DOLLY YOUR ENTHUSIASM (INTRO)

By:

January 1, 2023

One in a series of 25 enthusiastic posts, contributed by 25 HILOBROW friends and regulars, on the topic of favorite Country records from the Sixties (1964–1973). Series edited by Josh Glenn. BONUS: Check out the DOLLY YOUR ENTHUSIASM playlist on Spotify.

For DOLLY YOUR ENTHUSIASM, HILOBROW’s first “enthusiasm” series of 2023, I’ve invited twenty-five HILOBROW friends and regulars to celebrate one of their favorite Country records of the Sixties (1964–1973, according to our eccentric periodization scheme).

Here’s the series lineup:

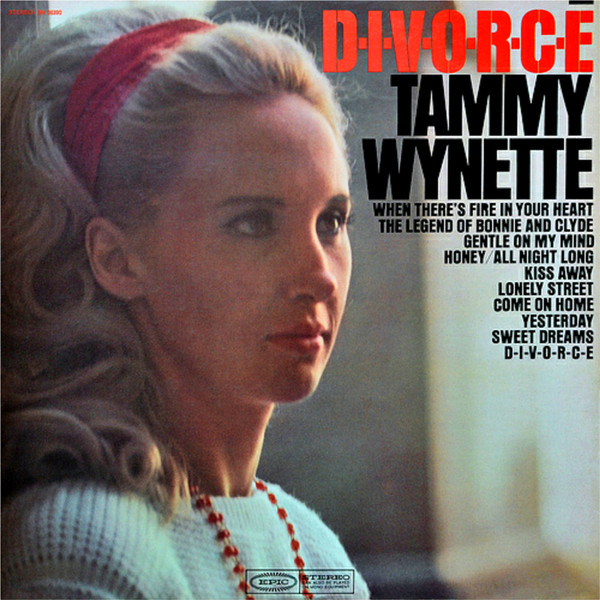

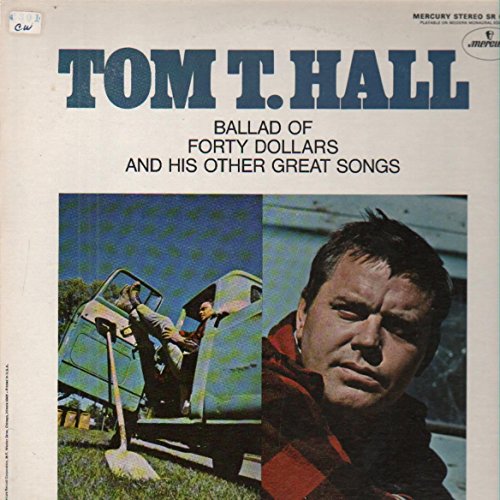

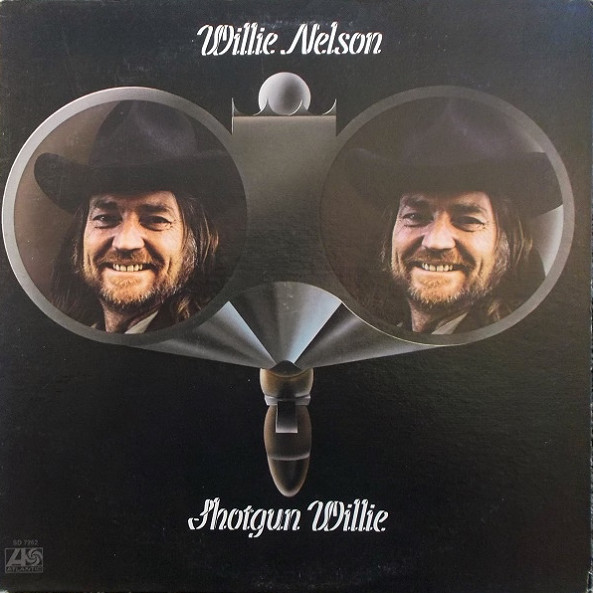

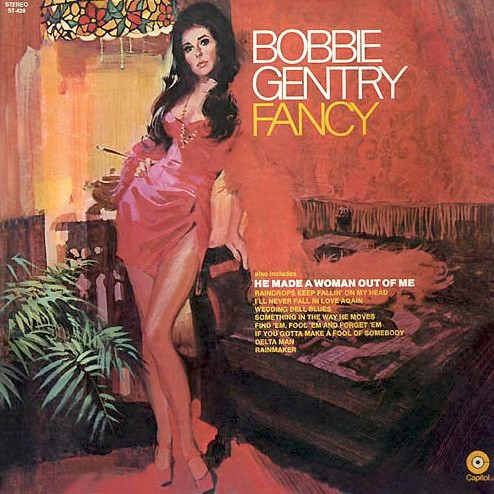

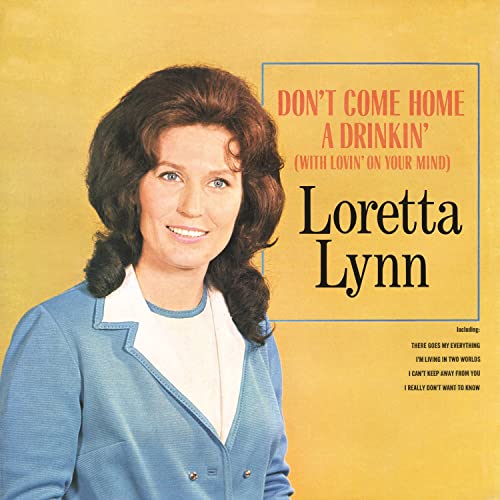

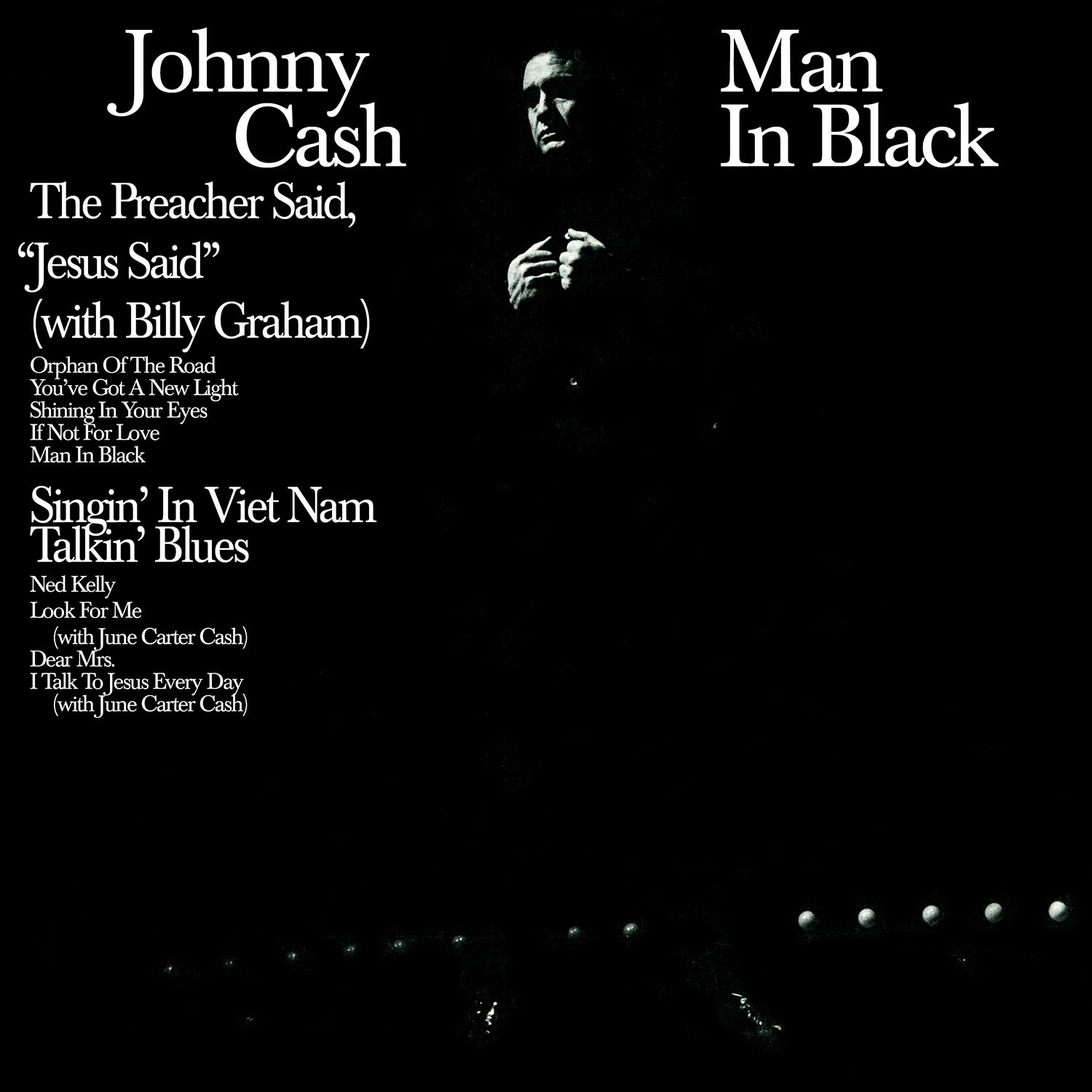

David Cantwell on Porter Wagoner and Dolly Parton’s WE FOUND IT | Lucy Sante on Johnny & June Carter Cash’s JACKSON | Mimi Lipson on George Jones’s WALK THROUGH THIS WORLD WITH ME | Steacy Easton on Olivia Newton-John’s LET ME BE THERE | TBD on TBD | Carl Wilson on Tom T. Hall’s THAT’S HOW I GOT TO MEMPHIS | Josh Glenn on Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen’s BACK TO TENNESSEE | Elizabeth Nelson on Skeeter Davis’s I DIDN’T CRY TODAY | Carlo Rotella on Buck Owens’ TOGETHER AGAIN | Lynn Peril on Roger Miller’s THE MOON IS HIGH | Erik Davis on Kris Kristofferson’s SUNDAY MORNIN’ COMIN’ DOWN | Francesca Royster on Linda Martell’s BAD CASE OF THE BLUES | Amanda Martinez on Bobbie Gentry’s FANCY | Erin Osmon on John Prine’s PARADISE | Douglas Wolk on The Byrds’ DRUG STORE TRUCK DRIVIN’ MAN | David Warner on Willie Nelson’s WHISKEY RIVER | Annie Zaleski on Tammy Wynette’s D-I-V-O-R-C-E | Natalie Weiner on Dolly Parton’s IN THE GOOD OLD DAYS (WHEN TIMES WERE BAD) | Charlie Mitchell on Stonewall Jackson’s I WASHED MY HANDS IN MUDDY WATER | Nadine Hubbs on Dolly Parton’s COAT OF MANY COLORS | Jada Watson on Loretta Lynn’s DON’T COME HOME A DRINKIN’ (WITH LOVIN’ ON YOUR MIND) | Adam McGovern on Johnny Cash’s THE MAN IN BLACK | Tom Erlewine on Dick Curless’s A TOMBSTONE EVERY MILE | Alan Scherstuhl on Waylon Jennings’s GOOD HEARTED WOMAN | Alex Brook Lynn on Bobby Bare’s THE WINNER.

I’m the editor of DOLLY YOUR ENTHUSIASM. As such, I am very grateful to the series’ contributors, many of whom have donated their honorarium to Covenant House — an agency providing shelter, food, immediate crisis care, and other services to homeless and runaway youth. I am also grateful to David Cantwell, author of Merle Haggard: The Running Kind and co-author of Heartaches by the Number: Country Music’s 500 Greatest Singles, who played a key role in rounding up most of the talent for this series — and who provided valuable insights on each series installment too.

DOLLY YOUR ENTHUSIASM kicks off tomorrow — enjoy!

PS: This is our fifth music-oriented “enthusiasm” series; the others, so far, have been dedicated to Old-School Hip Hop, New Wave, Nineties Albums, and Punk. We’ve also published dozens of “HiLo Hero” posts about Country musicians since the early days of HILOBROW; fittingly, the first of these was about Dolly Parton.

So what was Country, c. 1964–1973, about? What might we learn from these 25 records — not only about the genre but about America during those years… and today? Below, please find a few notes offering a meta-analysis of various themes that emerge (in my reading, anyway; YMMV) from among the brilliant essays contributed to the DOLLY series.

“The words to country songs are very earthy like the blues,” Ray Charles once explained. “They’re not as dressed up and the people are very honest and say, ‘Look, I miss you darlin’, so I went out and got drunk in this bar.'” (Likewise, Charlie Parker was said to have once been found listening to country songs on a jukebox; when a dumbfounded friend questioned him about it, Parker allegedly replied: “Listen to the stories, man.”) Although Country music would evolve in various ways during the Sixties (1964–1973), then, the baby that was not thrown out with the bathwater during this period was: cathartic story telling.

Our DOLLY series contributors are Country fans because they’re moved by the stories; their heartstrings are tugged. In fact, as Carl Wilson notes in his essay on Tom T. Hall’s “That’s How I Got to Memphis,” one could describe our favorite Country songs “as stories ripped not from the headlines but mysteriously as if from the listener’s own experience.”

Sometimes the story telling is folkloric: “Curless focused on local legends,” notes Tom Erlewine of “A Tombstone Every Mile” by Dick Curless, “spinning tall tales of a road known to all in Maine but which could be a fantasy to the rest of the world.” Sometimes it’s cinematic: June Carter Cash’s verbal hook “stops the clock and also delivers the scene,” Lucy Sante writes about Johnny & June Carter Cash’s “Jackson”: “She will be interrupting his slipshod attempted priapism from behind a fan, like Marlene Dietrich in The Devil Is a Woman.” And sometimes it’s operating on multiple levels: “Miller’s playful wordsmithing and cheerful melodies sometimes hid sad stories in plain sight,” notes Lynn Peril in her essay on Roger Miller’s “The Moon is High,” adding that this and other Miller records can be described as “upbeat, funny-but-sad-when-you-really-think-about-it.” “It’s a mournful, anti-capitalist screed packaged as a campfire sing-along,” notes Erin Osmon of John Prine’s “Paradise.”

In many of our favorite Country records, we’re treated to a master class in performance — in which the singer’s delivery playfully subverts or deconstructs the lyrics as written. “There is the poignant, tugging sense,” Elizabeth Nelson notes of Skeeter Davis’s “I Didn’t Cry Today,” “that the song’s outward swagger is a brave face on a process of grieving which will be a longer-than-hoped-for project.” “When she calls herself ‘Miss Smarty’ and ‘Little Country Girl,’ there is a note of shame,” writes Francesca Royster of Linda Martell’s “Bad Case of the Blues,” “but it’s cut by humor and what Katie Moulton has described as the ‘dissonance of self-knowledge.’” The music itself can also be subversive. “Hall’s music refuses to be drawn into the protagonist’s obsessive mood,” writes Wilson of “That’s How I Got to Memphis.” Carlo Rotella’s essay on Buck Owens’ “Together Again” is entirely devoted to this kind of close listening: “Tom Brumley’s pedal steel guitar comes in with the kind of tragically lush phrase you’d expect in a barroom weeper about having your heart torn in two, rather than in a song about getting back together.” And also: “The hints of dissonance in Brumley’s bends impart a sinister quality to even the sweetest slides up to a ringing major chord.”

The picaresque — episodic fiction dealing with the adventures of a roguish but appealing character, who drifts free of sociocultural and narrative conventions alike — is a crucial story telling form during this era, particularly for male protagonists. “Walk through this world with me / Go where I go,” pleads the protagonist of the George Jones song about which Mimi writes. “I did everything that I could do, but I got no ambition in life,” confesses the protagonist of the Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen song about which I write. The drifter/outlaw figure, in Country music, revalues the values not only of bourgeois culture but of his own blue-collar, get ’er done culture. He doesn’t want to work hard, or settle down; he’s an uncanny figure, both attractive and reprehensible. “Although I’ve never set foot in the South, what resonates with this westerner is the invocation of lawlessness,” writes Wyoming’s Charlie Mitchell of Stonewall Jackson’s “I Washed My Hands in Muddy Water”: “Well, there’s definitely law — but there’s a certain squirreliness in the citizenry.” Waylon Jennings’s “Good Hearted Woman” is, according to Alan Scherstuhl, “a pained consideration of the human cost of all loving and leaving that the outlaws, cowboys, and Nashville rebels Waylon championed so often got away with.” Kris Kristofferon’s “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” gives voice, suggests Erik Davis, to “a deeply American type that [Johnny] Cash called, in his televised intro to the tune, a ‘drifter of heart.’”

Drifting is going on at the level of form, too, in these performances. Writing about Linda Martell’s yodeling in “Bad Case of the Blues,” Francesca Royster suggests: “this yodel may not necessarily know where it’s going until it gets there.” Of Willie Nelson’s “Whiskey River”,” David Warner rhapsodizes: “The song ends with a languorous reverberating pedal steel in the background, drifting us into the final chorus. Memories flowing into and out of us, changing over space and time.” Our contributors can relate. Alex Brook Lynn first started to love Country when she began to drift, she recounts in her essay on Bobby Bare’s “The Winner”: “I was lost and directionless, and began to appreciate sounds from a world more used to highways and quiet dusks, houses on dirt roads, and the levity in life-long drinking habits.” “It’s not a story so much as an instruction manual for an apparatus you should never use,” Carl Wilson warns of “That’s How I Got to Memphis,” adding: “a map you should never follow.”

Drinking and drugs, of course, particularly during this era, were a crucial complement to drifting of the geospatial and existential kind alike. Of Miller’s “The Moon is High,” Lynn Peril notes:“’Moon’ doesn’t specify exactly what its protagonist is high on, but in the mid-1960s, Miller was no stranger to either alcohol or amphetamines.” And Erik Davis is explicit about the connection. “Kristofferson’s ‘Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down’ leaps, or rather drifts, into that temporal breach between sacred and profane.”

There are plenty of didactic Country records from this era, but the ones chosen by our contributors tend to be non-didactic. Quoting a Tom T. Hall interview, Carl Wilson offers this insight: “In all my writing, I’ve never made judgments. I think that’s my secret. I’m a witness.” That story telling lesson is one taken to heart by most of the artists featured in this series. Writing about Bobbie Gentry’s “Fancy,” for example, Amanda Martinez points out that “In ‘Fancy’ we get a sort of weird success story, where she enters the city, and yes, finds prostitution, but she also overcomes poverty and lives a comfortable life that she’s proud of.” Jennings’s “Good Hearted Woman,” notes Alan Scherstuhl, “doesn’t claim that it’s virtuous, necessarily, for the lover of some fool-around Charley — or, worse, an abusive Ike — to stick with him. It simply observes that that’s what a good-hearted woman does…”

Let’s give the last word on story telling to Natalie Weiner, who in her essay on Dolly Parton’s “In the Good Old Days (When Times Were Bad)” suggests that “The song is both undeniably country and deeply honest, a perfect rebuke to all the backwards-looking country songs that would tell Parton she’s better off for having to pull herself up by her proverbial bootstraps.” She adds: “May any of the contemporary artists who purport to revere her be a fraction as brave.” Amen!

I’ve already mentioned catharsis, but let’s get granular about the emotional highs and lows on offer in some of our favorite Country records of the 1964–1973 era.

Many of these records are about emotional suffering in all its manifestations: deep sorrow, grief, intense distress, loneliness and isolation, rage, shame…. Here’s Annie Zaleski on Tammy Wynette’s “D-I-V-O-R-C-E”: “Tammy Wynette knows a little something about living and loving through pain. To compensate, she often handles this ache with a subtle emotional knife twist.” And here’s Erik Davis on “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down”: “The singer wanders outside the circle of salvation, and its human manifestation as social love, his body haunted by the loneliness it will face when it comes to its dying day.” Country music instrumentation, too, evokes pain: “Brumley lands another ominous doozy,” Carlo Rotella says of Tom Brumley’s pedal steel guitar in “Together Again”: “discovering new dimensions of woe as he warps the middle tones of the IV chord.” For women in Country music, meanwhile, pain seems unavoidable. Here’s Amanda Martinez on Bobbie Gentry’s “Fancy”: “While country songs often romanticize poverty, the picture here is bleak and desperate.” And writing about Loretta Lynn’s “Don’t Come Home A Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ On Your Mind),” Jada Watson wryly notes: “Her own kind of love is not explicitly described, but it certainly does not involve a drunken husband’s pressure for late-night sex.”

Many of these songs are also about joy. For example, David Cantwell writes movingly about “the life-saving, heart-swelling joy of loving and of being loved” offered up via Porter Wagoner’s duet with Dolly Parton on “We Found It.” And importantly, Country music would have us understand that pain and joy are not so easily teased apart. Particularly once a person has cycled between the two extremes a few times. Of Skeeter Davis’s “I Didn’t Cry Today,” Elizabeth Nelson writes, “This is lost love as practical matter — painful in the extreme, but nothing a beautiful, double-tough woman of experience hasn’t handled a time or two in her trajectory.” “What does it mean to claim a bottomless joy, even in the sorrow of Black girl life and loss?” wonders Francesca Royster about “Bad Case of the Blues.” Of Linda Martell’s yodels here, Royster suggests that they “move from woe to the sheer joy of taking up sonic space, the testimony of a survivor.”

Country music inspires sentimentality and nostalgia (or memory-recalling, at any rate) — this is the conventional wisdom on the genre, despite its often being overstated. “You know [George Jones’s “Walk Through This World with Me”] right away by the plangent steel-pedal intro,” Mimi notes, before taking us on a trip down memory lane. “It is sentimental, and unapologetic about its sentimentality,” says Steacy Easton of Olivia Newton-John’s “Let Me Be There.” At the same time, many of our favorite Country records from the Sixties recognize the danger inherent in these backward-looking, muddle-headed, fantasy-prone emotional states… and urge us to interrogate our sentimentality and nostalgia even as we indulge in it.

Dolly Parton’s “In the Good Old Days (When Times Were Bad),” writes Natalie Weiner,” presciently challenged “the right-wing ideology through rose-colored (or dirt-road-hued) glasses that persists in many of the genre’s most commercially successful songs today.” Bobbie Gentry’s “Fancy,” notes Amanda Martinez, “defied the standard definition of country music as a subculture which always clings to the sentimentality of rural life.” Yet, as already noted, what’s uncanny and therefore so attractive about these records is that they insist on having it both ways — they’re never anti-nostalgic or non-sentimental. It’s difficult to put your finger on it! The music of Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen (a limit case of what we’re talking about) is “a volatile admixture of redneck sentimentality and hippie put-on,” I opine in my essay on their song “Back to Tennessee.” “‘Nostalgia’ doesn’t quite explain what songs like this make me feel,” muses Charlie Mitchell in his essay on “I Washed My Hands in Muddy Water”: “‘Homesickness’ isn’t quite right either — there’s no fireside coziness in that reckoning of home.”

Alan Scherstuhl equivocally and subtly describes Waylon Jennings’s “Good Hearted Woman” as “rambling toward self-awareness, that simultaneous myth-making and -busting that exemplifies the best Outlaw songwriting.” The same could be said of any number of the records, Outlaw- or not, admired by this series’ contributors….

The cultural era known as the Sixties (again: 1964–1973, in HILOBROW’s periodization) was one during which various sociocultural conventions which until then had appeared to be natural, inevitable, and permanent were tested and — to some extent — subverted. This was true even in Country, perhaps the genre most resistant to change of any and all sorts.

Writing about the origins of Outlaw Country, Alan Scherstuhl notes that Waylon Jennings during this era was “pushing against and RCA brass about what country could and couldn’t sound like.” Even more subversive than Outlaw, though, suggests Steacy Easton, was Olivia Newton-John’s pop-influenced “Let Me Be There,” which helped “delineate the edges of Country as a genre,” and whose “soft, ingratiating pleasure … gives us critics something new to consider, something new to defend.” Writing about Skeeter Davis’s “I Didn’t Cry Today,” Elizabeth Nelson notes: “the Beatles-esque insouciance of the opening riff with its sliding minor-major mischief.” And of Porter Wagoner’s duet with Dolly Parton “We Found It,” David Cantwell points out that “It bursts with the pop ambition Dolly was only just discovering for herself.”

The trend towards genre-curiosity and hybridization is most remarkable in those Country recordings from the era which are in some respects parodic. Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen’s “Back to Tennessee,” I claim in my essay, is “a mashup of rockabilly, honky-tonk, vintage R&B, and boogie-woogie; a proto-punk, marijuana-cured homage to the rowdy barroom country of Ernest Tubb and Ray Price.” And The Byrd’s “Drug Store Truck Drivin’ Man,” proposes Douglas Wolk, “is the best kind of brutal parody: the kind that’s also a legitimate version of the thing itself.”

Speaking of the Sixties, even the most nostalgic, sentimental, and often reactionary genre shows the influence, in many of the records discussed in this series, of the era’s wider sociocultural context.

Tom Erlewine says Dick Curless’s “A Tombstone Every Mile” is best appreciated as an artifact of the era: “It captures a specific moment when American highways and airwaves opened up for all the big and burly men who roll the trucks along.” Amanda Martinez quotes Bobbie Gentry on her support for “equal pay, day care centers, and abortion rights.” And Alex Brook Lynn, writing about Bobby Bare’s “The Winner,” asks us to consider tough-guy Tigerman’s decision to mock the glory that song’s younger man seeks as a sign of the times: “It’s hard not to imagine [songwriters] Bobby and Shel, having already served in a forgotten war, regarding the boys signing up for Vietnam in a similar fashion.”

In his essay on Johnny Cash’s “The Man in Black,” Adam McGovern suggests that America’s disenchanted youth was “the community Cash chose to first express his solemn protest and inner unease to, about imposed poverty and indefinite incarceration, about callous progress and unending war.” About the song itself, McGovern goes on to suggest, it’s “not the ‘soundtrack of a generation’ … this is a live feed from the frontlines.” “Now we can hear a zeitgeist bell in the song as well,” Erik Davis writes of “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down”: “born just as the Saturday night of the 1960s gave way to the Sunday morning of the 1970s, when a lot of things came down.”

JACK KIRBY PANELS | CAPTAIN KIRK SCENES | OLD-SCHOOL HIP HOP | TYPEFACES | NEW WAVE | SQUADS | PUNK | NEO-NOIR MOVIES | COMICS | SCI-FI MOVIES | SIDEKICKS | CARTOONS | TV DEATHS | COUNTRY | PROTO-PUNK | METAL | & more enthusiasms!