REPUBLIC OF THE SOUTHERN CROSS (8)

By:

May 14, 2022

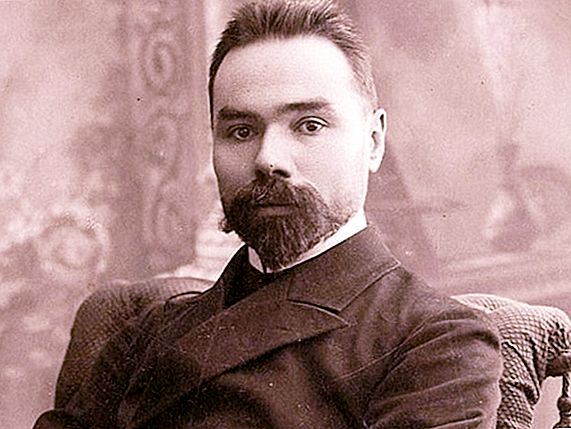

Valery Bryusov

HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize Valery Bryusov’s 1907 proto-sf story “The Republic of the Southern Cross” (“Respublika Iuzhnogo Kresta”) for HILOBROW’s readers.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9.

It must be added that on the 21st of July the crowd took the Town Hall by storm and its defenders were all killed or scattered. The body of Deville has not yet been found, and there is no reliable evidence as to what took place in the town after the 21st. It must be conjectured, from the state in which the town was found, that anarchy reached its last limits. The gloomy streets, lit up by the glare of bonfires of furniture and books, can be imagined. They obtained fire by striking iron on flint. Crowds of drunkards and madmen danced wildly about the bonfires. Men and women drank together and passed the common cup from lip to lip. The worst scenes of sensuality were witnessed. Some sort of dark atavistic sense enlivened the souls of these townsmen, and half-naked, unwashed, unkempt, they danced the dances of their remote ancestors, the contemporaries of the cave-bears, and they sang the same wild songs as did the hordes when they fell with stone axes upon the mammoth. With songs, with incoherent exclamations, with idiotic laughter, mingled the cries of those who had lost the power to express in words their own delirious dreams, mingled also the moans of those in the convulsions of death. Sometimes dancing gave way to fighting — for a barrel of wine, for a woman, or simply without reason, in a fit of madness brought about by contradictory emotion. There was nowhere to flee; the same dreadful scenes were everywhere, the same orgies everywhere, the same fights, the same brutal gaiety or brutal rage — or else, absolute darkness, which seemed more dreadful, even more intolerable to the staggered imagination.

Zvezdny became an immense black box, in which were some thousands of man-resembling beings, abandoned in the foul air from hundreds of thousands of dead bodies, where amongst the living was not one who understood his own position. This was the city of the senseless, the gigantic madhouse, the greatest and most disgusting Bedlam which the world has ever seen. And the madmen destroyed one another, stabbed or strangled one another, died of madness, died of terror, died of hunger, and of all the diseases which reigned in the infected air.

It goes without saying that the Government of the Republic did not remain indifferent to the great calamity which had overtaken the capital. But it very soon became clear that no help whatever could be given. No doctors, nurses, officers, or workmen of any kind would agree to go to Zvezdny. After the breakdown of the railroad service and of the airships it was, of course, impossible to get there, the climatic conditions being too great an obstacle. Moreover, the attention of the Government was soon absorbed by cases of the disease appearing in other towns of the Republic. In some of these it threatened to take on the same epidemic character, and a social panic set in that was akin to what happened in Zvezdny itself. A wholesale exodus from the more populated parts of the Republic commenced. The work in all the mines came to a standstill, and the entire industrial life of the country faded away, But thanks, however, to strong measures taken in time, the progress of the disease was arrested in these towns, and nowhere did it reach the proportions witnessed in the capital.

The anxiety with which the whole world followed the misfortunes of the young Republic is well known. At first no one dreamed that the trouble could grow to what it did, and the dominant feeling was that of curiosity. The chief newspapers of the world (and in that number our own Northern European Evening News) sent their own special correspondents to Zvezdny — to write up the epidemic. Many of these brave knights of the pen became victims of their own professional obligations. When the news became more alarming, various foreign governments and private societies offered their services to the Republic. Some sent troops, others doctors, others money; but the catastrophe developed with such rapidity that this goodwill could not obtain fulfilment. After the breakdown of the railway service the only information received from Zvezdny was that of the telegrams sent by the Nachalnik. These telegrams were forwarded to the ends of the earth and printed in millions of copies. After the wreck of the electrical apparatus the telegraph service lasted still a few days longer, thanks to the accumulators of the power-house. There is no accurate information as to why the telegraph service ceased altogether; perhaps the apparatus was destroyed. The last telegram of Horace Deville was that of the 27th of June. From that date, for almost six weeks, humanity remained without news of the capital of the Republic.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.