A Rogue By Compulsion (17)

By:

July 19, 2016

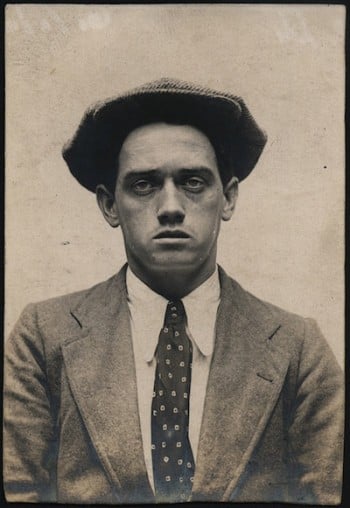

Victor Bridges’ 1915 hunted-man adventure, A Rogue by Compulsion: An Affair of the Secret Service, was one of the prolific British crime and fantasy writer’s first efforts. It was adapted, that same year, by director Harold M. Shaw as the silent thriller Mr. Lyndon at Liberty — the title under which the book was subsequently reissued. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize A Rogue by Compulsion — in 25 chapters — here at HILOBROW.

I gave Gertie her hat next morning when she brought me up my breakfast. It was a gorgeous thing — rather the shape of a dustman’s helmet, with a large scarlet bird nestling on one side of it, sheltered by some heavy undergrowth. Gertie’s face, as I pulled it out of the box, was a study in about eight different emotions.

“Oo—er,” she gasped faintly. “That ain’t never for me.”

“Yes, it is, Gertrude,” I said. “It was specially chosen for you by a lady of unimpeachable taste.”

I held it out to her, and she accepted it with shaking hands, like a newly-made peeress receiving her tiara.

“My Gawd,” she whispered reverently; “ain’t it just a dream!”

To be perfectly honest, it seemed to me more in the nature of a nightmare, but wild horses wouldn’t have dragged any such hostile criticism out of me.

“I think it will suit you very nicely, Gertie,” I said. “It’s got just that dash of colour which Edith Terrace wants.”

“Yer reely mean it?” she asked eagerly. “Yer reely think I’ll look orl right in it? ‘Course it do seem a bit funny like with this ‘ere frock, but I got a green velveteen wot belonged to Mrs. Oldbury’s niece. It won’t ‘alf go with that.”

“It won’t indeed,” I agreed heartily. Then, looking up from my eggs and bacon, I added: “By the way, Gertie, I’ve never thanked you for your letter. I had no idea you could, write so well.”

“Go on!” said Gertie doubtfully; “you’re gettin’ at me now.”

“No, I’m not,” I answered. “It was a very nice letter. It said just what you wanted to say and nothing more. That’s the whole art of good letter-writing.” Then a sudden idea struck me. “Look here, Gertie,” I went on, “will you undertake a little job for me if I explain it to you?”

She nodded. “Oo—rather. I’d do any think for you.”

“Well, it’s something I may want you to do for me after I’ve left.”

Her face fell. “You ain’t goin’ away from ‘ere — not for good?”

“Not entirely for good,” I said. “I hope to do a certain amount of harm to at least one person before I come back.” I paused. “It’s just possible,” I continued, “that after I’ve gone somebody may come to the house and ask questions about me — how I spent my time while I was here, and that sort of thing. If they should happen to ask you, I want you to tell them that I used to stay in bed most of the day and go to the theatre in the evening. Do you mind telling a lie for me?”

Gertie looked at me in obvious amazement. “I don’t think,” she observed. “Wotjer taike me for — a Sunday-school teacher?”

“No, Gertie,” I said gravely; “no girl with your taste in hats could possibly be a Sunday-school teacher.” Then pushing away my plate and lighting a cigarette, I added: “I’ll leave you a stamped addressed envelope and a telegraph form. You can send me the wire first to say if any one has called, and then write me a line afterwards by post telling me what they were like and what they said.”

“I can do that orl right,” she answered eagerly. “If they talks to

Mrs. Oldbury I’ll listen at the keyhole.”

I nodded. “It’s a practice that the best moralists condemn,” I said, “but after all, the recording angel does it.” Then getting up from the table, I added: “You might tell Mrs. Oldbury I should like to see her.”

When that good lady arrived I acquainted her with the fact that I intended to leave her house in about two hours’ time. Any resentment which she might have felt over this slightly abrupt departure was promptly smoothed away by my offer to take on the rooms for at least another fortnight. I did this partly with the object of leaving a pleasant impression behind me, and partly because I had a vague idea that it might come in handy to have some sort of headquarters in London where I was known and recognized as Mr. James Nicholson.

Having settled up this piece of business I sat down and wrote to McMurtrie. It was a task which required a certain amount of care and delicacy, but after two trial essays I succeeded in turning out the following letter, which seemed to me about to meet the situation.

“DEAR DR. McMURTRIE:

“As you have probably heard, I received your letter yesterday, and I am making arrangements to go down to Tilbury tomorrow by the 11.45.

“Of course in a way I am sorry to leave London—it’s extraordinary what a capacity for pleasure a prolonged residence in the country gives one—but at the same time I quite agree with you that business must come first.

“I shall start work directly I get down, and if all the things I asked for in my list have been provided, I don’t think it will be long before I have some satisfactory news for you. Unless I see you or hear from you before then I will write to the Hotel Russell directly there is anything definite to communicate.

“Meanwhile please give my kind regards to your amiable friend and colleague, and also remember me to his charming daughter.

“Believe me,

“Yours sincerely,

“JAMES NICHOLSON.”

With its combined touch of seriousness and flippancy, this appeared to me exactly the sort of letter that McMurtrie would expect me to write. I couldn’t resist putting in the bit about his “amiable” friend, for the recollection of Savaroff’s manner towards me still rankled gently in my memory. Besides I had a notion it would rather amuse McMurtrie, whose more artistic mind must have been frequently distressed by his colleague’s blustering surliness.

I could think of nothing else which required my immediate attention, so going into my bedroom I proceeded to pack up my belongings. I put in everything I possessed with the exception of Savaroff’s discarded garments, for although I was keeping on the rooms I had no very robust faith in my prospects of ever returning to them. Then, ringing the bell, I despatched Gertrude to fetch me a taxi, while I settled up my bill with Mrs. Oldbury.

“An’ seem’ you’ve taken on the rooms, sir,” observed that lady, “I ‘opes it’s to be a case of ‘say orrivar an’ not good-bye.'”

“I hope it is, Mrs. Oldbury,” I replied. “I shall come back if I possibly can, but one never knows what may happen in life.”

She shook her head sombrely. “Ah, you’re right there, sir. An’ curious enough that’s the very identical remark my late ‘usband was ser fond o’ makin’. I remember ‘is sayin’ it to me the very night before ‘e was knocked down by a bus. Knocked down in Westminister ‘e was, and runned over the body by both ‘ind wheels. ‘E never got over it — not as you might say reely got over it. If ever ‘e ate cheese after that it always give ‘im a pain in ‘is stomick.”

An apropos remark about “come wheel come woe” flashed into my mind, but before I could frame it in properly sympathetic language, a taxi drew up at the door with Gertie ‘Uggins installed in state alongside the driver.

Both she and Mrs. Oldbury stood on the step, and waved farewell to me as I drove down the street. I was quite sorry to leave them. I felt that they both liked me in their respective ways, and my present list of amiably disposed acquaintances was so small that I objected to curtailing it by the most humble member.

All the way to Tilbury I occupied myself with the hackneyed but engrossing pursuit of pondering over my affairs. Apart from my own private interest in the matter, which after all was a fairly poignant one, the mysterious adventure in which I was involved filled me with a profound curiosity. Latimer’s dramatic re-entry on to the scene had thrown an even more sinister complexion over the whole business than it boasted before, and, like a man struggling with a jig-saw problem, I tried vainly to fit together the various pieces into some sort of possible solution.

I was still engaged in this interesting occupation when the train ran into Tilbury station. Without waiting for a porter I collected my various belongings, and stepped out on to the platform.

McMurtrie had told me in his letter that he would arrange for some one to meet me; and looking round I caught sight of a burly red-faced gentleman in a tight jacket and a battered straw hat, sullenly eyeing the various passengers who had alighted. I walked straight up to him.

“Are you waiting for me — Mr. James Nicholson?” I asked.

He looked me up and down in a kind of familiar fashion that distinctly failed to appeal to me.

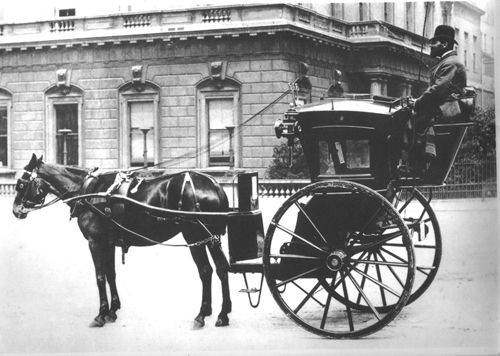

“That’s right,” he said. Then as a sort of afterthought he added, “I gotter trap outside.”

“Have you?” I said. “I’ve got a couple of bags inside, so you’d better come and catch hold of one of them.”

His unpleasantly red face grew even redder, and for a moment he seemed to meditate some spirited answer. Then apparently he thought better of it, and slouching after me up the platform, possessed himself of the larger and heavier of my two bags, which I had carefully left for him.

The trap proved to be a ramshackle affair with an ill-kept but powerful-looking horse between the shafts. I climbed up, and as I took my seat I observed to my companion that I wished first of all to call at the post-office.

“I dunno nothin’ ’bout that,” he grunted, flicking his whip. “My orders was to drive you to Warren’s Copse.”

“I don’t care in the least what your orders were,” I answered. “You can either go to the post-office or else you can go to the Devil. There are plenty of other traps in Tilbury.”

He was evidently unused to this crisp style of dialogue, for after glaring at me for a moment in a sort of apoplectic amazement he jerked his horse round and proceeded slowly down the street.

“’Ave it yer own way,” he muttered.

“I intend to,” I said cheerfully.

We pulled up at the post-office, a large red-brick building in the main street, and leaving my disgruntled friend sitting in the trap, I jumped out and pushed open the swing door. Except for an intelligent-looking clerk behind the counter the place was empty.

“Good-morning,” I said. “I wonder if you could help me out of a slight difficulty about my letters?”

“What sort of a difficulty?” he inquired civilly.

“Well, for the next week or two,” I said, “I shall be living in a little hut on the marshes about two miles to the east from here, and quite close to the sea-wall. I am making a few chemical experiments in connection with photography” (a most useful lie this), “and I’ve told my friends to write or send telegrams here — to the post-office. I wondered, if anything should come for me, whether you had a special messenger or any one who could bring it over. I would be delighted to pay him his proper fee and give him something extra for his trouble. My name is Nicholson — Mr. James Nicholson.”

The man hesitated for a moment. “I don’t think there will be any difficulty about that — not if you leave written instructions. I shall have to ask the postmaster when he comes in, but I’m pretty certain it will be all right.”

I thanked him, and after writing out exactly what I wanted done, I returned to my friend in the trap, who, to judge from his expression, did not appear to have benefited appreciably from my little lesson in patience and politeness. Under the circumstances I decided to extend it.

“I am going across the street to get some things I want,” I observed. “You can wait here.”

He made an unpleasant sound in his throat, which I think he intended for an ironical laugh. “Wot you want’s a bus,” he remarked; “a bus an’ a bell an’ a ruddy conductor.”

I came quite close and looked up into his face, smiling. “What you want,” I said quietly, “is a damned good thrashing, and if I have any more of your insolence I’ll pull you down out of the trap and give you one.”

I think something in my voice must have told him I was speaking the literal truth, for although his mouth opened convulsively it closed again without any audible response.

I strolled serenely across the road to where I saw an “Off-Licence.” I had acted in an indiscreet fashion, but whatever happened I was determined to put up with no further rudeness from anybody. I had had all the discourtesy I required during my three years in Princetown.

My purchases at the Off-Licence consisted of three bottles of whisky and two more of some rather obscure brand of champagne. It was possible, of course, that McMurtrie’s ideas of catering included such luxuries, but there seemed no reason for running any unnecessary risk. As a prospective host it was clearly my duty to take every reasonable precaution.

Armed with my spoils I returned to the trap, and stored them away carefully beneath the seat. Then I climbed up alongside the driver.

“Now you can go to Warren’s Copse,” I said; and without making any reply the tomato-faced gentleman jerked round his horse’s head, and back we went up the street.

I can’t say it was exactly an hilarious drive. I felt cheerful enough myself, but my companion maintained a depressed and lowering silence, broken only by an occasional inward grunt, or a muttered curse at the horse. It struck me as curious and not a little sinister that McMurtrie should be employing such an uncouth ruffian, but I supposed that he had some sound reason for his choice. I couldn’t imagine McMurtrie doing anything without a fairly sound reason.

Within about ten minutes of leaving the town, we came out on to the main road that bounded the landward side of the marshes. I caught sight of my future home looking very small and desolate against the long stretch of sea-wall, and far in the distance I could just discern the mast of the Betty still tapering up above the bank of the creek. It was comforting to know that so far at all events Mr. Gow had neither sunk her nor pawned her.

Warren’s Copse proved to be the small clump of trees that I had noticed on the previous day, and my driver pulled up there and jerked the butt of his whip in the direction of the hut.

“There y’are,” he said. “We can’t get no nearer than this.”

There was a good distance to walk across the marsh, and for a moment I wondered whether to insist upon his getting out and carrying one of my bags, I decided, however, that I had had quite enough of the surly brute’s company, so jumping down, I took out my belongings, and told him that he was at liberty to depart.

He drove off without a word, but he had not gone more than about thirty yards when he suddenly turned in his seat and called out a parting observation.

“I ain’t afraid o’ you— you — ‘ulkin’ bully!” he shouted; “an’ don’t you think it neither.”

Then, whipping up the horse, he broke into a smart canter, and disappeared round a bend in the road.

When I had done laughing, I shoved a bottle into each side pocket, and stowed away the other three in the emptier of my two bags. The latter were no light weight to lug along, and by the time I had covered the half-mile of marsh that separated me from the hut I had come to the conclusion that the profession of a railway porter was one that I should never adopt as a private hobby.

As soon as I unlocked the door, I saw that I had not been far wrong in my guess about a caretaker on the previous afternoon. Some one, at all events, had been there in the interval, for the pile of cooking and eating utensils were now arranged on a rough shelf at the back, while the box which I had noticed had been unpacked and its contents set out on the kitchen table.

I glanced over them with some interest. There were packets of tea and sugar, several loaves of bread, and a number of gaily-coloured tins, containing such luxuries as corned beef, condensed milk, tongue, potted meat, and golden syrup. Except for the tea, however, there seemed to be a regrettable dearth of liquid refreshments, and I mentally thanked Providence for my happy inspiration with regard to the Off-Licence.

I pottered about a bit, unpacking my own belongings, and putting things straight generally. As I seemed likely to be spending some time in the place, I thought I might as well make everything as comfortable and tidy as possible to start with; and, thanks to my combined experience of small boats and prison cells, I flatter myself I made rather a good job of it.

By the time I had finished I was feeling distinctly hungry. I opened one of the tongues, and with the additional aid of bread and whisky made a simple but satisfying lunch. Then I sat down on the bed and treated myself to a pipe before going across to the shed to start work. Smoking in business hours is one of those agreeable luxuries which an inventor of high explosives finds it healthier to deny himself.

I could see no sign of any one about when I went outside. Except for a few gulls, which were wheeling backwards and forwards over the sea-wall, I seemed to have the whole stretch of marsh and saltings entirely to myself. Some people, I suppose, would have found the prospect a depressing one, but I was very far from sharing any such opinion. I like marsh scenery, and for the present at all events I was fully able to appreciate the charms which sages of all times are reported to have discovered in solitude.

I shall never forget the feeling of satisfaction with which I closed the door of the shed behind me and looked round its clean, well-lighted interior. A careful examination soon showed me that McMurtrie’s share in the work had been done as thoroughly and conscientiously as I had imagined from my brief inspection on the previous day. Everything I had asked for was lying there in readiness, and, much as I disliked and mistrusted the doctor, it was not without a genuine sensation of gratitude that I hung up my coat and proceeded to set to work.

Briefly speaking, my new discovery was an improvement on the famous C. powder, invented by Lemartre. It was derived from the aromatic series of nitrates (which that great scientist always insisted to be the correct basis for stable and powerful explosives), but it owed its enormously increased force to a fresh constituent, the introduction of which was entirely my own idea. I had been working at it for about nine months before my arrest, and after several disappointing failures I had just succeeded in achieving what I believed to be my object, when my experiments had been so unkindly interrupted.

Still, all that remained now was comparatively clear sailing. I had merely to follow out my former process, and I had taken care to order the various ingredients in as fully prepared a state as possible for immediate use. I had also taken care to include one or two other articles, which as a matter of fact had nothing on earth to do with the business in hand. It was just as well, I felt, to obscure matters a trifle, in case any inquiring mind might attempt to investigate my secret.

For hour after hour I worked on, sorting out my various chemicals, and preparing such methods of treatment as were necessary in each case. I was so interested in my task that I paid no attention at all to the time, until with something of a shock I suddenly realized that the light was beginning to fail. Looking at my watch I found that it was nearly half-past seven.

There was still a certain amount to do before I could knock off, so, stopping for a moment to mix myself a well-earned whisky-and-water, I switched on the two electric head-lights which McMurtrie had provided as a means of illumination. With the aid of these I continued my labours for perhaps another hour and a half, at the end of which time I began to feel that a little rest and refreshment would be an agreeable variation in the programme.

After making sure that everything was safe, I turned out the lights, and locking up the door, walked back to the hut. I was just entering, when it suddenly struck me that instead of dining in solitary state off tongue and bread, I might just as well stroll over to the Betty and take my evening repast in the engaging company of Mr. Gow.

No sooner had this excellent idea entered my head than I decided to put it into practice. The moon was out, and there appeared to be enough light to see my way by the old route along the river shore, so, walking down to the sea-wall, I climbed over, and set off in the direction of the creek.

It was tricky sort of work, with fine possibilities of spraining one’s ankle about it, but by dint of “going delicately,” like Agag, I managed to reach the end of my journey without disaster. As I rounded the bend I saw the Betty lying out in mid-stream, bathed in a most becoming flood of moonlight. A closer observation showed me the head and shoulders of Mr. Gow protruding from the fo’c’s’le hatch.

He responded to my hail by scrambling up on deck and lowering himself into the dinghy, which with a few vigorous jerks he brought to the shore.

“I’ve come to have supper with you, Mr. Gow,” I observed. “Have you got anything to eat?”

He touched his cap and nodded. “I says to meself it must be you, sir, d’rectly I heard you comin’ round the crick. There ain’t much comp’ny ’bout here at night-time.”

“Nor in the daytime either,” I added, pushing the boat off from the bank.

“And that’s a fact, sir,” he remarked, settling down to the oars. “There was one gent round here this morning askin’ his way, but except for him we bin remarkable quiet.”

“What sort of a gent?” I demanded with interest.

“Smallish, ‘e was, sir, an’ very civil spoken. Wanted to get to Tilbury.”

“Did he ask who the boat belonged to, by any chance?”

Mr. Gow reflected for a moment. “Now you come to mention it, sir, I b’lieve ‘e did. Not as I should have told ‘im anything, even if I’d known. I don’t hold with answerin’ questions.”

“You’re quite right, Mr. Gow,” I observed, catching hold of the stern of the Betty. “It’s a habit that gets people into a lot of trouble — especially in the Law Courts.”

We clambered on board, and while my companion made the dinghy fast, I went down into the cabin, and proceeded to rout out the lockers in search of provisions. I discovered a slab of pressed beef, and some rather stale bread and cheese, which I set out on the table, wondering to myself, as I did so, whether the inquisitive stranger of the morning was in any way connected with my affairs. It couldn’t have been Latimer, for that gentleman was very far from being “smallish,” a remark which applied equally well to our mutual friend with the scar. I was still pondering over the question when I heard Mr. Gow drop down into the fo’c’s’le, and summond him through the connecting door to come and join the feast.

He accepted my invitation with some embarrassment, as became a “paid hand,” but a bottle of Bass soon put him at his ease. We began by discussing various nautical topics, such as the relative merits of a centre-board or a keel for small boats, and whether whisky or beer was really the better drink when one was tired and wet through. It was not until we had finished our meal and were sitting outside enjoying our pipes that I broached the question that was at the back of my mind.

“Look here, Gow,” I said abruptly, “were you speaking seriously when you suggested that launch ran you down on purpose?”

His face darkened, and then a curious look of slow cunning stole into it.

“Mebbe they did, and mebbe they didn’t,” he answered. “Anyway, I reckon they wouldn’t have bin altogether sorry to see me at the bottom o’ the river.”

“But why?” I persisted. “What on earth have you been doing to them?”

Mr. Gow was silent for a moment. “‘Tis like this, sir,” he said at last. “Bein’ about the river all times o’ the day an’ night, I see things as other people misses — things as per’aps it ain’t too healthy to see.”

“Well, what have you seen our pals doing?” I inquired.

“I don’t say I seen ’em doin’ nothin’ — nothin’ against the law, so to speak.” He looked round cautiously. “All the same, sir,” he added, lowering his voice, “it’s my belief as they ain’t livin’ up there on Sheppey for no good purpose. Artists they calls ’emselves, but to my way o’ thinking they’re a sight more interested in forts an’ ships an’ suchlike than they are in pickchers and paintin’.”

I looked at him steadily for a moment. There was no doubt that the man was in earnest.

“You think they’re spies?” I said quietly.

He nodded his head. “That’s it, sir. Spies — that’s what they are; a couple o’ dirty Dutch spies — damn ’em.”

“Why don’t you tell the police or the naval people?” I asked.

He laughed grimly. “They’d pay a lot of heed to the likes o’ me, wouldn’t they? You can lay them two fellers have got it all squared up fine and proper. Come to look into it, an’ you’d find they was artists right enough; no, there wouldn’t be no doubt about that. As like as not I’d get two years ‘ard for perjurin’ and blackmail.”

To a certain extent I was in a position to sympathize with this point of view.

“Well, we must keep an eye on them ourselves,” I said, “that’s all. We can’t have German spies running up and down the Thames as if they owned the blessed place.” I got up and knocked out my pipe. “The first thing to do,” I added, “is to summons them for sinking your boat. If they are spies, they’ll pay up without a murmur, especially if they really tried to do it on purpose.”

Mr. Gow nodded his head again, with a kind of vicious obstinacy. “They done it a-purpose all right,” he repeated. “They seen me watching of ’em, and they knows that dead men tell no tales.”

There scarcely seemed to me to be enough evidence for the certainty with which he cherished this opinion; but the mere possibility of its being a fact was sufficiently disturbing. Goodness knows, I didn’t want to mix myself up in any further troubles, and yet, if these men were really German spies, and, in addition to that, sufficiently desperate to attempt a cold-blooded murder in order to cover up their traces, I had apparently let myself in for it with a vengeance.

Of course, if I liked, I could abandon Mr. Gow to pursue his claim without any assistance; but that was a solution which somehow or other failed to appeal to me. In a sense he had become my retainer; and we Lyndons are not given to deserting our retainers under any circumstances. At least, I shouldn’t exactly have liked to face my father in another world with this particular weakness against my record.

Altogether it was in a far from serene state of mind that I climbed down into the dinghy, and allowed Mr. Gow to row me back to the bank.

“Will you be over tomorrow, sir?” he asked, as he stood up in the boat ready to push off.

“I don’t think so, I shall be rather busy the next two or three days.” Then I paused a moment. “Keep your eyes open generally, Mr. Gow,” I added; “and if any more gentlemen who have lost their way to Tilbury come and ask you the name of the Betty‘s owner, tell them she belongs to the Bishop of London.”

He touched his cap quite gravely. “Yessir,” he said. “Good-night, sir.”

“Good-night, Mr. Gow,” I replied, and scrambling up the bank, I set off on my return journey.

READ GORGEOUS PAPERBACKS: HiLoBooks has reissued the following 10 obscure but amazing Radium Age science fiction novels in beautiful print editions: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”), Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt, H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook, Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins, William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land, J.D. Beresford’s Goslings, E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man, Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage, and Muriel Jaeger’s The Man with Six Senses. For more information, visit the HiLoBooks homepage.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague | Rudyard Kipling’s With the Night Mail (and “As Easy as A.B.C.”) | Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt | H. Rider Haggard’s When the World Shook | Edward Shanks’ The People of the Ruins | William Hope Hodgson’s The Night Land | J.D. Beresford’s Goslings | E.V. Odle’s The Clockwork Man | Cicely Hamilton’s Theodore Savage | Muriel Jaeger’s The Man With Six Senses | Jack London’s “The Red One” | Philip Francis Nowlan’s Armageddon 2419 A.D. | Homer Eon Flint’s The Devolutionist | W.E.B. DuBois’s “The Comet” | Edgar Rice Burroughs’s The Moon Men | Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland | Sax Rohmer’s “The Zayat Kiss” | Eimar O’Duffy’s King Goshawk and the Birds | Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Lost Prince | Morley Roberts’s The Fugitives | Helen MacInnes’s The Unconquerable | Geoffrey Household’s Watcher in the Shadows | William Haggard’s The High Wire | Hammond Innes’s Air Bridge | James Branch Cabell’s Jurgen | John Buchan’s “No Man’s Land” | John Russell’s “The Fourth Man” | E.M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” | John Buchan’s Huntingtower | Arthur Conan Doyle’s When the World Screamed | Victor Bridges’ A Rogue By Compulsion | Jack London’s The Iron Heel | H. De Vere Stacpoole’s The Man Who Lost Himself | P.G. Wodehouse’s Leave It to Psmith | Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game” | Houdini and Lovecraft’s “Imprisoned with the Pharaohs” | Arthur Conan Doyle’s “The Sussex Vampire”.