Idler Q&A (3)

By:

November 1, 2011

As previously announced, Mark Kingwell and I have collaborated on a sequel to The Idler’s Glossary, which Biblioasis published in 2008. Available for sale now, The Wage Slave’s Glossary is (like its predecessor) published by Biblioasis — and designed and illustrated by the great cartoonist Seth.

In October 2008, Mark and I were asked by the literary festival Open Book: Toronto to exchange ideas about idleness via email, and post the back-and-forth to their website. Here’s that exchange.

GLENN: At the risk of being accused of Boomer-identification, it occurred to me recently that the Beatles are a good illustration of the idler, while the Rolling Stones are a good illustration of the slacker. Wait! some might say — the Stones are still together and working, all these years later, so how could they be slackers? Ah, but that’s the thing about slackers — they don’t know when to quit, do they?

The Beatles, as represented to us in their first movie, A Hard Day’s Night, are slackers… for the moment. That is to say, they’re four young guys who are too smart and creative and fun-loving to be stuck in their job (professional musicians, en route from Liverpool to London to film a TV show — sounds really fun and cool, but a job is a job), so they play pranks on their boss/manager, they sneak away whenever they can, they refuse to help their company get ahead (by subverting every promotional opportunity). In short, they skive — that is, fail to do their duties in an instructive, glorious, larger-than-life manner. We enjoy watching them skive… but we’re comforted (politically, morally, economically) by the unspoken assumption that these artful dodgers never will quit their jobs.

McCartney, the least slackerish of the Beatles in real life, never does sneak away on his own, does he?

Sometimes, though, a slacker is an idler-in-the-making. In Help!, Magical Mystery Tour, and Yellow Submarine, the Beatles are represented to us as colorful butterflies who’ve burst free of their stifling (black-and-white) cocoons: they’re idlers. They’ve broken free of the temptation to slack forever. Now, they no longer seem to be professional musicians; they’re footloose and fancy-free, playing music spontaneously, having witty conversations, flirting, meditating, throwing themselves into play and adventure — all those things that Aristotle considered true leisure activities, because they’re desirable for their own sake. In real life, the Beatles were also evolving from slackers into idlers — and their last movie, Let It Be, shows that they did, indeed, know when to quit.

Except McCartney, of course, who immediately cranked out some solo records and then formed a new band, who toured non-stop. McCartney is neither an idler nor a slacker, I guess: He’s a workhorse, can’t help himself, poor man. As for the Stones, well, since they didn’t make fiction movies, it’s harder to make the argument.

But Jagger/Richards did write one of the great slacker anthems, “Hang Fire”:

In the sweet old country where I come from

Nobody ever works

Yeah nothing gets done

We hang fire, we hang fireYou know marrying money is a full time job

I don’t need the aggravation

I’m a lazy slob

I hang fire, I hang fire

Hang fire, put it on the wireWe’ve got nothing to eat

We got nowhere to work

Nothing to drink

We just lost our shirts

I’m on the dole

We ain’t for hire

Say what the hell

Say what the hell, hang fire

Hang fire, hang fire, put it on the wire

Doo doo dooHere’s ten thousand dollars go have some fun

Put it all on at a hundred to one

Hang fire, hang fire, put it on the wire

Yes, I know. The narrator of this song is not Mick or Keith. Supposedly it’s a working-class Englishman dispirited by the 1970s economic malaise. But who listens to it that way? We hear Mick joyfully shouting, “I’m a lazy slob!”

What about John Lennon’s “I’m Only Sleeping,” Stones fans who don’t like the sound of this theory demand to know? “I’m Only Sleeping” is a moving, inspiring idler anthem. It’s not about how lazy the narrator is (“Everybody seems to think I’m lazy”), but how screwed-up the Protestant work ethic is (“I don’t mind, I think they’re crazy/running everywhere at such a speed, till they find there’s no need”); it’s an expression of what a creative space the bed and sofa were for Lennon the idler.

Do you think this is a useful illustration, for distinguishing between idlers and slackers? As you know, doing so is the no. 2 reason I started writing an Idler’s Glossary, way back when. No. 1 reason: To back up Robert Louis Stevenson’s bold claim that “Idleness so called, which does not consist in doing nothing, but in doing a great deal not recognized in the dogmatic formularies of the ruling class, has as good a right to state its position as industry itself.”

KINGWELL: I’ve been away fishing for pike in northern Ontario, which naturally I think of as the supreme form of idling — total concentration on an activity that is, by definition, irreducible to work. They say Allah does not deduct from man’s allotted span the days spent fishing….

As you know, the idler/slacker distinction is a powerful lever. It makes clear that idling, unlike slacking, is not about work at all: it’s not avoiding work, or resenting work, or hiding from parents or spouses who think you should be working more. Idling offers an independent value which, in being independent, constructs an implicit (sometimes explicit) critique of the work-world’s norms. Because those norms are more powerful than ever, with relentless, even catastrophic, economic growth the only posited value in superheated global capitalism, idling comes ever more into its own. The idler says, don’t grow (if growth just means bigger markets). Instead, play! We are trustees of our time here, not owners of it. When it comes to selfhood and our time here, there is no property; there is only care.

The Beatles/Stones illustration is pretty apt, I think, at least in some respects. I never cared for the Beatles movies — and the Monkees’ Head was too weird for me to understand. But I do think The Monkees TV show, and semi-related hangout shows like The Banana Splits, were about idling. As far as the Stones go, I can never shake the visual scenes of recent appearances, like the Super Bowl, where they seem to be dead-eyed zombies of relentless performance, pretending to be subversive but really just extending the brand ever outward. They’re not even slackers anymore; they’re workaholics.

The only exception is Charlie Watts, who, as a jazzman, knows all about true idling. That’s why he mocks the situation with little self-deprecating nudges and embarrassed grins whenever the camera is on him.

But I was thinking of the film Withnail and I, which some related imbalances. Withnail, the deranged alcoholic out-of-work actor, is the one most desperately seeking a job, even as he masterminds the drug sprees and disastrous country trip of the narrative. He’s a slacker. The other character, I, looks more idle because more placid, ready to go along with experiences for their own sake. Yet it’s I who gets the acting job at the end, and Withnail is left to contemplate his solitude. I wonder if he somehow becomes an idler in the days after the film’s frame closes?

Which raises a question: must one idle alone, or conversely, must there be (ought there to be) a companionship of idling? Sebastian and Charles, from Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited, are the closing example of beautiful idlers in my introduction. Together, finely balanced, they achieve a kind of sublime idling, a god-like state that Aristotle hinted at. Alone, they are, respectively, merely drunk all the time (Sebastian) and bitter, sarcastic and emotionally unavailable (Charles).

Must one have a friend to idle with?

GLENN: I wish I’d been away on a fishing spree, these past few days! Alackaday, I was away on a work-related trip. Now that the Idler’s Glossary is about to be published, do you feel compelled frequently and publicly to admit (as I just did) that you work for a living? I do.

Why? Because the first question that middlebrow types interested in the Glossary will surely ask is: “So, are you an idler?” By which one’s interlocutor, whom one might call Terry Gross, strictly for visualization purposes, will mean, “Do you work for a living, idling expert? Or are you a hypocrite?” One will want to protest that Terry doesn’t fully understand what an idler is… but in so protesting, one might give the misleading impression that idling is merely a groovy state of mind. So one will also want to make Terry understand that sometimes an idler must work, just as a worker once in a while can find a way to idle. One will strive to convey, furthermore, one’s conviction that it’s critical to distinguish (with Hannah Arendt) between working and laboring, not to mention one’s notion that work and play aren’t polar opposites. One ought also to make the point that the idler, as described indirectly in the Glossary, is an ideal type. As Kierkegaard has Johannes de Silentio remark of the Knight of Faith (I’m quoting loosely), “I’ve never met one, nor would I necessarily know such a man if I saw him.”

Instead of trying and failing to cram all of the above and more into a complex response to what might sound, to Terry and others, like a simple question, wouldn’t it be easier to blurt out, before Terry even opens her mouth: “By the way, I work for a living.”

Regarding the Beatles’ movies, you’re right, the plots are not interesting, the acting is not good, the teeth are crooked. It’s the mise-en-scène I dig: the layout of the protagonists’ living spaces, and the emotional tone generally. Which brings me to your question about idling as a group activity. Personal experience, and a close study of the historical record, indicates that idlers often thrive in small, agonistic groupings. Intellectual, artistic, or political collectives, that is to say, which don’t collectivize. Each member of such a group is supported in, and valued for his or her singularity. The tradeoff is a temporal one: Such groups rarely last long. Whereas artistic collectives composed of mere individuals (as opposed to singularities), from the Beat Generation to the Spice Girls, to name two, can survive indefinitely. Perhaps the distinction I’m struggling to express here is the Vonnegutian one between the karass (whose members are all working toward the same purpose, like the fingers in a cat’s cradle, whether they know it or not) and the false karass? Hmm, not sure. To complicate matters, some idler groupings are infiltrated by slackers — you mention Withnail and I. When the members of such groups are young, it can be quite difficult to detect which of them will “grow up,” which of them are crazy, and which of them are dyed-in-the-wool idlers. But I suppose that’s precisely the secret of such groups’ agonistic pleasures.

A fun and provocative literary example of the agonistic idler grouping is the academic department as portrayed in mid-century campus novels. I’ve had no first-hand experience with English or Philosophy departments, except as a student. What’s your take? Any idlers to be found in them? Is academe the perfect job for an idler? (Summers off!) Or does the PhD process spit out all the would-be idlers, these days?

KINGWELL: The range and number of references in that post are impressive! If I were feeling agonistic, I would compete back with my own array of favorites. I’m too lazy to look anything up right now, though, so I won’t.

But I like the way you subtly indicate that competition, struggle, even effort (of some kinds) is entirely consistent with idling. Lots of play is structured competitively, for example, and surely part of the reason people still watch professional sports, despite all their pathologies, is that they crave the spectacle of play. Thus, too, the outrage that attends perceived violations of the norms of play — cheating, drugs, underage Chinese gymnasts or overage Taiwanese little leaguers. Something has been violated in pursuit of competition — winning as the only thing — and people miss that something. Competition itself is not the enemy.

Two further related thoughts: (1) Still thinking of fishing, the way anglers compete strikes me as potentially the ideal form. Cheerful, sarcastic, only ever semi-serious, and directed at nothing important. First, biggest, and most. This sort of thing may be rather male — it certainly crystallizes my relationships with my two brothers — but it’s also got some kind of universal appeal. We’re bonding by competing, only over nothing. Excellent!

(2) We’re familiar with Debord’s analysis of ‘the society of the spectacle’, drawn in part from Huizinga’s Homo Ludens, whereby, among other things, forms of play are rendered into large-scale non-participatory crowd events that succumb to the work-week logic. The baseball game is enjoyed not in itself, but as reward for past work (‘working for the weekend’) and rest for future work (‘R&R’). What a sad thing to do to play.

You can still watch a professional baseball game in playful spirit, I think, just as you can be paid to do what you like to do. So on the Terry Gross question, after being briefly tempted to quote bits of the infamous Gene Simmons interview, I would just say to her, Sure I’m an idler — in my best moments. These aren’t as frequent as I’d like, and sometimes my job is just boring work (grading papers, attending committee meetings); but mostly it’s joy. So the fact that, say, I have three books with my name on the cover appearing in 2008 — one of them ours — is an indication of just how productive my idling can be, not that I’m a hypocrite.

Like you, I’m a fan of those campus novels. Where did that genre go? But I mostly found them terrifying, especially Lodge’s Small World and the twinned dark moons of McCarthy’s Groves of Academe and Jarrell’s Notes from an Institution. Even in comedy, they made academic life seem just as desperate, political and hopeless as I imagined, toiling away at my PhD during the late 1980s. Amis’s Lucky Jim, both the funniest and the most savage satire of academic life, ends with the protagonist giving up his misplaced academic ambitions. It was like a sign that said, “Fire! Get out!”

My own experience indicates that academic life is not at all about idling the way most people do it. PhD years do indeed weed out the interesting wayward ones, leaving only the directed and disciplined, the bloody-minded and the close-minded. If you can hack that, though, and secure the degree, along around seven years into the job — I spent the first seven years of my post-doctoral life in temporary jobs and rickety contracts — there is just the slightest chance that you can just let go and enjoy the fact that this is the best fun there is. That’s if you haven’t surrendered your soul along the way.

Then, strangely, they give you tenure and other things that make it silly to leave. I agree my experience is not typical. Most of my younger colleagues are hyper-competitive, uber-professionalized wonks with no life or interest outside of their narrow specialty. They also complain a lot, about pretty much everything. Not a recipe for idling, even with the summers free of teaching….

GLENN: Thanks for the account of life in academe. The Glossary is packed with descriptions of the idle life, or idle moments… but it doesn’t have much to say about the effort required of the would-be idler to arrive at idleness, does it? That’s something it has in common with other utopian writing, I suppose: To author and reader alike, the utopian city is more fascinating than the journey required to arrive there. It has too frequently been suggested that idleness is a style of life instantly available to whoever attains the proper worldview; i.e., that it’s achieved not via work, competition, struggle, but rather by

quitting, surrendering, chilling. However, what you say about the PhD process, and the life of the associate or adjunct professor, bolsters my gut feeling that if idleness is indeed like a utopian city, then that city is Oz: Dorothy can’t enter into it without first working and quitting, competing and surrendering, struggling and chilling. It’s complicated!

Besides L. Frank Baum, what writers provide us with a visceral sense of the journey toward idleness?

In Hawthorne’s Blithedale Romance, the narrator — who has left his desk job in Boston, and joined a commune in nearby West Roxbury, the neighborhood where I now live — likens the start of his fellow communalists’ journey to a prison-break. “We had left the rusty iron frame-work of society behind us,” he says. “We had broken through many hindrances that are powerful enough to keep most people on the weary tread-mill of the established system, even while they feel its irksomeness almost as intolerable as we did.” He has little to say about the journey itself, though. Same with, for example, Hilton’s Lost Horizon.

Henry Miller? Maybe, yeah: Although his first novel kicked off with the narrator’s paean to his newfound freedom, much of what’s compelling about Miller’s fiction is the semi-autobiographical treatment of the years before the author abandoned his wife, child, job, and country and headed, at 40, to Paris.

Who else?

Also, two cheers for competition, yeah! Speaking of aspects of idling about which nothing is mentioned in the Glossary, in “Idling Toward Heaven,” your brilliant introductory essay, you generously and perhaps not entirely seriously claim that “everything you need to know about how to conduct a life lies within these covers, if only sometimes by implication and omission.” Now, slipping a small-el lebensphilosophie into the Glossary was indeed my fondest wish, but I couldn’t pull it off… because of questions like: Is the idler competitive or uncompetitive? Cheery or cranky? Fit or fat? Proactive or reactive? Silly or solemn? Chaotic or lawful? Focused or distracted? Dirty or clean? Conservative or liberal? Coke or Pepsi? One could go on like that all day.

Help me out, Mark. Can a philosophy of life get away with dodging such questions?

KINGWELL: I think you nail the essential difficulty: transition. I came up with the Idler’s Eleven-Step Program for Recovery (Because We’re Too Lazy for Twelve) because it seemed there was a therapeutic, life-changing message implicit in the Glossary. And of course because work can seem like an addiction, the most widely suffered and state-sanctioned form of addiction there is.

Here are the Eleven Steps, which are closely modelled on AA’s more serious twelve:

1. We admitted we were powerless to make work less boring or harmful — that our lives as salarymen had become unmanageable.

2. Came to believe that idleness was greater than our efforts and could restore us to sanity.

3. Had an idle thought to turn our lack of will, and so our lives, over to the care of idleness as we understood it.

4. Made a searching but relaxed inventory of our working selves, a. k. a. our Inner Drudge.

5. Admitted to the way of idleness, to ourselves, and to any other human being within easy earshot the exact nature of our wrong ideas about the need to work.

6. Were entirely ready to have idleness remove all these defects of character, as long as it didn’t involve any effort on our part.

7. Humbly asked the way of idleness to remove our shortcomings since we couldn’t really be bothered.

8. Considered a list of all persons we had worked for, and became willing to tell them all to get stuffed.

9. Contemplated direct address to such people wherever possible, except when to do so would inconvenience us.

10. Continued to take casual personal inventory, and when we were slack rather than idle promptly admitted it.

11. Sought through laziness and indolence to improve our conscious contact with the way of idleness as we understood it, praying only for knowledge of its non-will for us and the power not to carry that out.

Obviously this recovery-program tone is only half-serious, as the paradoxical final step indicates. It is, however, *half*-serious. The final message of The Idler’s Glossary really is, as Rilke said of art, that you must change your life.

How? Well, as I wrote in the introduction, the glossary is the most idle of textual forms. What could it mean for life lessons to be contained ‘by implication or omission’ — present by their absence, pushing off against the cultural surround? Yes, something like that. The Glossary succeeds, in other words, precisely by failing: it instructs by forbearing from instruction, it teaches without lessons, it enacts change without appearing to do anything.

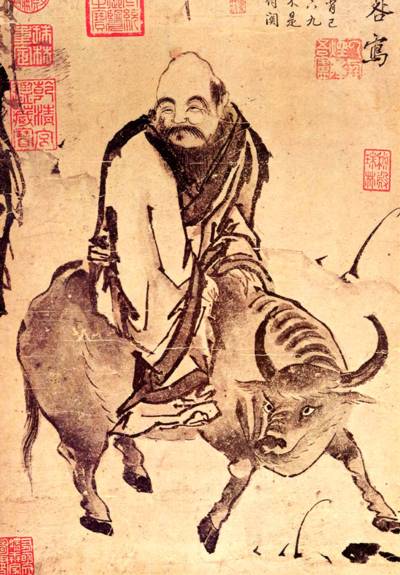

That’s one reason my personal favorite idler is Lao Tzu, as I suggest in the intro. The tao is not just a letting-go, a chill; it takes effort and dedication and concentration. But not striving in the usual sense, not effort as typically understood. Like the Tao Te Ching, one reaches the end of the Glossary feeling that something profound has been communicated, that life must be seen differently, but it is almost impossible to articulate that feeling into the dicta of a lebensphilosophie. (I know, because I teach Lao Tzu every year to 500 first-year undergraduate philosophy students, and it — together with my lectures about it — leave most of them baffled. Most, but not all!)

You asked about writers who plot the transition. My best example is Bataille, in The Accursed Share. In the preface he notes the deep irony of writing a book about the futility of human energy transfers — what he calls ‘special economy’ — when all writing is just another such transfer. This to say nothing of actually publishing a book, and hoping (is it hope?) that other humans (how many? at what price?) will purchase and (perhaps) read it.

At times, Bataille says, he abandoned the work because his own insight suggested work was a fatally compromised system. But he perseveres, and now presents the book to us under the sign of his own insanity. (“Only a madman would make these claims. I am that madman.”) Bataille seems to suggest that the insights are more powerful than the force of logic; contradiction dissolves into insightful paradox. And lucky for us, because it’s a brilliant book. When you reach the end, with the almost mystical claims about true sovereign self-consciousness being consciousness of nothing, the book seems to self-immolate. But there it is, still in yours hands. You’re a different person! Some of the best philosophy books have this self-obliterating quality: I think of Wittgenstein’s Tractatus, which ends with the idea that the book is a ladder. Once you have climbed the steps, you can throw the ladder away.

I’d like to think that, in its modest way, our book is such a ladder. Though, to be precise, it has no steps, only multiple views. So maybe a kind of view-master or kaleidoscope? And let us ask readers not to throw it away when finished. Instead, make it a gift to someone else.

ALSO SEE: Rushkoff vs. the 1% (1) | Tactical Utopia | Feral Dissent | Don’t Mourn, Organize | Occupying Our Gardens | Grand Theft Politics | The Black Iron Prison | News about the Wage Slave’s Glossary