A Rogue By Compulsion (12)

By:

June 20, 2016

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

I have never been slow to act in moments of sudden emergency, and in rather less than a second I had made up my mind. The mere idea of stalking one’s own shadower was a distinctly attractive one; surrounded as I was by a baffling sense of mystery and danger I jumped at the chance with an almost reckless enthusiasm.

Coming up behind was another taxi — an empty one, the driver leaning back in his seat puffing lazily at a pipe. I stepped out into the road and signalled to him to pull up.

“Follow that taxi in front,” I said quickly. “If you keep it in sight till it stops I’ll give you five shillings for yourself.”

All the languor disappeared from the driver’s face. Hastily knocking out his pipe, he stuffed it into his pocket, and the next moment we were bowling up Victoria Street hard on the track of our quarry.

I sat back in the seat, filled with a pleasant exhilaration. Of course it was just possible that I was making a fool of myself — that the gentleman in front was as innocent of having spied on my movements as the Bishop of London. Still if that were the case there could be no harm in following him, while if he were really one of McMurtrie’s friends a closer acquaintance with his methods of spending the evening seemed eminently desirable.

Half way along Whitehall my driver quickened his pace until we were only a few yards behind the other taxi. I was just going to caution him not to get too near, when I realized that unless we hung on as close as possible we should probably lose it in the traffic at the corner of the Strand. The soundness of this reasoning was apparent a moment later, when we only just succeeded in following it across the Square before a policeman’s hand peremptorily barred the way.

Past the Garrick Theatre, across Long Acre, and up Charing Cross Road the chase continued with unabated vigour. At the Palace the other driver turned off sharp to the left, and running a little way along Old Compton Street came to a halt outside Parelli’s, the well-known restaurant. As he began to slow down I picked up the speaking tube and instructed my man to go straight past on the other side of the street, an order which he promptly obeyed without changing his pace. I didn’t make the mistake of looking round. I just sat still in my seat until we had covered another thirty yards or so, and then gave the signal to stop.

The driver, who seemed to have entered thoroughly into the spirit of the affair, at once clambered out of his seat and came round as though to open the door.

“Gent’s standin’ on the pavement payin’ ‘is fare, sir,” he observed in a hoarse whisper. “Thought ye might like to know before ye gets out.”

“Thanks,” I said; “I’ll take the chance of lighting a cigarette.”

I was about to suit the action to the word, when with a sudden exclamation the man again interrupted me.

“There’s another gent just come up in a taxi, sir — proper toff too from ‘is looks. ’E’s shakin’ ‘ands with our bloke.”

“Is he an old man?” I asked quickly — “an old man with glasses?”

“’E don’t look very old, but ’e’s got a glass right enough — leastways one o’ them bow-winder things in ’is eye.” He paused. “They’ve gone inside now, Guv’nor; they won’t spot ye if you want to ’op it.”

He opened the door, and stepping out on to the pavement I handed him half a sovereign, which I was holding in readiness.

He touched his cap. “Thank ye, sir. Thank ye very much.” Then, fumbling in his pocket, he produced a rather dirty and crumpled card. “I don’t rightly know what the game is, Guv’nor,” he went on in a lowered tone, “but if you should ‘appen to want to call on me for evidence any time, Martyn’s Garridge, Walham Green, ‘ll always find me. Ye only need to ask for Dick ‘Arris. They all knows me round there.”

I accepted the card, and having assured Mr. Harris that in the event of my needing his testimony I would certainly look him up, I lit my delayed cigarette and started to stroll back towards Parelli’s. Whoever my original friend and his pal with the eyeglass might be, I was anxious to give them a few minutes’ law before thrusting myself upon their society. I had known Parelli’s well in the old days, and remembering the numerous looking-glasses which decorated its walls, I thought it probable that I should be able to find some obscure seat, from which I could obtain a view of their table without being too conspicuous myself. Still, it seemed advisable to give them time to settle down to dinner first, so, stopping at a newspaper shop at the corner, I spun out another minute or two in buying myself a copy of La Vie Parisienne and the latest edition of the Pall Mall. With these under my arm and a pleasant little tingle of excitement in my heart I walked up to the door of the restaurant, which a uniformed porter immediately swung open.

I found myself in a brightly lit passage, inhabited by a couple of waiters, one of whom came forward to take my hat and stick. The other pushed back the glass door which led into the restaurant, and then stood there bowing politely and waiting for me to pass.

I stopped for a moment on the threshold, and cast a swift glance round the room. It was a large, low-ceilinged apartment, broken up by square pillars, but as luck would have it I spotted my two men at the very first attempt. They were sitting at a table in one of the farther corners, and they seemed to be so interested in each other’s company that neither of them had even looked up at my entrance.

I didn’t wait for them to do it either. Quickly and unobtrusively I walked to the corner table on the left of the floor, and sat down with my back towards them. I was facing a large mirror which reflected the other side of the room with admirable clearness.

A waiter handed me the menu, and after I had ordered a light dinner I spread out La Vie Parisienne on the table, and bending over it made a pretence of admiring its drawings. As a matter of fact I kept my entire attention focused on the looking-glass.

I could only see the back of the man with the scar, but the face of his companion, who was sitting sideways on, was very plainly visible. It was a striking-looking face, too. He seemed to be about thirty-five — a tall, clean-shaven, powerfully built man, with bright blue eyes and a chin like the toe of a boot. His hair was prematurely grey, and this, together with the monocle that he was wearing, gave him a curious air of distinction. He looked like a cross between a successful barrister and a retired prize-fighter.

I watched him with considerable interest. If he was another of McMurtrie’s mysterious circle, I certainly preferred him to any of the ones I had previously come across. His face, though strong and hard, had none of Savaroff’s brutality in it, and he was quite lacking in that air of sinister malevolence that seemed to hang about the doctor.

As far as I could see, most of the talking was being done by the man with the scar. He also appeared to be the host, for I saw him pick up the wine list, and after consulting his companion’s taste give a carefully selected order to the waiter. Then my own dinner began to arrive, and putting aside La Vie, I propped up the Pall Mall in front of me and started to attack the soup.

All through the meal I divided my attention between the paper and the looking-glass. I was careful how I made use of the latter, for the waiter was hovering about most of the time, and I didn’t want him to think that I was spying on some of the other customers. So quite genuinely I waded through the news, keeping on glancing in the mirror over the top of the paper from time to time just to see how things were progressing behind me.

That my two friends were getting along together very well was evident not only from their faces but from the sounds of laughter which at intervals came floating down the room. Indeed, so animated was their conversation, that although I had begun my dinner later, I had finished some little time before they had. I had no intention of leaving first, however, so ordering myself some coffee, I sat back in my chair, and with the aid of a cigar, continued my study of the Pall Mall.

I was in the middle of a spirited article on the German trouble, headed “What Does the Kaiser Mean?” when glancing in the mirror I saw a waiter advance to the table behind me, carrying a bottle of port in a basket, with a care that suggested some exceptional vintage. He poured out a couple of glasses, and then placing it reverently on the table, withdrew from the scene.

I watched both men take a sip, and saw them set down their glasses with a thoroughly satisfied air. Then the man with the scar made a sudden remark to the other, who, turning his head, looked away over his shoulder into the restaurant. His attention could only have been withdrawn from the table for a couple of seconds at the most, but in that fraction of time something happened which set my heart beating rapidly in a kind of cold and tense excitement.

So swiftly, that if I had not been looking straight in the mirror I should have missed seeing it, the man with the scar brought his hand down over his companion’s glass. Unless my eyes were playing me a trick, I distinctly saw him empty something into the wine.

There are rare occasions in life when one acts instinctively in the right way before one’s mind has had time to reason matters out. It was so with me now. Without stopping to think, I whipped out a pencil from my pocket, and snatched away a piece of white paper from underneath the small dish of candied fruit in front of me. Spreading it out on the table I hastily scribbled the following words:

“Don’t drink your wine. The man with you has just put something into it.”

I folded this up, and beckoned to one of the waiters who was standing by the door. He came forward at once.

“Do you want to earn half a sovereign?” I asked.

“Yes, sir,” he answered, without the faintest air of surprise.

“Listen to me, then,” I said, “and whatever you do don’t look round. In the farther corner behind us there’s a gentleman with an eyeglass dining with another man. Go up the centre of the room and give him this note. If he asks you who it’s from, say some one handed it you in the hall and told you to deliver it. Then go and get my bill and bring it me here.”

The waiter bowed, and taking the note departed on his errand, as casually as though I had instructed him to fetch me a liqueur. All the time I had been speaking I had kept a watchful eye on the mirror, and as far as I could tell neither of the two men had noticed our conversation. They were talking and laughing, the man I had sent the message to lightly fingering the stem of his wine-glass, and blowing thin spirals of cigarette smoke into the air. Even as I looked he raised the glass, and for one harrowing second I thought I was too late. Then, like a messenger from the gods, the waiter suddenly appeared from behind one of the pillars and handed him my note on a small silver tray.

He took it casually with his left hand; at the same time setting down his wine-glass on the table. I saw him make an excuse to his host, and then open it and read it. I don’t know exactly what I had expected him to do next, but the result was certainly surprising. Instead of showing any amazement or even questioning the waiter, he made some laughing remark to his companion, and putting his hand in his pocket pulled out a small leather case from which he extracted a card.

Bending over the table he wrote two or three words in pencil, and handed it to the waiter. As he did so the edge of his sleeve just caught the wine-glass. I saw the other man start up and stretch out his hand, but he was too late to save it. Over it went, breaking into pieces against one of the plates, and spilling the wine all across the table-cloth.

It was done so neatly that I could almost have sworn it was an accident. Indeed the exclamation of annoyance with which the culprit greeted his handiwork sounded so perfectly genuine that if I hadn’t known what was in the note I should have been completely deceived. I saw the waiter step forward and dab hurriedly at the stain with a napkin, while the author of the damage, coolly pulling up another glass, helped himself to a fresh supply from the bottle. A more beautifully carried out little bit of acting it has never been my good luck to witness.

If the man with the scar suspected anything (which I don’t think he did) he was at least intelligent enough to keep the fact to himself. He laughed heartily over the contretemps, and taking out his cigar-case offered his companion a choice of the contents. I saw the latter shake his head, raising his half-finished cigarette as much as to indicate his preference for that branch of smoking. It struck me, however, that his refusal was possibly dictated by other motives.

Full of curiosity as I was, I thought it better at this point not to tempt Fate any further. At any moment the man with the scar might look round, and although I was some distance away, it was quite likely that if he did he would recognize my reflection in the mirror. I was doubly anxious now to avoid any such mischance, so, picking up La Vie, I opened its immoral but conveniently spacious pages, and from behind their shelter waited for my bill.

It was not long in coming. Impassive as ever, the waiter reappeared with his little silver tray, which this time contained a white slip folded across in the usual fashion. As I took it up I felt something inside, and opening it I discovered a small visiting card with the following inscription:

MR. BRUCE LATIMER 145 Jermyn Street, W.

Scribbled across the top in pencil were the following words:

“Thanks. I shall be still more grateful if you will look me up at the above address.”

Quickly and unobtrusively I tucked it away in my waistcoat pocket, and glancing at the total of the bill, which came to about fifteen shillings, put down a couple of my few remaining sovereigns. It pays to be a little extravagant when you have been well served.

A swift inspection of the mirror showed me that neither of the occupants of the end table was looking in my direction, so taking my chance I rose quickly to my feet and stepped forward behind the shelter of the nearest pillar. Here I was met by another waiter who handed me my hat and stick, while his impassive colleague, pocketing the two pounds, advanced to the door and opened it before me with a polite bow. I felt rather like the hero of a melodrama making his exit after the big scene.

Once in the street, the full realization of what I had just been through came to me with a sort of curious shock. It seemed an almost incredible thing that a man should make an attempt to drug or poison another in a public restaurant, but, unless I was going off my head, that was what had actually occurred. Of course I might possibly have been mistaken in what I saw in the glass, but the readiness with which Mr. Latimer (somehow the name seemed vaguely familiar to me) had accepted my hint rather knocked that theory on the head. It showed that he, at all events, had not regarded such a contingency as being the least bit incredible.

I began to try and puzzle out in my mind what bearings this amazing incident could have on my own affairs. I was not even sure as yet whether the man with the scar had been really spying on my movements or whether my seeing him twice on the night of my arrival in Town had been purely a matter of coincidence. If he was a friend of McMurtrie’s, it seemed to stand to reason that’ Mr. Bruce Latimer was not. Even in such a weird sort of syndicate as I had apparently stumbled against it was hardly probable that the directors would attempt to poison each other in West End restaurants.

The question was should I accept the invitation pencilled across the card? I was anxious enough in all conscience to find out something definite about McMurtrie and his friends, but I certainly had no wish to mix myself up with any mysterious business in which I was not quite sure that they were concerned. For the time being my own affairs provided me with all the interest and excitement that I needed. Besides, even if the man with the scar was one of the gang, and had really tried to poison or drug his companion, I was scarcely in a position to offer the latter my assistance. Apart altogether from the fact that I had given my promise to the doctor, it was obviously impossible for me to explain to a complete stranger how I came to be mixed up with the matter. An escaped convict, however excellent his intentions may be, is bound to be rather handicapped in his choice of action.

With my mind busy over these problems I pursued my way home, only stopping at a small pub opposite Victoria to buy myself a syphon of soda and a bottle of drinkable whisky. With these under my arm (it’s extraordinary how penal servitude relieves one of any false pride) I continued my journey, reaching the house just as Big Ben was booming out the stroke of half-past nine.

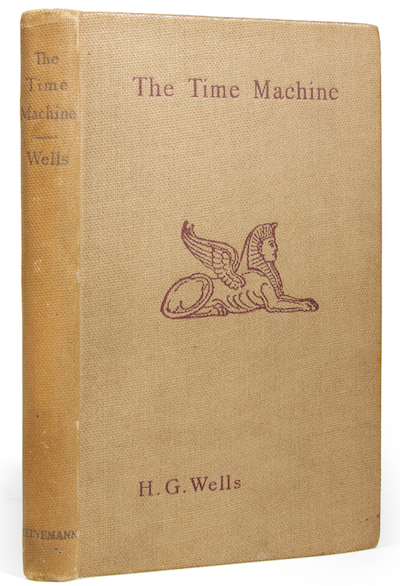

It seemed a bit early to turn in, but I had had such a varied and emotional day that the prospect of a good night’s rest rather appealed to me. So, after mixing myself a stiff peg, I undressed and got into bed, soothing my harassed mind with another chapter or two of H.G. Wells before attempting to go to sleep. So successful was this prescription that when I did drop off it was into a deep, dreamless slumber which was only broken by the appearance of Gertie ‘Uggins with a cup of tea at eight o’clock the next morning.

Soundly and long as I had slept I didn’t hurry about getting up. According to Joyce, Tommy would not be back until somewhere about two, and I had had so many grisly mornings of turning out at five o’clock after a night of sleepless horror that the mere fact of being able to lie in bed between clean sheets was still something of a novelty and a pleasure. Lie in bed I accordingly did, and, in the process of consuming several cigarettes, continued to ponder over the extraordinary events of the previous evening.

When I did roll out, it was to enjoy another nice hot bath and an excellent breakfast. After that I occupied myself for some time by running over the various notes and calculations which I had made while I was with McMurtrie, just in case I found it necessary to start the practical side of my work earlier than I expected. Everything seemed right, and savagely anxious as I was to stay in town till I could find some clue to the mystery of George’s treachery, I felt also an intense eagerness to get to grips with my new invention. I was positively hungry for a little work. The utter idleness, from any intelligent point of view, of my three years in prison, had been almost the hardest part of it to bear.

At about a quarter to two I left the house, and making my way down on to the embankment set off for Chelsea. It was a delightful day, warm and sunny as July; and this, combined with the fact that I was on my way to see Tommy, lifted me into a most cheerful frame of mind. Indeed I actually caught myself whistling—a habit which I don’t think I had indulged in since my eventful visit to Mr. Marks.

I looked up at George’s house as I passed, but except for a black cat sunning herself on the top of the gatepost there was no sign of life about the place. My thoughts went back to Joyce, and I wondered how the dinner party at the Savoy had gone off. I could almost see George sitting at one side of the table with that insufferable air of gallantry and self-satisfaction that he always assumed in the presence of a pretty girl. Poor, brave little Joyce! If the pluck and loyalty of one’s friends counted for anything, I was certainly as well off as any one in London.

As I drew near Florence Mansions I felt a sort of absurd inclination to chuckle out loud. Much as I disliked the thought of dragging Tommy into my tangled affairs, the prospect of springing such a gorgeous surprise on him filled me with a mischievous delight. Up till now, except for my arrest and sentence, I had never seen anything upset his superb self-possession in the slightest degree.

A glance at the board in the hall as I turned in showed me that he had arrived. I marched along the passage till I came to his flat, and lifting the knocker gave a couple of sharp raps. There was a short pause; then I heard the sound of footsteps, and a moment later Tommy himself opened the door.

He was wearing the same dressing-gown that I remembered three years ago, and at the sight of his untidy hair and his dear old badly-shaved face I as nearly as possible gave the show away. Pulling myself together with an effort, however, I made him a polite bow.

“Mr. Morrison?” I inquired in my best assumed voice.

“That’s me all right,” said Tommy.

“My name’s Nicholson,” I said. “I am an artist. I was asked to look you up by a friend of yours — Delacour of Paris.”

I had mentioned a man for whose work I knew Tommy entertained a profound respect.

“Oh, come in,” he cried, swinging open the door and gripping my hand; “come in, old chap. Delighted to see you. The place is in a hell of a mess, but you won’t mind that. I’ve only just got back from sailing.”

He dragged me into the studio, which was in the same state of picturesque confusion as when I had last seen it, and pulling up a large easy-chair thrust me down into its capacious depths.

“I’m awfully glad I was in,” he went on. “I wouldn’t have missed you for the world. How’s old Delacour? I haven’t seen him for ages. I never get over to Paris these days.”

“Delacour’s all right,” I answered—”at least, as far as I know.”

Tommy walked across the room to a corner cupboard. “You’ll have a drink, won’t you?” he asked; “there’s whisky and brandy, and Grand Marnier, and I’ve got a bottle of port somewhere if you’d care for a glass.”

There was a short pause. Then in my natural voice I remarked quietly and distinctly: “You were always a drunken old blackguard, Tommy.”

The effect was immense. For a moment Tommy remained perfectly still, his mouth open, his eyes almost starting out of his head. Then quite suddenly he sat down heavily on the couch, clutching a bottle of whisky in one hand and a tumbler in the other.

“Well, I’m damned!” he whispered.

“Never mind, Tommy,” I said cheerfully; “you’ll be in the very best society.”

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.