City on a Spill

By:

May 14, 2010

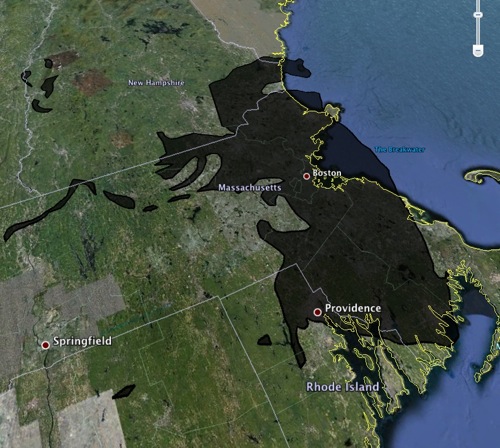

Late last month, as you’ve already heard — though, unless you live on the East Coast you haven’t given it much thought, just as we Bostonians never gave more than a few moments’ of horrified consideration to disasters in California, on the Gulf Coast, or halfway around the world — an explosion on the Deepwater Horizon offshore drilling rig caused oil to spill from the Pilgrim well, just off the coast of Massachusetts, a few thousand feet below sea level. Every day since then, as you can see for yourself by typing “Boston” into the Google Earth-powered Gulf Oil Spill Map, between 200,000 and 2 million gallons of crude oil a day (according to which estimate one chooses to believe) have gushed out of the Pilgrim well — and oozed inexorably landward.

Within a few days, the oil had reached New England’s once nearly pristine beaches, damaging (probably for a decade, or perhaps forever) the local fishing industry, and the habitats of hundreds of bird species. Currently, at its northernmost extent the spill has reached Portsmouth, N.H. It stretches southward from there along Rye Beach, Hampton Beach State Park, and Seabrook Dunes, then down along the Massachusetts coast through Salisbury and Newburyport to Boston (via Plum Island, Ipswich, Rockport, Gloucester, Manchester, Beverly, Marblehead, Swampscott, Lynn, Nahant, and Winthrop — quaint names we’ve heard repeated on the nightly news, like a winter school-closing mantra, for weeks now), thence down to Scituate via Quincy, Hingham, and Hull. Hundreds, maybe thousands of seabirds, fish, otters and seals, as well as some whales, float motionless, belly-up, Xs on the eyes, in a sort of foul chocolatey mousse churned up by the dwindling waves.

By April 29, wealthy private citizens in southern Maine and the town of Duxbury, Mass. (to whose rescue the semi-retired rocker Juliana Hatfield has rushed), had mobilized nearly 200 cleanup vessels — including skimmers, tugs, barges and recovery vessels. Over 100,000 feet (19 miles) of containment booms were deployed along the coast; by the next day, this nearly doubled to 180,000 feet (34 miles) of deployed booms. Hatfield helped fund Duxbury’s efforts by convincing Evan Dando and members of the Blake Babies, Del Fuegos, Gang Green, and Slapshot to join her in performing a moperock song celebrating both Duxbury Beach as a major, unspoiled, natural recreational asset, and Duxbury Bay’s active shellfish industry — thus managing to bridge the gap between the previously feuding fisherfolk, conservationists, and tourism industry professionals. The song, “Feelin’ Massachusetts’ Pain,” has been downloaded over 6,000 times, at $2.99 a pop. So far, thanks in no small part to the combined actions of Hatfield and the Bush and Clinton families, the oil spill has been prevented from spreading any farther north or south.

However, these efforts have had, shall we say, unexpected consequences. “Topography,” as the Boston Globe’s Alex Beam parroted, over and over again, “is destiny.” After having saturated Boston Harbor (and its islands), the oil spill — “spill” sounds too innocent, too gentle a word for the horror this phenomenon truly is — bumped up against the mainland.

Curious, we Bostonians flocked to beaches and docks, pointing and gossiping; I’m ashamed to say that some of us even picnicked within sight of the newly formed bitumen. Overnight, however, or so it seems in retrospect, the oily leviathan hunched its dark brown shoulders and o’erleapt our shores. Logan Airport was submerged inside of a 24-hour period. The low-lying coastal areas (a phrase I’ve heard so often, on the Weather Channel, without really thinking about it) were inundated first. Here in Boston, this meant the financial district, East Boston along Chelsea and Bennington Streets, and large swaths of Charlestown and South Boston.

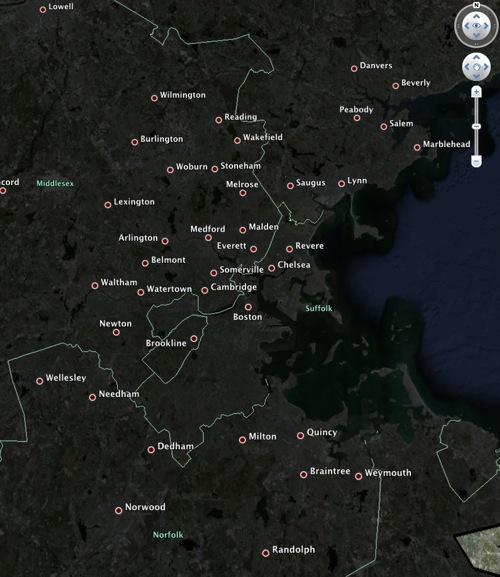

Soon enough, the oil had surged over the Charles River dam, and spilled into Cambridge and the Back Bay. The brown tide extended from Fenway to UMass-Boston in Dorchester. The Mayor, the Governor, Teresa Heinz Kerry, Ben Affleck, members of Aerosmith, Giselle, Jonathan Papelbon, and a woman dressed as (we assumed) Louisa May Alcott appeared on television, reassuring us that everything was OK — while in the same breath announcing that all power to the city would soon be cut off, lest a catastrophic fire get started. Meanwhile, the seaside towns of Revere, Winthrop, Quincy, Hull, and Hingham were evacuated; and once the oil spread up- and down-river, so were Somerville, Cambridge, Malden, Everett, Medford, Braintree, Weymouth, and Milton. Though I wasn’t there to witness the evacuations first-hand, I don’t believe cynical rumors to the effect that wealthier and lighter-skinned citizens were evacuated days ahead of everyone else; or, at least, I’d prefer not to believe them.

Downtown, we saw on television, before the signal was abruptly cut off, the scene was chaotic. Rescuers were scarcely able to move as the oil sucked the boots right off their feet. Trapped dogs and cats couldn’t be removed — so they had to be shot. The black sticky stuff filled cellars for blocks around. Salt water was sprayed on cobblestone streets, homes, and other buildings because fresh water just washed off the stuff. There was looting, rioting, public pot-smoking. Newscasters around the country got their tongues around the word “Massachusettsans.” Molasses Flood jokes wore thin. Still, there seemed no need to panic entirely; no need to join the general exodus.

One morning, Matthew Battles, my coeditor at HILOBROW, and I rode our bicycles from the neighborhood of Jamaica Plain into town — our destination Copley Square. A few blocks away from our destination, the sludge coating the streets and sidewalks to the depth of two or three inches made rolling progress impossible. I should note that we were the only souls venturing in an easterly direction. I should also note that we had to fend off the attacks of desperate men who wanted to commandeer our vehicles. Luckily, Matthew is not only a ferocious intellectual but a fearsome pugilist. I snapped a photo (below) of a hooligan whose nose was caved in by a one-two combination courtesy of the author of Library: An Unquiet History.

Carrying our bicycles above our heads we trudged with great difficulty along the submerged pavement of Dartmouth Street and entered the open door of the John Hancock building, which was all but deserted. The once-gleaming marble floors of this temple of finance were entirely blackened with oil. Ascending via emergency stairwell, after an hour of stiff climbing, we stepped out into the building’s observatory level. From it we could see the streets of Back Bay radiating in every direction, while below us the road was yellow from side to side with the tops of the motionless taxis. All, or nearly all, had their heads pointed outwards, showing how the terrified men and women of the city had at the last moment made a vain endeavor to rejoin their families in the suburbs or the country. Here and there amid the humbler cabs towered the great Hummer of some wealthy magnate, wedged hopelessly among the dammed stream of arrested traffic. Just beneath us there was such a one of great size and luxurious appearance, with its owner, a fat old man, leaning out, half his gross body through the window, and his podgy hand, gleaming with diamonds, outstretched as he urged his chauffeur to make a last effort to break through the press. A dozen MBTA buses towered up like islands in this flood, the passengers who crowded the roofs lying all huddled together and across each others’ laps like a child’s toys in a nursery.

Only one other picture shall I give of the scenes which we carried back in our memories from the dead city. It is a glimpse which we had of the interior of Trinity Church. Picking our way among the prostrate figures upon the steps, some of whom were dead, others covered head to toe in oil and barely alive, we pushed open the swing door and entered. It was a wonderful sight. The church was crammed from end to end with oily, kneeling figures in every posture of supplication and abasement. At this dreadful moment, brought suddenly face to face with the realities of life, those terrific realities which hang over us even while we follow the shadows, the terrified people had rushed into those old city churches which for generations had hardly ever held a congregation. There they huddled as close as they could kneel, many of them in their agitation still wearing their hats. A din of supplication and despair rattled the stained glass windows, which until today only tourists had ever seen.

That was a week ago, and matters have worsened. The neighborhoods of Dorchester, South Boston, the North End, Charlestown and East Boston were drowned in oil; then Allston and Brighton, Back Bay and most of downtown — except for the top of Beacon Hill, which remains above the oily waves for the moment. The southern and western neighborhoods of Roxbury, Jamaica Plain, Mission Hill, Roslindale, West Roxbury, Mattapan, Hyde Park — abandoned, but for a few stragglers like ourselves. Still constrained from befouling the Bush and Kennedy compounds in southern Maine, or the white sands of Duxbury, the oil slick now known as Boston’s Bane has progressed inward and onward. Along the border of New Hampshire and Massachusetts, the towns and cities of Amesbury, Haverhill, Lawrence and Lowell have been evacuated. The territory north of Boston and Cambridge — including Saugus, Peabody, Danvers, Andover, Tewksbury, Wilmington, Lexington, and Arlington — is all but derelict.

Trees and other plant life can survive being flooded by water; when flooded by oil, they begin to wither and shed leaves within hours. Boston’s Common, its Public Garden (whose greenhouse-grown plants were too garish for some people’s taste), the Commonwealth Avenue Mall lined with sweetgum, green ash, maple, linden, zelkova, Japanese pagoda, and its famous elms… blighted. The Back Bay Fens, the Riverway, Olmsted Park — once again, they’ve become a swamp, a lifeless one. The Arnold Arboretum — except for its hilltops — looks like nothing so much as Mordor.

To the west, the oil has choked off Watertown, Waltham, Wellesley, and Needham. To the south, Randolph, Norwood, and Dedham are kaput. However, by dint of a concerted effort involving booms, sorbents, chemical and biological agents, vacuums, and even bagels and croissants, the suburb of Brookline did hold fast for a few days longer than the once-glorious city which surrounded it on three sides. But the constant stream of refugees from Boston quickly made such defense efforts impossible. Newton’s town managers, meanwhile, had for years been secretively spending millions of tax dollars, not on schools or municipal workers’ salaries, but on the latest technology in spill containment — a wireless network that inflates bladders which employ disposable gas cylinders, or something like that. Details about this network are vague, because Newton was wiped out in fewer than twelve hours.

The oil spill now covers 2,500 square miles of earth and sea. Miraculously, or perhaps thanks to the near-daily rainstorms we’ve had this spring, the Flood has not yet been followed by Fire. But… that surely will not be the case for long. The fear-crazed summer residents of Cape Cod, Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket, and the Berkshires are considering a “planned burn” which — according to sane people — will turn into a holocaust, not only for any men and women remaining within the oil slick’s perimeter, but for every citizen of Massachusetts and New Hampshire, even in the unbefouled regions.

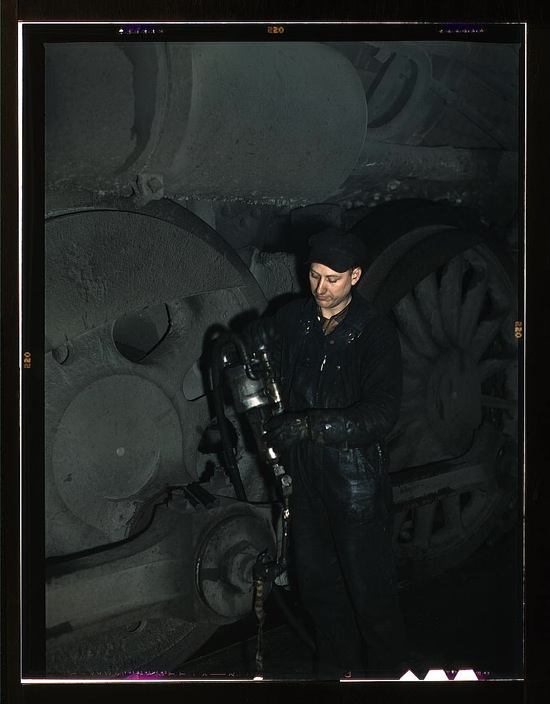

Along with our families and a select group of friends, Matthew and I have holed up in a redoubt atop a solar-powered liquor store here in West Roxbury. Supplies of goods that we’ve raided from Roche Bros. Supermarket are dwindling, it’s true, but downstairs there remain crates full of pretzels, cocktail olives, and Red Bull. (Fresh prose is in short supply, too, which is why I’ve borrowed two paragraphs from Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt when describing the scene in Boston, above.) The black sludge flows around us on every side, three feet deep. Abandoned cars, uprooted mailboxes, and corpses move past our redoubt. The fumes are intense; although the windows of our fortress are closed, a thin glistening film covers everything inside.

As the photo above demonstrates, our colleague, James, volunteered for the strenuous task of manually pumping oil out of the liquor store’s cellar. Night and day, we can all hear him down there — cursing, sobbing, then laughing wildly and singing “Rule, Britannia.” We think he’s actually enjoying himself, as these are much the same noises he used to make whenever we’d remind him that a deadline for an installment of his serialized novel-in-progress was approaching.

President Obama has called the spill “a potentially unprecedented environmental disaster,” but so far, no helicopters have arrived to bear us to safety. On NPR, experts are debating a long list of interlinked variables, including the weather, ocean currents, the properties of the oil involved and the success or failure of the frantic efforts to stanch the flow of oil and remediate its effects. Let them debate! The editors of HILOBROW will hold fast to our position, surviving on gin-and-tonics, pickled onions, and beef jerky, and posting updates via solar-powered WiFi, until the bitter end.

READ MORE essays by Joshua Glenn, originally published in: THE BAFFLER | BOSTON GLOBE IDEAS | BRAINIAC | CABINET | FEED | HERMENAUT | HILOBROW | HILOBROW: GENERATIONS | HILOBROW: RADIUM AGE SCIENCE FICTION | HILOBROW: SHOCKING BLOCKING | THE IDLER | IO9 | N+1 | NEW YORK TIMES BOOK REVIEW | SEMIONAUT | SLATE

Joshua Glenn’s books include UNBORED: THE ESSENTIAL FIELD GUIDE TO SERIOUS FUN (with Elizabeth Foy Larsen); and SIGNIFICANT OBJECTS: 100 EXTRAORDINARY STORIES ABOUT ORDINARY THINGS (with Rob Walker).