Fitting Shoes (7)

By:

September 13, 2010

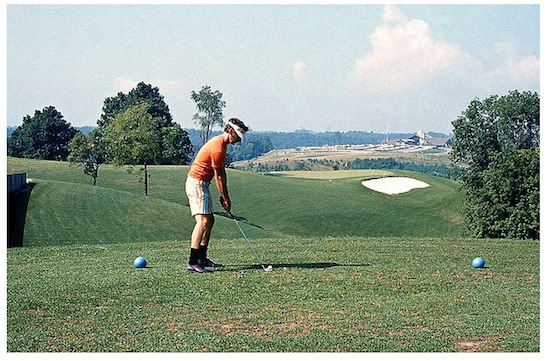

“[Gary Lambert] was printing images from his parents’ ill-fated decade of Connubial Golf…. In the other photo Alfred [Lambert] was wearing tight shorts and a billed Midland Pacific cap, black socks and prehistoric golf shoes, and was addressing a white grapefruit-sized tee marker with his prehistoric wooden driver and grinning at the camera as if to say, A ball this big I could hit!” — Jonathan Franzen, The Corrections (2001).

Tough one!

I don’t mean that it’s difficult to find info on vintage golf shoes — after all, there’s an entire category devoted to ’em on eBay. However, figuring out what make/model of shoes that Gary Lambert (the character contemplating a photo of his father, Alfred) might consider “prehistoric” is tricky because Jonathan Franzen is obsessed with shoes. And with golf, too.

In Franzen’s debut novel, The Twenty-Seventh City (1988), Martin Probst dons a pair of new jeans (“prewashed black denim jeans”), then agonizes over which shoes to wear with them. “Everything was leisure or oxford or rubber-toed or tasseled…. [he] burrowed through sixty pairs of footwear, shoes, fins, skates, rubbers, thongs, mukluks….” etc., on and on to the point of absurdity: “white espadrilles from Spain, embroidered Oriental mules, painted shoes from Holland,” etc., etc. There’s also a rant about flip-flops in Franzen’s latest novel, Freedom: “It’s like the world is their bedroom,” he has the character Patty complain. “And they can’t even hear their own flap-flap-flapping, because they’ve all … got their earbuds in.”

Probst’s father, we learn, worked at a Gamm’s shoe store and was “very particular about his clothes.” Franzen — like Tom Wolfe, a writer of manifestos about sweeping socio-cultural novels, is particular, even exacting, about his characters’ clothes and shoes. So how to pinpoint the make and model of Alfred Lambert’s golf shoes? Andrew O’Hehir once wrote about Franzen’s “ability to locate hidden meaning in ordinary places and ordinary moments,” so let’s first attempt to figure out what golf means to Franzen.

For Franzen, golf symbolizes a social order in which sociopaths (who spout platitudes about family values) succeed effortlessly while men and women of sensibility and conscience stumble along haplessly in their wake. Golfers are jerks: in Freedom, Patty, a high-school athlete, is date-raped by Ethan, a sociopathic boarding-school student “who didn’t do any sports except golf.” In “Control Units,” a piece of reportage critical of America’s prisons, Franzen recounts a visit to a Florida golf course “built in part to appeal to prison bureaucrats, who were reputed to be keen linksmen.” And in an essay on Charles Schulz’s Peanuts*, Franzen notes that his father’s enjoyment of golf and bridge consisted in “perpetually reconfirming that he was useless at the one and unlucky at the other”; he’s signaling that his father is a lovable loser, a Charlie Brown figure — i.e., a man of sensibility and conscience out of step in a competitive, unforgiving midwestern social milieu.

I’ve been over-simplifying. Franzen doesn’t merely discover significance in golf; he also invests the game with significance. Golf is one of a variety of lenses through which Franzen examines the way in which our everyday actions either make us complicit with or signal rejection of (correction for, rather, since rejection is impossible) our families’ fucked-up values. Reading the New Yorker essay (“Letter from the Yangtze Delta”) in which Franzen describes how he traveled to China in order to connect the dots between an industrial system that destroys birds’ habitats and one that churns out fake birds — specifically, a plush puffin golf club head cover, made in China, that one of his older brothers gave him, we can only marvel: Wow, that’s symbolically rejecting/correcting for your brother’s unconsidered materialism the hard way.

Rejecting our families’ values is impossible, for Franzen. In his world, men and women of conscience and sensibility are forever looking for ways to connect with their sociopathic family members. Not just in his fiction: in the essay “House for Sale,” for example, he beats up on himself for playing golf with his brother-in-law while Hurricane Katrina was destroying New Orleans. In the same essay, however, he’s careful to let readers know that he wasn’t golfing well: he kept hooking balls into the woods and topping into water hazards. Franzen, too, is a Charlie Brown figure.

All of which requires us to reconsider the Oprah Winfrey Book Club flap. Commentators claimed that Franzen was a highbrow who’d erred by making a snarky, anti-middlebrow comment about Oprah and her viewers, but that isn’t so! What Franzen actually said on NPR’s “Fresh Air” was this: “So much of reading is sustained in this country, I think, by the fact that women read while men are off golfing [emphasis added] or watching football on TV or playing with their flight simulator or whatever. I worry — I’m sorry that it’s, uh — I had some hope of actually reaching a male audience and I’ve heard more than one [male] reader in signing lines now at bookstores say ‘If I hadn’t heard you, I would have been put off by the fact that it is an Oprah pick.”

Franzen wanted to connect with male golfers — sociopaths who cover their clubs with plush puffin head covers made in China. Why? Because that’s what it means to be part of a family.

In The Corrections, Gary is a status-obsessed investment banker (“What Gary hated most about the Midwest was how unpampered and unprivileged he felt in it”), and therefore — in Franzen’s moral calculus, he is doubtlessly an excellent golfer (though we never find out one way or the other). Alfred, on the other hand, is a Charlie Brown type who grins at the camera as if to say, A ball this big I could hit! What make and model of golf shoe might Alfred Lambert — not to be confused with golfer Albert Lambert — have worn during the decade of connubial golf? Presumably, that decade was the Seventies, so Alfred’s “prehistoric” shoes would date back even farther, I think to the Sixties.

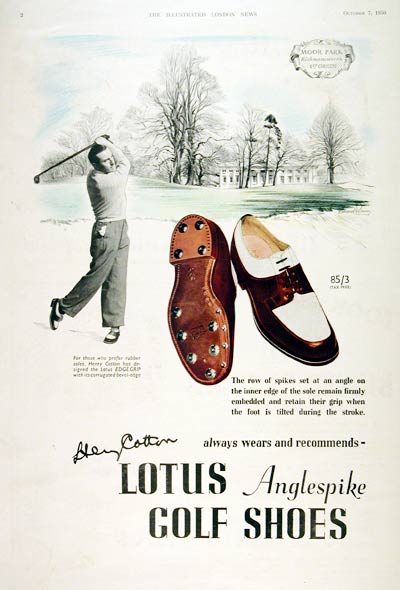

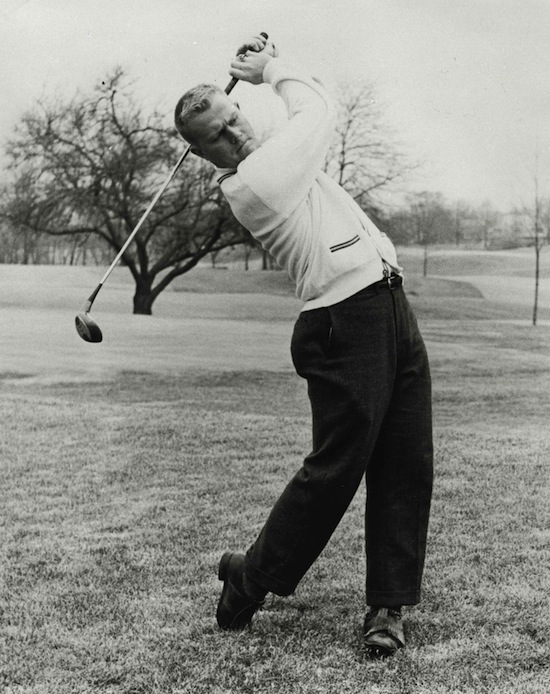

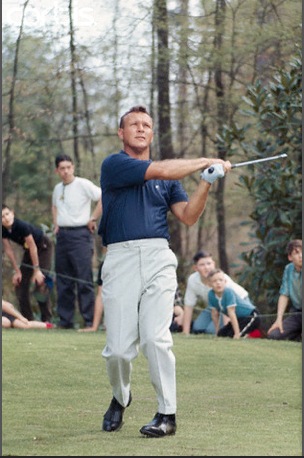

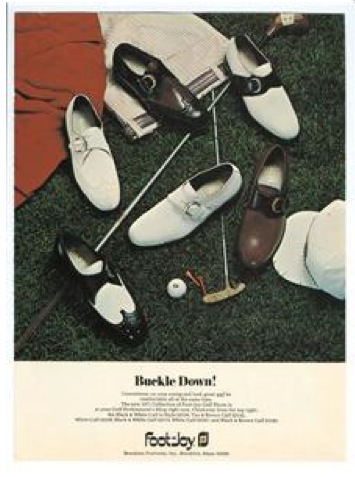

My own brother-in-law (not a sociopath, but I don’t want to malign his golf game) tells me that in the mid-Sixties Arnold Palmer, Jack Nicklaus, Sam Snead, and most other golfers wore solid-colored (black or brown) golf shoes with fringed flaps over the laces. A little research proves him right:

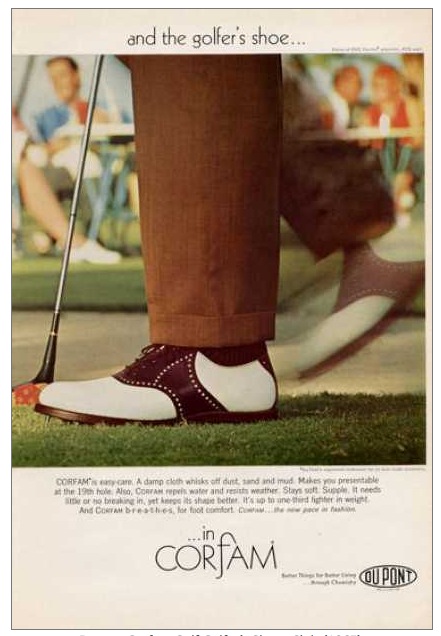

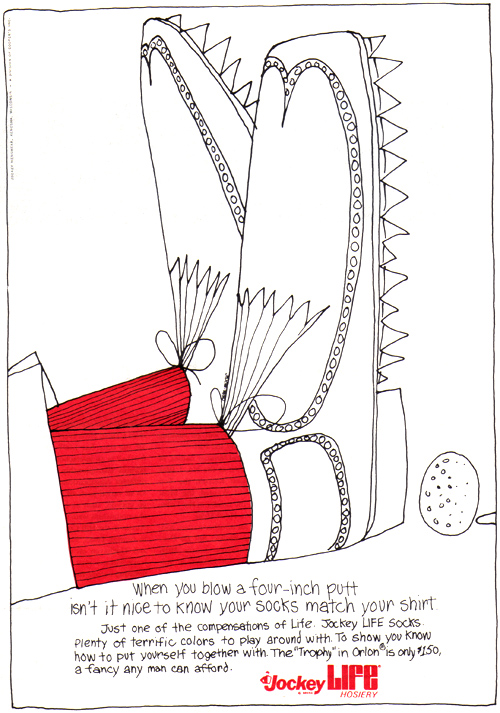

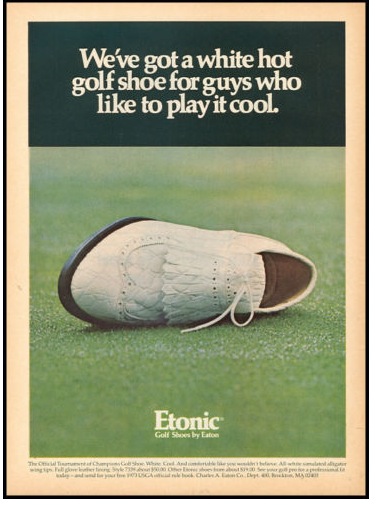

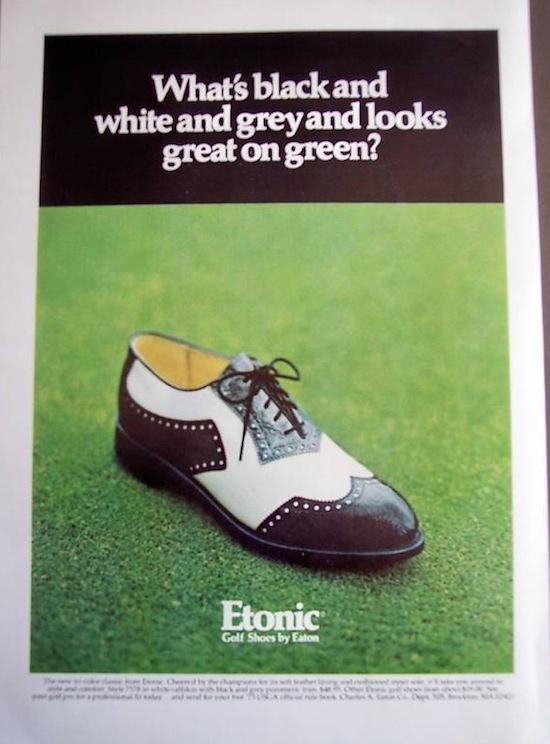

By the mid-Seventies, my brother-in-law recalls, a two-tone (Fifties-style) saddle shoe — sans flap — had become trendy. We can see the change happening in these advertisements:

Alfred is a Charlie Brown type — a man of conscience and sensibility. His humane, un-sociopathic values turn him into one of life’s losers — so he’s out of it. This is Alfred’s strength! But from Gary’s perspective, it’s a weakness — he sees his father as a hapless victim, and as a burden. Alfred was likely wearing brown FootJoy wingtips, c. 1965 — with flaps, of course.

* Is Patty, the tomboy athlete in Franzen’s new novel, named for Peppermint Patty?

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).

An occasional series seeking to determine the make and model of fictional footwear.