FRIEND ISLAND (1)

By:

May 9, 2021

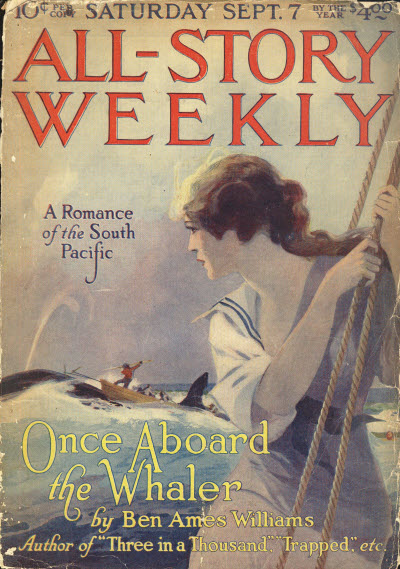

Using the masculine pen name “Francis Stevens,” from 1917–1923 Gertrude Barrows Bennett emerged as one of the first female writers to make a mark in fantasy writing and the nascent sf genre. HiLoBooks is pleased to serialize her 1918 story “Friend Island,” a proto-Forbidden Planet parable set in a woman-dominated 22nd century, for HILOBROW’s readers.

ALL INSTALLMENTS: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5.

It was upon the waterfront that I first met her, in one of the shabby little tea shops frequented by able sailoresses of the poorer type. The uptown, glittering resorts of the Lady Aviators’ Union were not for such as she.

Stern of feature, bronzed by wind and sun, her age could only be guessed, but I surmised at once that in her I beheld a survivor of the age of turbines and oil engines — a true sea-woman of that elder time when woman’s superiority to man had not been so long recognized. When, to emphasize their victory, women in all ranks were sterner than today’s need demands.

The spruce, smiling young maidens — engine-women and stokers of the great aluminum rollers, but despite their profession, very neat in gold-braided blue knickers and boleros — these looked askance at the hard-faced relic of a harsher day, as they passed in and out of the shop.

I, however, brazenly ignoring similar glances at myself, a mere male intruding on the haunts of the world’s ruling sex, drew a chair up beside the veteran. I ordered a full pot of tea, two cups and a plate of macaroons, and put on my most ingratiating air. Possibly my unconcealed admiration and interest were wiles not exercised in vain. Or the macaroons and tea, both excellent, may have loosened the old sea-woman’s tongue. At any rate, under cautious questioning, she had soon launched upon a series of reminiscences well beyond my hopes for color and variety.

“When I was a lass,” quoth the sea-woman, after a time, “there was none of this high-flying, gilt-edged, leather-stocking luxury about the sea. We sailed by the power of our oil and gasoline. If they failed on us, like as not ’twas the rubber ring and the rolling wave for ours.”

She referred to the archaic practice of placing a pneumatic affair called a life-preserver beneath the arms, in case of that dreaded disaster, now so unheard of, shipwreck.

“In them days there was still many a man bold enough to join our crews. And I’ve knowed cases,” she added condescendingly, “where just by the muscle and brawn of such men some poor sailor lass has reached shore alive that would have fed the sharks without ’em. Oh, I ain’t so down on men as you might think. It’s the spoiling of them that I don’t hold with. There’s too much preached nowadays that man is fit for nothing but to fetch and carry and do nurse-work in big child-homes. To my mind, a man who hasn’t the nerve of a woman ain’t fitted to father children, let alone raise ’em. But that’s not here nor there. My time’s past, and I know it, or I wouldn’t be setting here gossipin’ to you, my lad, over an empty teapot.”

I took the hint, and with our cups replenished, she bit thoughtfully into her fourteenth macaroon and continued.

“There’s one voyage I’m not likely to forget, though I live to be as old as Cap’n Mary Barnacle, of the Shouter. ’Twas aboard the old Shouter that this here voyage occurred, and it was her last and likewise Cap’n Mary’s. Cap’n Mary, she was then that decrepit, it seemed a mercy that she should go to her rest, and in good salt water at that.

“I remember the voyage for Cap’n Mary’s sake, but most I remember it because ’twas then that I come the nighest in my life to committin’ matrimony. For a man, the man had nerve; he was nearer bein’ companionable than any other man I ever seed; and if it hadn’t been for just one little event that showed up the — the mannishness of him, in a way I couldn’t abide, I reckon he’d be keepin’ house for me this minute.”

“We cleared from Frisco with a cargo of silkateen petticoats for Brisbane. Cap’n Mary was always strong on petticoats. Leather breeches or even half-skirts would ha’ paid far better, they being more in demand like, but Cap’n Mary was three-quarters owner, and says she, land women should buy petticoats, and if they didn’t it wouldn’t be the Lord’s fault nor hers for not providing ’em.

“We cleared on a fine day, which is an all sign — or was, then when the weather and the seas o’ God still counted in the trafficking of the humankind. Not two days out we met a whirling, mucking bouncer of a gale that well nigh threw the old Shouter a full point off her course in the first wallop. She was a stout craft, though. None of your featherweight, gas-lightened, paper-thin alloy shells, but toughened aluminum from stern to stern. Her turbine drove her through the combers at a forty-five knot clip, which named her a speedy craft for a freighter in them days.

“But this night, as we tore along through the creaming green billows, something unknown went ’way wrong down below.

RADIUM AGE PROTO-SF: “Radium Age” is Josh Glenn’s name for the nascent sf genre’s c. 1900–1935 era, a period which saw the discovery of radioactivity, i.e., the revelation that matter itself is constantly in movement — a fitting metaphor for the first decades of the 20th century, during which old scientific, religious, political, and social certainties were shattered. More info here.

FICTION & POETRY PUBLISHED HERE AT HILOBROW: Original novels, song-cycles, operas, stories, poems, and comics; plus rediscovered Radium Age proto-sf novels, stories, and poems; and more. Click here.

SERIALIZED BY HILOBOOKS: James Parker’s Cocky the Fox | Annalee Newitz’s “The Great Oxygen Race” | Matthew Battles’s “Imago” | & many more original and reissued novels and stories.