John Coltrane

By:

September 23, 2009

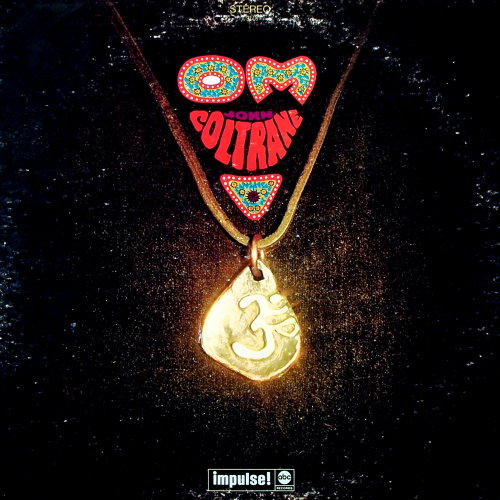

Until 1964, JOHN COLTRANE (1926-67) was a virtuoso, blasting out bebop as wing-man to the likes of Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk, and later leading his own hard bop lineups, where he is probably most famous for deconstructing sugar-coated classics like “My Favorite Things” and “Chim Chim Cher-ee.” But beginning with Ascension in ’65, and continuing with Om, Meditations, and other exploratory albums, Coltrane stretched out his arms and, bathed in a heavenly glow, launched himself upwards in search of a different plane, one where music could be the “whole expression of one’s being.” He left many jazz fans behind, but this metaphysical act made him so much more than a great saxophonist and composer. In the frenetic mash of these recordings, against a primal rumble of bass and drums and a mid-register wall of piano (and whatever other instruments may have been ushered into the studio), his saxophone becomes the Coltranograph — a precision piece of medical apparatus that charts, in painful detail, the real-time emotional and spiritual state of Coltrane’s heart and head. Listening to the impossible runs and unpredictable chord sequences, the spine-chilling screeches and winsome wails, the punctuation of pause and breath, you begin to believe in something, anything, that exists beyond the real.

Each day, HILOBROW pays tribute to one of our favorite high-, low-, no-, or hilobrow heroes on that person’s birthday.

READ MORE about the Postmodernist Generation (1924-33).

READ MORE HiLo Hero shout-outs.

SUBSCRIBE to HiLo Hero updates via Facebook.

SHARE this post, by clicking on the toolbar below.