Unseen Cinema: The Exiles

By:

February 2, 2012

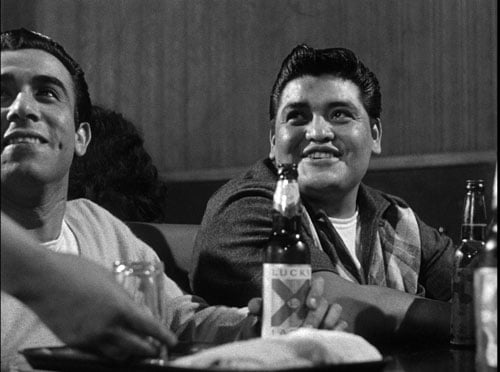

The Exiles, dir. Kent Mackenzie, 1961.

An aching, lost love letter from the margins of a Los Angeles past, Kent Mackenzie’s The Exiles (1961) is a semi-documentary look at the lives of a group of Indians living in Los Angeles’ gritty Bunker Hill neighborhood. Shot on a zero budget over a three-year period from 1958 to 1961, Mackenzie’s scrappy verité tone poem works off a narrative constructed from recorded interviews with the Indians. He filmed them playing themselves and improvising scenes, and then assembled a story that followed a single night in their lives.

Though half a century old, the film wasn’t given its first official theatrical release until 2008, thanks to Milestone films, along with presenters Charles Burnett and Sherman Alexie.

At the emotional core of The Exiles are the pregnant, neglected Yvonne (Yvonne Williams) and her husband Homer (Homer Nish). The film tracks the young couple and their friends’ listless drinking, poker playing and nighttime ramblings through Bunker Hill. But the film’s deep resonance comes from Mackenzie’s choice to marry voice-over of the characters’ internal monologues with the footage. As their bodies wander through the night, seeking pleasure and distraction, we listen to their secret hopes, dreams and fears. The convergence of these intimate voices with the pristine black and white 16mm images are sublime.

In one of the most moving sequences, Yvonne walks aimlessly through downtown’s Grand Central Market, under a hard fluorescent glare, past food display cases and clothing mannequins. We hear her thoughts: “I always wanted to go… get away from my people… and go somewhere… where somebody will make me feel different…” and later: “I used to pray every night before I went to bed and asked for something that I wanted, and I never got it, or it seems like my prayers were never answered. So I just gave up…”

It’s an unforgettable experience, watching these scenes of real people “acting” out stories from their waning culture, fifty years after the film’s creation. They are the echoes of a haunting, collective grief.

The performances are uniformly unaffected and authentic. And Mackenzie never comments on the action, he only allows it to unfold. We’re left to draw our own conclusions as to why these characters have drifted so far from their indigenous culture, to partying in seedy, downtown LA bars. If Mackenzie is making an argument, it’s that given their race and economic status, Yvonne and Homer have few other options.

The film’s artistry is, occasionally, not quite what one wants it to be. With five cinematographers and six editors, the framing and pacing varies in quality. But while the narrative occasionally drifts into dead ends, its very aimlessness reflects the character’s unspoken longings. And given that the standard Hollywood depiction of the Indian at that time was still very much the stock savage, The Exiles attention to its characters’ inner lives is positively radical.

Now, some fifty years later, the Bunker Hill neighborhood terrain of the film is unrecognizable. Occupied by tower condos, the Walt Disney Concert hall and valet parking lanes, there are few traces of its previous existence. The Exiles seems not just an artifact of a vanished culture, but one subsumed into a commodified illusion of the American dream. It’s a clear-eyed elegy for the lives of those long gone and never heard from.

Official site: http://www.exilesfilm.com/filmmaker.html

Read more from artist-in-residence Chris Rossi on HiLobrow.

HILOBROW’s Artist-in-residence archive.