BROKEN KNOWLEDGE (9)

By:

November 9, 2025

University of Toronto philosopher Mark Kingwell and HILOBROW‘s Josh Glenn are coauthors of The Idler’s Glossary (2008), The Wage Slave’s Glossary (2011), and The Adventurer’s Glossary (2021). In 2022, they engaged in an epistolary exchange about science fiction. Via the series BROKEN KNOWLEDGE, the title of which references Francis Bacon’s philosophy, HILOBROW is pleased to share a lightly edited version of their exchange with our readers. Also see Josh and Mark’s previous exchange 49th PARALLEL.

BROKEN KNOWLEDGE: FIRST CONTACT | WHAT IF? | A HYBRID GENRE | COUNTERFACTUALS | A HOT DILUTE SOUP | I’M A CYBORG | APOPHENIC-CURIOUS | AN AESTHETICS OF DIRT | PAGING DR. KRISTEVA | POLICING THE GENRE | FAMILIAR STRANGENESS | GAME OVER | THE WORLD VIEWED | DEFAMILIARIZATION | SINGULAR CREATURES | ALIEN ARCHAEOLOGIST | THE PHENOMENOLOGY OF SCREEN-TIME | HOMO SUPERIOR | EVERYTHING IS US.

12th October, 2022

BOSTON

Since your letter of the 1st, you got out of the hospital — but then returned. Here’s hoping that by the time I receive your next letter, you’ll be at home and healthy! Speaking of your letter, which is a preview of your next project, on cinema and the uncanny, I couldn’t be more excited to follow along as you think and write about this topic — and I’ll be the first in line to read it.

Let me start by responding very briefly to your question about genre. While I agree with Lucy Sante, who’s said to me in conversation more than once that “it’s all genre” (that is, “realistic” literature should not be given a pass as somehow transcending genre), I also really enjoy genre-negotiation. I’m glad that people will forever continue to sort works of fiction into genres — and I’m also glad that writers are forever breaking those rules. Leigh Brackett’s The Sword of Rhiannon, Poul Anderson’s Three Hearts and Three Lions, even Heinlein’s deeply flawed Glory Road — are fun Golden Age-ish examples of “science fantasy,” for example. During the Radium Age, though, almost everything is science fantasy. I think that talking about “science fantasy” isn’t really possible until sf’s borders were firmed up, which I want to talk about more now. So thanks for bringing up abjection….

I mentioned in my note of 20th September that the very concept that the science fiction genre is thought to have had a Golden Age (c. 1935–1965) was the result of a successful propaganda effort on the part of sf editors (particularly John W. Campbell of Astounding/Analog) and writers (Isaac Asimov, for example) from that time period. This effort of theirs, I’m not the first to point out, cannot be separated from the “policing” in which these same men engaged — i.e., shoring up sf’s “borders,” declaring certain tropes or themes either acceptable or unacceptable. When Campbell took over Astounding in 1937, he transformed that sf pulp magazine from (what he regarded as) an impure, generically compromised clearinghouse into (what he regarded as) a scientifically sound enclave. This was a highly gendered undertaking. In the name of genre purity, anything “feminine” (in the worldview of Campbell, et al.) had be excised from sf — romance, for example, but arguably also domestic life, child rearing, leaky bodies, the irrational, the spiritual, etc. Paging Dr. Kristeva! Nothing less than the symbolic order was at stake, one senses, for Campbell and his anti-abjection crew, as they set about establishing firm rules and laws for sf.

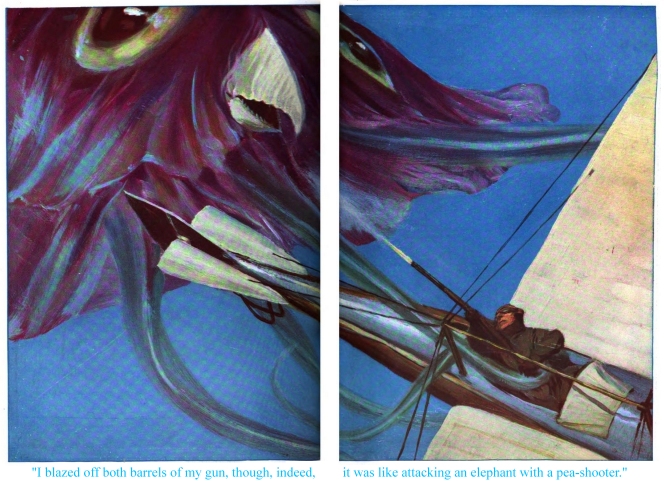

The abject, Kristeva tells is, has to do with “what disturbs identity, system, order. What does not respect borders, positions, rules.” This was precisely the source of proto-sf’s uncanny power during the genre’s formative Radium Age years — its fluidity, its tentacle/amoeba-like slipperiness and malleability. (There are so many tentacles to be found in Radium Age proto-sf, as I note in my introduction to the Voices from the Radium Age collection.) Proto-sf was messy and sloppy, it defied genre rules — fun! And then along came the self-appointed grownups — at which point we get Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon, shiny new spaceships, “hard” sf writing. This is not exactly correct, of course — space opera predates Campbell. Verne and Wells were “hard” sf writers of a sort, as were others during the Radium Age. But these were tendencies; Campbell, et al., made them law. The return of “dirt” of various sorts to sf, during sf’s New Wave era of c. 1964–1983, notably in 1979’s Alien, was a repudiation of the Golden Age.

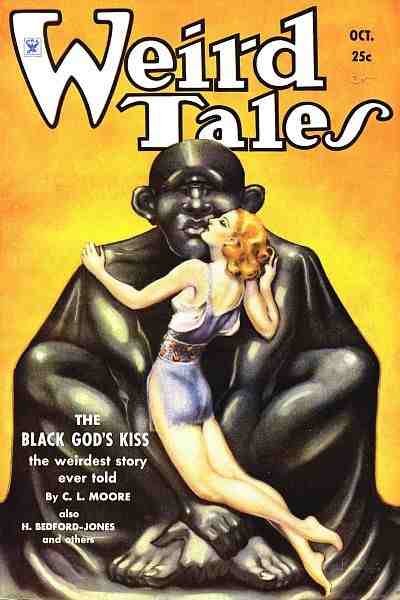

Susanne F. Bozwell’s essay “‘Whatever it is that compels her to write so seldom’: Network Analysis and the Decline of Women Writers in Pulp Science Fiction” (in a recent issue of Extrapolation) does an amazing job of demonstrating how — during the 1926–1946 pulp magazine period — women sf writers were published in ways that made it nearly impossible to gain economic stability and prestige in the pulps. They weren’t simply banned — that would have been too obvious. But unlike male sf writers, who were published again and again by the same sf magazines, thus giving them status within the community (and a regular paycheck), most women sf writers — perceived, around this time, as the vector of the abject into the genre — were effectively homeless. Astounding published many male writers again and again, but C.L. Moore was the only female writer with repeat bylines there. Wonder had Leslie Stone — and that’s it. Amazing — Gernsback was the least sexist of the pulp sf editors — had Clare Winger Harris, L. Taylor Hansen, and (also) Leslie Stone. The only pulp with more than ten regular female contributors was Weird Tales — which, like proto-sf before the pulp era, was genre-fluid and, yes, weird.

Let me just add a smoking gun or two from Bozwell’s essay. In 1938, she finds male readers writing letters to sf pulps approvingly describing these magazines as “free-from-women’s stories,” and no place for “the age-old love idea.” A young Asimov suggests, in one such letter, that pulp magazines that feature impure sf (i.e., featuring romance) alienate male readers who are “far superior in intelligence, in emotional maturity and in sensibility.” No wonder that many female sf authors wrote pseudonymously.

Regarding Amis — yes, his sf-ish efforts are my least favorite of his books. I approve of his efforts to help sf be taken seriously by highbrow literary critics, with New Maps of Hell, though of course the general public had already been won over — at least since the success of The Martian Chronicles in 1950. Amis is one of the anti-abject squad, I’m sorry to report. He makes the argument, in New Maps, that mature sf first established itself in the mid-1930s, “separating with a slowly increasing decisiveness from [immature] fantasy and space-opera.” He’s parroting the Campbell agenda. The Cold War rhetoric of maturity should always make us suspicious! I think of Reinhold Niebuhr, in 1952, describing 1930s social/political utopianism as “an adolescent embarrassment.” Or Dwight Macdonald (an unrepentant utopian) furiously rebuking Daniel Bell for chuckled indulgently, in a 1958 review of Macdonald’s political essays: “I don’t see why a drastic rejection of what is necessarily means pure-heart-but-wooly-wit; in fact, I think I am the one that has tried to think and to analyze quite objectively, and that you… may simply be unwilling to go beyond a certain point in ‘facing up to things,’ that point being the farthest reach of conventionality.”

Can we keep talking, here, about the uncanny and the abject — a little longer, anyway? We can get back to genre later. In “Notes on Camp,” Sontag warns that “a sensibility (as distinct from an idea) is one of the hardest things to talk about.” The same is true when it comes to talking about the uncanny — an eerie experience of “neither/nor” phenomena, made most evocatively manifest in horror and sf movies. Any theorist tackling the uncanny is engaged in a high-wire act — remaining attentive to the emotional, psychological, and physical effects of viewing such unusual entertainments, while simultaneously analyzing not only what the experience is like but how the movie manages to affect the viewer the way it does, e.g., via the various modalities specific to that medium. There are few thinkers or writers better equipped to walk such a tightrope than you! Can you talk a little bit about your methodology — I mean, for example, do you closely observe how your body and mind respond to the sf/horror (another genre mashup) movies you mention: Alien, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, The Thing, the Battlestar Galactica reboot, District 9? How so?

Josh

ALSO SEE: Josh’s BEST 250 ADVENTURES of the 20th CENTURY list | Mark on BATTLESTAR GALACTICA and THE HONG KONG CAVALIERS | Mark and Josh’s exchange 49th PARALLEL.