting myself with a genial observation to the effect that I should be charmed, I tucked the bag away out of sight and clambered up beside him into the left-hand seat. McMurtrie stood in the doorway, that mirthless smile of his fixed upon his lips.

“Good-bye,” I said; “we shall meet at Tilbury, I suppose — if not before?”

He nodded. “At Tilbury certainly. Au revoir, Mr. Nicholson.”

And with this last reminder of my future identity echoing in my ears, we slid off down the drive.

All the way into Plymouth Savaroff maintained a grumpy silence. He was naturally a taciturn sort of person, and I think, besides that, he had taken a strong dislike to me from the night we had first seen each other. If this were so I had certainly not done much to modify it. I felt that the man was naturally a bully, and it always pleases and amuses me to be disliked by bullies. Indeed, if I had had no other reason for responding to Sonia’s proffered affection I should have done so just because Savaroff was her father.

My companion’s sulks, however, in no way interfered with my enjoyment of the drive. It was a perfect day on which to regain one’s liberty. The sun shone down from a blue sky flecked here and there with fleecy white clouds, and on each side of the road the hedges and trees were just beginning to break into an almost shrill green. The very air seemed to be filled with a delicious sense of freedom and adventure.

As we got nearer to Plymouth I found a fresh source of interest and pleasure in the people that we passed walking along the road or driving in traps and cars. After my long surfeit of warders and convicts the mere sight of ordinarily-dressed human beings laughing and talking filled me with the most intense satisfaction. On several occasions I had a feeling that I should like to jump out of the car and join some group of cheerful-looking strangers who turned to watch us flash past. This feeling became doubly intense when we actually entered Plymouth, where the streets seemed to be almost inconveniently crowded with an extraordinary number of attractive-looking girls.

I was afforded no opportunity, however, for indulging in any such pleasant interlude. We drove straight through the town at a rapid pace, avoiding the main thoroughfares as much as possible, and not slackening until we pulled up outside Millbay station. We left the car in charge of a tired-looking loafer who was standing in the gutter, and taking out my bag, I followed Savaroff into the booking office.

“You had better wait there,” he muttered, pointing to the corner. “I will get the ticket.”

I followed his suggestion, and while he took his place in the small queue in front of the window I amused myself watching my fellow passengers hurrying up and down the platform. They looked peaceful enough, but I couldn’t help picturing what a splendid disturbance there would be if it suddenly came out that Neil Lyndon was somewhere on the premises. The last time I had been in this station was on my way up to Princetown two and a half years before.

At last Savaroff emerged from the throng with my ticket in his hand.

“I have taken you a first-class,” he said rather grudgingly. “You will probably have the carriage to yourself. It is better so.”

I nodded. “I shouldn’t like to infect any of these good people with homicidal mania,” I said cheerfully.

He looked at me rather suspiciously — I think he always had a sort of vague feeling that I was laughing at him — and then without further remark led the way out on to the platform.

McMurtrie had given me a sovereign and some loose silver for immediate expenses, and I stopped at the bookstall to buy myself some papers. I selected a Mail, a Sportsman, Punch, and the Saturday Review. I lingered over the business because it seemed to annoy Savaroff: indeed it was not until he had twice jogged my elbow that I made my final selection. Then, grasping my bag, I marched up the platform behind him, coming to a halt outside an empty first-class carriage.

“This will do,” he said, and finding no sound reason for contradicting him I stepped in and put my bag upon the rack.

“Good-bye, Savaroff,” I said cheerfully. “I shall have the pleasure of seeing you too at Tilbury, I suppose?”

He closed the door, and thrust his head in through the open window.

“You will,” he said in his guttural voice; “and let me give you a little word of advice, my friend. We have treated you well — eh, but if you think you can in any way break your agreement with us you make a very bad mistake.”

I took out my cigarette case. “My dear Savaroff,” I said coldly, “why on earth should I want to break my agreement with you? It is the only possible chance I have of a new start.”

He looked at me closely, and then nodded his head. “It is well. So long as you remember we are not people to be played with, no harm will come to you.”

He let this off with such a dramatic air that I very nearly burst out laughing.

“I shan’t forget it,” I said gravely. “I’ve got a very good memory.”

There was a shrill whistle from the engine, followed by a warning shout of “Stand back there, please; stand back, sir!” I had a last glimpse of Savaroff’s unpleasant face, as he hurriedly withdrew his head, and then with a slight jerk the train began to move slowly out of the station.

I didn’t open my papers at once. For some time I just sat where I was in the corner and stared out contentedly over the passing landscape. There is nothing like prison to broaden one’s ideas about pleasure. Up till the time of my trial I had never looked on a railway journey as a particularly fascinating experience; now it seemed to me to be simply chock-full of delightful sensations. The very names of the stations — Totnes, Newton Abbot, Teignmouth — filled me with a sort of curious pleasure: they were part of the world that I had once belonged to — the gay, free, jolly world of work and laughter that I had thought lost to me for ever. I felt so absurdly contented that for a little while I almost forgot about George.

The only stop we made was at Exeter. There were not many people on the platform, and I had just decided that I was not going to be disturbed, when suddenly a fussy-looking little old gentleman emerged from the booking office, followed by a porter carrying his bag. They came straight for my carriage.

The old gentleman reached it first, and puckering up his face, peered in at me through the window. Apparently the inspection was a success.

“This will do,” he observed. “Leave my bag on the seat, and go and see that my portmanteau is safely in the van. Then if you come back here I will give you threepence for your trouble.”

Dazzled by the prospect, the porter hurried off on his errand, and with a little grunt the old gentleman began to hoist himself in through the door. I put out my hand to assist him.

“Thank you, sir, thank you,” he remarked breathlessly. “I am extremely obliged to you, sir.”

Then, gathering up his bag, he shuffled along the carriage, and settled himself down in the opposite corner.

I was quite pleased with the prospect of a fellow passenger, unexciting as this particular one promised to be. I have either read or heard it stated that when people first come out of prison they feel so shy and so lost that their chief object is to avoid any sort of society at all. I can only say that in my case this was certainly not true. I wanted to talk to every one: I felt as if whole volumes of conversation had been accumulating inside me during the long speechless months of my imprisonment.

It was the old gentleman, however, who first broke our silence. Lowering his copy of the Times, he looked up at me over the top of his gold-rimmed spectacles.

“I wonder, sir,” he said, “whether you would object to having that window closed; I am extremely susceptible to draughts.”

“Why, of course not,” I replied cheerfully, and suiting my action to my words I jerked up the sash.

This prompt attention to his wishes evidently pleased him; for he thanked me civilly, and then, after a short pause, added some becoming reflection on the subject of the English spring.

It was not exactly an inspiring opening, but I made the most of it. Without appearing intrusive I managed to keep the conversation going, and in a few minutes we were in the middle of a brisk meteorological discussion of the most approved pattern.

“I daresay you find these sudden changes especially trying,” commented my companion. Then, with a sort of apology in his voice, he added: “One can hardly help seeing that you have been accustomed to a warmer climate.”

I smiled. “I have been out of England,” I said, “for some time”; and if this was not true in the letter, I don’t think that even George Washington could have found much fault with it in the spirit.

“Indeed, sir, indeed,” said the old gentleman. “I envy you, sir. I only wish my own duties permitted me to winter entirely abroad.”

“It has its advantages,” I admitted, “but in some ways I am quite pleased to be back again.”

My companion nodded his head. “For one thing,” he said, “one gets terribly behindhand with English news. I find that even the best of the foreign papers are painfully ill-informed.”

A sudden mischievous thought came into my head. “I have hardly seen a paper of any kind for a fortnight!” I said. “Is there any particular news? The last interesting thing I saw was about that young fellow’s escape from Dartmoor — that young inventor — what was his name? — who was in for murder.”

The old gentleman looked up sharply. “Ah! Lyndon,” he said, “Neil Lyndon you mean. He is still at large.”

“From what I read of the case,” I went on carelessly, “it seems rather difficult to help sympathizing with him — to a certain extent. The man he murdered doesn’t appear to have been any great loss to the community.”

My companion opened his mouth as if to speak, and then hesitated. “Well, as a matter of fact I am scarcely in a position to discuss the subject,” he said courteously. “Perhaps, sir, you are unaware who I am?”

He asked the question with a slight touch of self-conscious dignity, which showed me that in his own opinion at all events he was a person of considerable importance. I looked at him again more carefully. There seemed to be something familiar about his face, but beyond that I was utterly at sea.

“The fact is, I have been so much abroad,” I began apologetically —

He cut me short by producing a little silver case from his pocket and handing me one of his cards.

“Permit me, sir,” he said indulgently.

I took it and read the following inscription:

RT. HON. SIR GEORGE FRINTON, P.C. The Reform Club.

I remembered him at once. He was a fairly well known politician — an old-fashioned member of the Liberal Party, with whose name I had been more or less acquainted all my life. I had never actually met him in the old days, but I had seen one or two photographs and caricatures of him, and this no doubt explained my vague recollection of his features.

For just a moment I remained silent, struggling against a strong impulse to laugh. There was something delightfully humorous in the thought of my sitting in a first-class carriage exchanging cheerful confidences with a distinguished politician, while Scotland Yard and the Home Office were racking their brains over my disappearance. It seemed such a pity I couldn’t hand him back a card of my own just for the fun of watching his face while he read it.

MR. NEIL LYNDON Late of His Majesty’s Prison, Princetown.

Collecting myself with an effort, I covered my apparent confusion with a slight bow.

“It was very stupid of me not to have recognized you from your pictures,” I said.

This compliment evidently pleased the old boy, for he beamed at me in the most gracious fashion.

“You see now, sir,” he said, “why it would be quite impossible for me to discuss the matter in question.”

I bowed again. I didn’t see in the least, but he spoke as if the point was so obvious that I thought it better to let the subject drop. I could only imagine that he must be holding some official position, the importance of which he probably overrated.

We drifted off into the discussion of one or two other topics; settling down eventually to our respective newspapers. I can’t say I followed mine with any keen attention. My brain was too much occupied with my own affairs to allow me to take in very much of what I read. I just noticed that we were engaged in a rather heated discussion with Germany over the future of Servia, and that a well-meaning but short-sighted Anarchist had made an unsuccessful effort to shoot the President of the American Steel Trust.

Of my own affairs I could find no mention, beyond a brief statement to the effect that I was still at liberty. There was not even the usual letter from somebody claiming to have discovered my hiding-place, and for the first time since my escape I began to feel a little neglected. It was evident that as a news topic I was losing something of my first freshness.

The last bit of the journey from Maidenhead onwards seemed to take us an unconscionably long time. A kind of fierce restlessness had begun to get hold of me as we drew nearer to London, and I watched the fields and houses flying past with an impatience I could hardly control.

We rushed through Hanwell and Acton, and then suddenly the huge bulk of Wormwood Scrubbs Prison loomed up in the growing dusk away to the right of the line. It was there that I had served my “separates” — those first ghastly six months of solitary confinement which make even Princetown or Portland a welcome and agreeable change.

At the sight of that poisonous place all the old bitterness welled up in me afresh. For a moment even my freedom seemed to have lost its sweetness, and I sat there with my hands clenched and black resentment in my heart, staring out of those grim unlovely walls. It was lucky for George that he was not with me in the carriage just then, for I think I should have wrung his neck without troubling about any explanations.

I was awakened from these pleasant reflections by a sudden blare of light and noise on each side of the train. I sat up abruptly, with a sort of guilty feeling that I had been on the verge of betraying myself, and letting down the window, found that we were steaming slowly into Paddington Station. In the farther corner of the carriage my distinguished friend Sir George Frinton was beginning to collect his belongings.

I just had time to pull myself together when the train stopped, and out of the waiting line of porters a man stepped forward and flung open the carriage door. He was about to possess himself of my fellow passenger’s bag when the latter waved him aside.

“You can attend to this gentleman,” he said. “My own servant is somewhere on the platform.” Then turning to me, he added courteously: “I wish you good-day, sir. I am pleased to have made your acquaintance. I trust that we shall have the mutual pleasure of meeting again.”

I shook hands with him gravely. “I hope we shall,” I replied. “It will be a distinction that I shall vastly appreciate.”

And of all unconscious prophecies that were ever launched, I fancy this one was about the most accurate.

Preceded by the porter carrying my bag, I crossed the platform and stepped into a waiting taxi.

“Where to, sir?” inquired the man.

I had a sudden wild impulse to say: “Drive me to George,” but I checked it just in time.

“You had better drive me slowly along Oxford Street,” I said. “I want to stop at one or two shops.”

The man started the engine and, climbing back into his seat, set off with a jerk up the slope. I lay back in the corner, and took in a long, deep, exulting breath. I was in London — in London at last —and if those words don’t convey to you the kind of savage satisfaction that filled my soul you must be as deficient in imagination as a prison governor.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.