Winds of Magic (7): Presidency of the Absurd

By:

October 25, 2009

The owl and the pussycat went to jail, for something the piggy-wig said.

They sat for a while with no hope of a trial, and paper bags over their heads,

Till a man with dark glasses belabored their asses. Puss went where the Bong Tree grows,

And the owl was put in a stress position and water was poured up his nose….

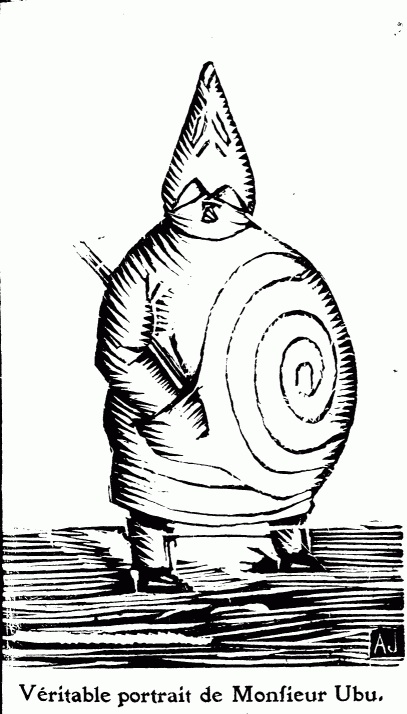

That’s the Bush era remix of “The Owl and the Pussycat.” Not quite right, is it? But not wrong either. In the literature of absurdity, torture is never far away. The baked, rolled, and smashed protagonists of Edward Lear’s limericks; Père Ubu’s Debraining Machine; the nightmare apparatus of Franz Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony”; Lucky on his leash in Waiting for Godot. When the goblins of the absurd are let loose, it seems to follow with biological inevitability that a man will become his brother’s torturer. Who’s to stop him? Morals are arbitrary, God’s in his grave, and space rings us like an iron perimeter. Nothing matters. Why not have a bit of fun?

History will have trouble digesting the irony of it — that George W. Bush, a man who claims Jesus as his favorite political philosopher and the Lord as his warrant, has presided over the transformation of US foreign policy into a God-destroying juggernaut of absurdity. “If you want to study the social and political history of modern nations,” wrote Thomas Merton in 1961, “study hell.” Merton was a Trappist monk, but he knew the world. In its relentless, chaotic sponsorship of torture, the Bush Administration has created many little chambers of hell, many places where reason is overthrown and sanctity denied. In such places — in Abu Ghraib, or Guantánamo, or Camp Cropper, or Bagram Air Base — human rights evaporate: there are no rights, no principles or precedents. There is only the despotism of the present tense, whose sole limit is the fact that you might die before it has exhausted its capacity for torment. It doesn’t get more absurd than that.

Edward Lear didn’t invent the limerick, but he might as well have. The form had existed for centuries before this shy Victorian landscape painter — tormented privately by epilepsy, which he called “my terrible demon” — made his name by turning it into a vehicle for violent irrationality:

There was a Young Person of Smyrna

Whose grandmother threatened to burn her;

But she seized on the cat, and said, “Granny, burn that!

You incongruous old woman of Smyrna!”

Lear was a post-Romantic who disliked getting carried away: he described his own mind as “concrete and abstemious,” and he knew that the key to successful nonsense (as he called his verse) lay in a crooked balancing of order and chaos. Without the punctilious containment of the limerick — its mirrored first and last lines creating a sense of psychotic circularity (literally, of loopiness) — his strange animalistic jokes would have had no punch line.

There was an old man who screamed out

Whenever they knocked him about;

So they took off his boots, and fed him with fruits,

And continued to knock him about.

Insisting that his nonsense was simple entertainment, written for the nursery, Lear was in fact one of the fathers of absurdity, of Kafka, Samuel Beckett, and Eugène Ionesco, unwilling herald of a universe “freed” — in the words of Martin Esslin, scholar of absurd theater — “from the shackles of logic,” where “wish-fulfillment will not be inhibited by considerations of human kindness.” The old man is fed with fruits to stop him screaming: once he’s quiet, the abuse can resume.

The Bush-era analogue to this situation would be the one in which the doctor stands by during the torture session, ensuring that the prisoner doesn’t die. During the course of one interrogation at the detention center in Guantánamo Bay, for example, as reported by Time magazine, prisoner 063 — Mohamed al-Qahtani, the so-called 20th hijacker of 9/11 — grew dangerously dehydrated. Medical corpsmen intervened, and al-Qahtani was pumped with three bags of saline. For the duration of the procedure, however, he remained strapped to his chair, and loud music (possibly Christina Aguilera, which had been used before) was played to keep him awake.

Nonsense is its own insurance. In the unhappy event that a prisoner expires before realizing his full potential as a source of intelligence, his corpse can be kept safely in the realm of meaninglessness — pickled, as it were, in absurdity. Steven H. Miles, in his 2005 book Oath Betrayed: Torture, Medical Complicity, and the War on Terror (Random House) describes the case of the detainee at Camp Cropper, near Baghdad International Airport, who was killed by a blow to the head. Two weeks later his body, complete with pre-prepared death certificate, was dropped at a local hospital. Cause of death: “sudden brainstem compression.” That unfortunate young man of Camp Cropper….

Michael Tucker and Petra Epperlein’s extraordinary documentary The Prisoner, or: How I Planned to Kill Tony Blair, which was released on DVD this past month, is a primer in the absurdity of the Iraq war. Elegant, soft-spoken Iraqi journalist Yunis Abbas falls victim to the process known as “cordon and capture” — in which US troops, acting sometimes on mere wisps of intelligence, round up suspects in nighttime sweeps — and is arrested at a wedding party. Somehow he and his brothers have been implicated in a bomb plot against visiting British Prime Minister Tony Blair, and, despite the fact that no bomb-making equipment is found at their house, they are taken into custody.

“They [terrorists] are very good about it,” explains US Lieutenant Colonel Bill Rabena, Commander of the 2/3 Field Artillery Capturing Unit. “They bring the material and they make the bomb there at the house, and then there’s basically not much material to find as evidence.” The cleaner and more harmless-looking the kitchen, in other words, the more likely it is that expert bomb makers have recently been at work in it.

This mania for culpability is pervasive. As soon as Yunis and his brothers arrive at the detention site at Camp Ganci, a subdivision of Abu Ghraib, they are enveloped in an almost Calvinist miasma of guilt: if you’re here, you must have done something. A female American interrogator spits in Yunis’s face and calls him a terrorist. When told of his starring role in a plot to kill Blair, Yunis laughs — one reaction to absurdity. The other is despair, which soon overwhelms him. (Del Rey has just published a novel called Harm, by veteran science-fiction author Brian Aldiss, on this exact theme.) “All is imaginary,” wrote Kafka in his diary in 1921. “Family, office, friends, the street, all imaginary, far away or close at hand, the woman; the truth that lies closest, however, is only this: that you are beating your head against the wall of a windowless and doorless cell.” (A year later, with no explanation, Yunis and his brothers are released.)

Another key document is Tony Lagouranis’s memoir Fear Up Harsh, just published by Penguin imprint NAL. Lagouranis was an Army interrogator with the US 513th Military Intelligence Brigade, and in 2004 he was sent to Iraq to participate in the ongoing intelligence-gathering operation at Abu Ghraib. The abuse scandal was already percolating, under military investigation, and would explode into the media inside four months — all Lagouranis knew was that “something bad” had happened on the nightshift over at the so-called Hard Site, and that it had been dealt with. The worst, then, might have been assumed to be over.

Not so. Fear Up Harsh is a painful and deeply moral account of the vitality of torture: its entropic ability, once the door has been opened to it, to shift, mutate, and intensify. Legalized abuse is a contagion: it begins with Alberto Gonzalez musing in a memo to the president that the Geneva Convention has been rendered “quaint” and “obsolete” by the new facts of war, and it ends with a prisoner’s body packed in ice. All this has been well-documented, but Lagouranis is the first to record in such diagnostic detail its effects on individual interrogators in the field — to provide us with a portrait, if you will, of the torturer as a young man.

Absurdity is staring him in the face: again and again he comes to the sickening conclusion that the men he is interrogating are innocent, or at least non-insurgent, but finds to his horror that he cannot extricate them from the system. The flawed logic of the interrogation program, by which coherent items of “actionable intelligence” are expected from men whose bodies and minds have been broken by torture, is inescapable. Admitting to a fellow soldier that he is feeling sorry for some of his more hapless cases, Lagouranis is mocked: “Can’t you see through these guys? They’re just trying to manipulate you.” Any pitiable human aspect displayed by a detainee is a result of training in sophisticated counter-interrogation techniques: the sorrier you feel, the harder you must work. The circularity is perfect, limerick-like, hellish. Lagouranis refers to this as his “problem with compassion.”

Nonetheless, within a few months he is a torturer. Transferred to Mosul, and frustrated at the intractability — the unbreakability — of a prisoner named Jafar, he confines him in a shipping container, bombards him with death metal and strobe lights, and puts dogs in his face until he wets himself. “These techniques,” writes Lagouranis, “were propagated throughout the Cold War, picked up again after 9/11, used by the CIA, filtered down to army interrogators at Guantánamo, filtered again through Abu Ghraib, and used, apparently, around the country by Special Forces. Probably someone in this chain was a real professional, and if torture works — which is debatable — maybe they had the training to make sure it worked. But at our end of the chain, we had no idea what we were doing.”

Days later, after a prisoner named Khalid has proved impervious to the dogs, the lights, the stress positions, and the sound — in this case, an audio version of Ben Stiller and Janeane Garofalo’s Feel This Book — Lagouranis is only mildly surprised to find himself with a single thought in his head: chop his fucking fingers off!

Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi opened and closed, triumphantly, on the same night in Paris in 1896. Jarry, described by one biographer as a “pistol-packing midget bicyclist,” was a maestro of shock. Having lit the fuse of boredom in his audience with a long pre-show harangue, he blew them up with his play’s dynamite first syllable: Merdre! This was his little twist, his touch of reverb, on the word merde, which is, of course, French for “shit”: I have seen it translated as “shittr,” “pshit,” and (my favorite) “shitski!” In any event, it caused a riot, the performance was over, and Père Ubu, Jarry’s potty-mouthed and tyrannical anti-hero, passed immediately into legend.

Ubu is greedy, sloppy, querulous, power-mad, imbecilic, nonsensical: his governing urge is to be king of Poland (“that is to say, Nowhere,” as Jarry explained in his introduction), to which end he conspires and slaughters with Rabelaisian glee. “Into the trap!” he howls, tossing noblemen, financiers, and the chief of police through a trapdoor and into the “sub-cellars” of his Debraining Machine.

There is nothing symbolic about him — his ludicrous carnality defies all symbolism. And yet he contrives to represent both Nature and Man in an absurd world. Writing in the literary magazine Horizon, in 1945, Cyril Connolly hailed Ubu as “the Santa Claus of the Atomic Age”: we might better understand him as a sort of reviled grandfather to Raw Power–era Iggy Pop.

Ubu Roi, the play, has dated. Read today, it has the rude and jittery eccentricity of a vintage stag film. But Ubu himself is more with us than ever. The Abu Ghraib photos, with their obscene raptures, their drunken, sadistic pride, and above all their demented aesthetic sense, are a gallery of Ubu-isms. Tony Lagouranis was in the grip of Ubu when it occurred to him to amputate Khalid’s fingers, as were those torturers who, for the benefit of their Islamic captives, desecrated the Koran with a truly Surrealist gusto. (Newsweek was forced to retract its 2005 story about the use of this technique at Guantánamo Bay, but plenty of other credible accusations are outstanding.)

The prophets of the absurd saw all of this coming. As the Bush era collapses into ignominy, we find ourselves somewhat in the position of the explorer in Kafka’s “In the Penal Colony,” watching in a kind of dissociated abhorrence as a Gonzalez-style flunky tightens the screws for one last ride on the torture machine: “Have you ever heard of our former Commandant? No? Well, it isn’t saying too much if I tell you that the organization of the whole penal colony is his work.”

And if Gonzalez, in all the blandness of his fanaticism, can be found in Kafka, then those two beasts Dick Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld can be found in Ionesco — in his play Rhinoceros, where humans are changing one by one into brutal, hard-charging pachyderms. “Moral standards!” bellows one such man/rhino, as his hide thickens and the beginnings of a horn bulge out of his forehead, “I’m sick of moral standards! We need to go beyond moral standards!” Chop his fucking fingers off.

As for the rest of us, faced with this inconvenient problem, we seem to have learned well the lesson enacted by Père Ubu in Jarry’s sequel, Ubu Cocu: take your conscience out of its suitcase, consult it briefly and then flush it — like the Koran — down the toilet.

Originally published by The Boston Globe’s Ideas section on Sept. 11, 2005. From 2003-08, our friend and colleague James Parker, currently a contributing editor at The Atlantic, was a culture critic for the Boston Globe’s Ideas section and for Boston’s alt-weekly, The Phoenix. HiLobrow.com has curated a collection of Parker’s writings from this period. This installment is the seventh in a series of ten.