SEMIOPUNK (33)

By:

May 1, 2025

An irregular, ongoing series of posts dedicated to surfacing examples (and predecessors) of the sf subgenre that HILOBROW was the first to name “semiopunk.”

BABEL (2022) | BABEL-17 (1966) | CAMP CONCENTRATION (1968) | A CANTICLE FOR LEIBOWITZ (1959) | CAT’S CRADLE (1963) | COSMONAUT KEEP (2000) | THE DIFFERENT GIRL (2013) | DOOM PATROL (1987–91) | THE EINSTEIN INTERSECTION (1967) | EMBASSYTOWN (2011) | ENGINE SUMMER (1979) | EXPLOITS AND OPINIONS OF DR. FAUSTROLL, PATAPHYSICIAN (1911) | FEERSUM ENDJINN (1994) | FLATLAND (1884) | FRIDAY (1982) | LE GARAGE HERMÉTIQUE (1976–79) | THE GLASS BEAD GAME (1943) | GLASSHOUSE (2006) | GRAVITY’S RAINBOW (1973) | THE HAMPDENSHIRE WONDER (1911) | LORD OF LIGHT (1967) | THE MAN WITH SIX SENSES (1927) | THE MOUNTAIN IN THE SEA (2022) | NINEFOX GAMBIT (2016) | ODD JOHN (1935) | PATTERN RECOGNITION (2003) | THE PLAYER OF GAMES (1988) | RIDDLEY WALKER (1980) | RODERICK (1980–83) | SNOW CRASH (1992) | THE SOFT MACHINE (1961) | SOLARIS (1961) | THE SPACE MERCHANTS (1953) | THE THREE STIGMATA OF PALMER ELDRITCH (1964) | TIME OUT OF JOINT (1959) | UBIK (1969) | VALIS (1981) | A VOYAGE TO ARCTURUS (1920) | VURT (1993) | WHITE NOISE (1985).

COSMONAUT KEEP

HILOBROW friend Deb Chachra got me stuck into Ken MacLeod’s terrific, loosely connected Fall Revolution series (The Star Fraction, The Stone Canal, The Cassini Division, The Sky Road); having devoured these, I was excited to start in on the author’s subsequent Engines of Light trilogy. Turns out that the series’ first installment, Cosmonaut Keep (2000), is not only an epic space opera and Charles Fort-style “blend of mocking humor, penetrating insight, and calculated outrageousness” (to quote UFOlogist Jerome Clark on Fort’s writings), but a work of semiopunk sf via which the reader will vicariously experience the thrill of pattern-discovery.

After a psychedelic preliminary section describing the sublime, utterly alien world of what we will eventually discover are something like colonies of bacteria (each of which consists of trillions of hyper-intelligent individuals bound together as a single entity, and dwelling throughout the galaxy in seemingly uninhabited comet nuclei and asteroids), we are introduced to Gregor Cairns and Elizabeth Harkness, young scientists cooperating on mapping the nervous system of the squid; specifically, they are analyzing “the peculiarities of cephalopod neural morphology.” Their collaborator and perhaps sponsor in this effort is Salasso, a humanoid whose smooth, grey skin, large, hairless head, and large, black, almond-shaped eyes are strongly reminiscent of a “Roswell Grey alien.” We are on the planet Mingulay, where humans are a somewhat inferior species.

Salasso is a “saur,” a species that was “lifted” (artificially evolved) from Earth’s dinosaur population during prehistoric times, by Architeuthys extraterrestris sapiens, which is to say a version of Earth’s giant squid species who’d themselves been “lifted” by yet another species — this one extraterrestrial. The kraken, as the evolved giant squid are known, are “the largest intelligent species, and almost certainly the largest intelligence, that humanity had ever encountered.” Thanks to the peculiar structure of their brains, the kraken are the only creatures capable of performing the calculations necessary for interstellar travel in a light-speed ship.

Mingulay, and other inhabited planets that revolve around Nova Sol in what is known as the “Second Sphere” (on the opposite side of the galaxy from humankind’s home planet), are visited regularly by the kraken-piloted ships. Human passengers who travel on these vessels are ferried to and from the planets’ surfaces by the saur… in disc-shaped “gravity skiffs.” Earth’s stories of alien abduction have their basis, it appears, in truth. In fact, the other planets in the Second Sphere are populated by the descendants of abducted humans, who for the past three thousand years have been building up an interplanetary civilization known as Nova Babylonia.

The human population of Mingulay, however, is an anomaly. They’ve showed up relatively recently, piloting a light-speed spaceship — from Earth — of their own design. Gregor is the direct descendant of the legendary “first navigator” of this cosmonaut crew. Over time, however, the secret of navigating among the stars has been lost. The research and analysis that Gregor and Elizabeth, aided and abetted by Salasso, are doing is part of a generations-long project to rediscover their ancestors’ ultra-complex navigation math.

There’s more going on, too: political maneuvering between Mingulay and the Nova Babylonia empire, a religious movement among the saurs, multiple love stories, and a cyberpunk-ish simultaneous back-story set on a mostly communist Earth in our not-distant-future. Here, however, I’ll just focus on the semiopunk aspect of Cosmonaut Keep.

There’s a bit of foreshadowing in the first pages of the book’s first chapter. Returning to harbor after fishing for squid to dissect, Gregor and Elizabeth and Salasso spot one of the kraken starship pilots swimming. Leaping out of the water playfully, “it glowed and flashed with flickering color.”

Deep-sea squid, as I was vaguely aware before reading this book, communicate in the dark by using bioluminescence and changing skin patterns. Photophores (light-producing organs) under their skin allow them to emit a yellow-green glow; and chromatophores (pigment cells) in their skin allow them to change color and create patterns. Researchers believe that the squid use a combination of these light and skin patterns to communicate complex messages, potentially similar to how humans use language.

By diagramming and annotating a squid’s nervous system, our human researchers hope to understand what another character calls the kraken’s “enormous, complicated brain, so different from our own.”

This character, Lydia, part of a trading family that travels on kraken ships, wonders whether “the cephalopod mode of communication via chromatophore display [is] something intrinsic to their neural anatomy? Does it vary within the species like human languages? Is it abstractly symbolic or is it fundamentally ideographic and quasi-pictorial?”

Now we’re talking…

Toggling back and forth between their marine biology research and his family’s surreptitious efforts to crack the code of light-speed travel, Gregor experiences a pattern-recognition revelation that will be familiar to my fellow semioticians: “It unfolded before his eyes, the map of the squid nervous system overlaying the data structures of the navigation problem. He understood the architecture of the mind that could understand the problem, and in so doing he understood it himself. He could see, in principle, how the problem could be solved.”

In conversation with his colleagues, Gregor announces: “‘What I’ve realized is that the actual solution to the [starship navigation] problem requires a non-human mind, specifically a squid mind, and that our research in cephalopod neurology can contribute to simulating such a mind — in its barest outlines, of course, but it’s the outline, the structure, the architecture, if you will, that counts.'” We latter-day structuralists get a big kick out of this sort of thing, of course. Though we cannot get beneath the surface things except by studying surface phenomena for immanent clues, our goal is always to catch a glimpse of the deep, hidden structure or architecture that shapes and guides surface phenomena.

Gregor will go on to muse: “‘I can see it all in my head, I can see how it would be done. The structure of the problem and the structure of the brain match so exactly it’s uncanny, it’s like they were made for each other.'”

This insight will lead to further speculations about the (utterly epic) plans of the bacteria-like “gods” when it comes to Earth’s krakens, saurs, and humans. Among the most powerful of the galaxy’s intelligences, we’ll learn, almost all of whom thrive everywhere except on planets’ surfaces, there are profound differences of opinion about how to deal with surface life-forms such as human beings. Are humans, saurs, krakens, and other planet-born species merely pawns in the gods’ millennia-long conflicts with one another?

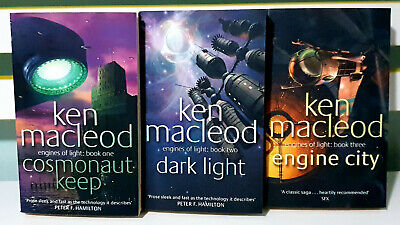

These questions and more will be explored in Dark Light (2001) and Engine City (2002). I recommend the entire trilogy.

JOSH GLENN’S *BEST ADVENTURES* LISTS: BEST 250 ADVENTURES OF THE 20TH CENTURY | 100 BEST OUGHTS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST RADIUM AGE (PROTO-)SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TEENS ADVENTURES | 100 BEST TWENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST THIRTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST GOLDEN AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FORTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST FIFTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SIXTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST NEW WAVE SCI FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST SEVENTIES ADVENTURES | 100 BEST EIGHTIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST DIAMOND AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES | 100 BEST NINETIES ADVENTURES | 75 BEST HADRON AGE SCI-FI ADVENTURES.